The Sinister Fun of Bradford Dillman

“By my reckoning, in over four decades I’ve been personally responsible for the demise of well over a thousand people. Heck, at Jonestown alone my Kool-Aid took out over nine hundred, and I’ve blown up the Queen Mary twice. Heroes are heroes. They pay the single greatest price of celebrity, the loss of privacy. This explains the army of bodyguards employed by some to keep the adoring multitudes at bay. Villains don’t have these problems. Me, I’ve never been bothered in a bar or boite. People can’t be sure I’m not carrying a knife or a gun.”

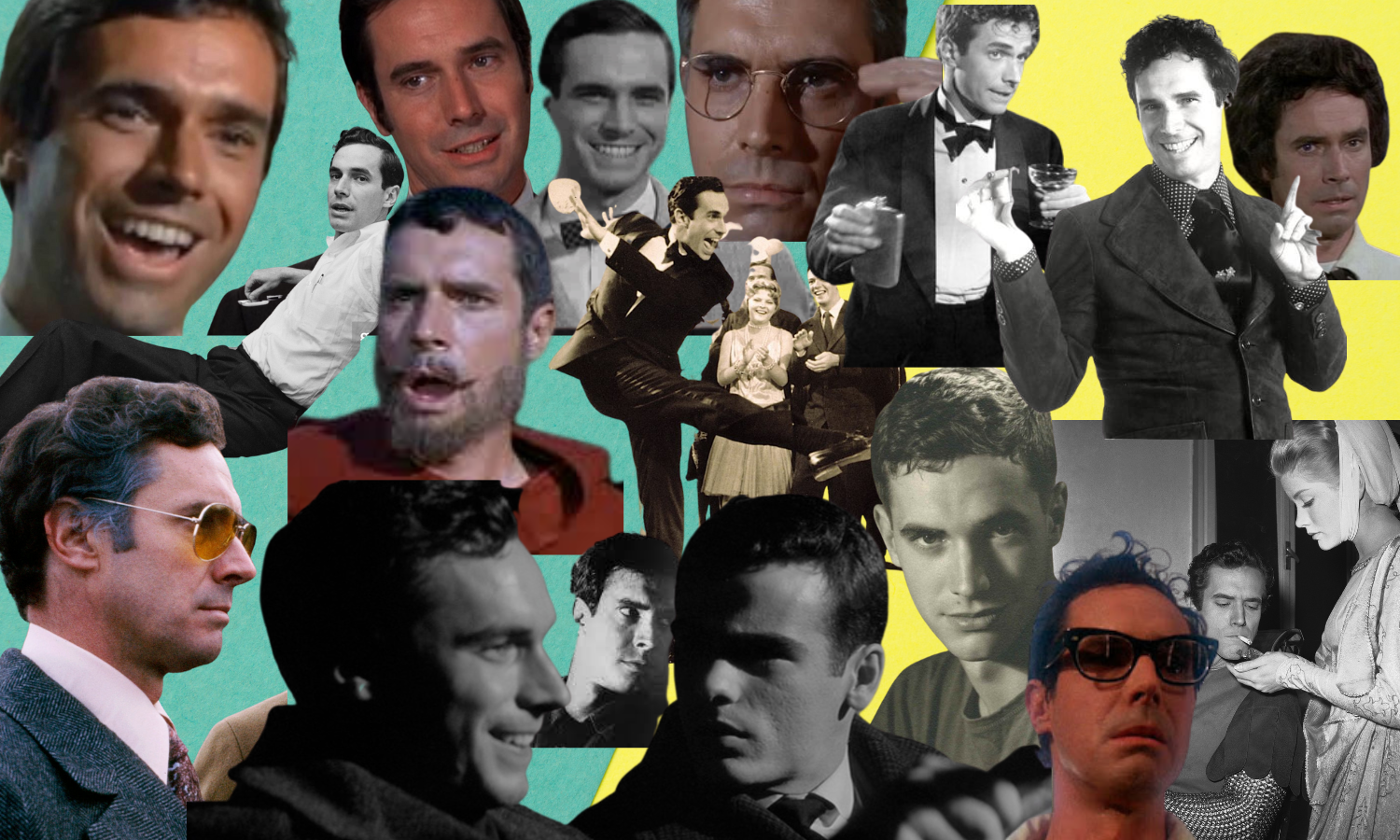

It is April, the sun is shining, and life is returning to some of our weary bones after what can only be described as a long, harsh winter of total discontent. In short, it’s Aries season, friends; and there is no better time to talk about charismatic villainous virtuoso Bradford Dillman (who would have turned 91 this April 14th). Bradford Dillman was an omnipresent actor in Hollywood for decades with a range that took him from The Actors Studio--debuting on stage with James Dean--and originating the role of Edmund Tyrone in the Broadway production of Long Day’s Journey Into Night to creature-feature horror and endless guest-starring roles attempting to kill the heroes in seemingly every 1960s and 1970s television program. He also kissed an ape in Escape From the Planet of the Apes.

Bradford Dillman is an heir to Peter Lorre and predecessor to Michael Shannon in the spectrum of actors giving us high-caliber sinister charm all mixed up with genuine emotional connection. He had the best evil smile in the business: a bent, slightly twisted smile that promised chaos--or at the very least some premeditated malice. His presence filled up all the empty spaces in every medium he appeared. A particular maximalist specialty of Dillman’s was the extended close-up on his face as it moved through dichotomous emotions--joy to rage; sadness to glee. He was acutely aware of movement in his face and body, but at the same time seemed to understand that he was supposed to provide an experience that was not quite human, more like human+. Why go out quietly, when you can go out screaming, howling, and/or cackling?

One of his early film roles was in Compulsion (1959), dir. Richard Fleischer, a fictionalized retelling of the Leopold and Loeb murder and trial. He played Artie Strauss (Loeb), a petulant 18-year-old rich boy who has never experienced a single consequence in his life and is convinced of his own superior intellect. He is as terrifying as he is charming, and his dominance over his (boy)friend as played by Dean Stockwell is the kind of performance that does not let you look away from it. Certainly not when he can be found carrying on an entire sinister conversation with a teddy bear. He shared the award for Best Actor at Cannes with co-stars Stockwell and Orson Welles (but not the teddy bear, which was a total snub). Compulsion is a film which is at times ethically dubious (for one, the murdered child is given almost zero consideration), but is at all times a work of performer-first filmmaking that builds a tremendous amount of tension, lets its actors run wild, and also contains a classic Welles’ fake nose (and fake eyebags?).

Dillman began as a method actor in important productions™, but since he and his wife Suzy Parker (supermodel; inspiration for Audrey in Funny Face) had a large family together, after she retired, he pivoted to being what he called a “Safeway actor”--anything to put food on the table. This is where he really shines: leaving a legacy of untrustworthy characters with intoxicating charm in every possible kind of film or television production. He was the man to go to for southern gothic werewolves or cult leaders or egotistical supervillains, and also sad dads or sweet dates-of-the-week for Mary Richards, or if you needed someone to play the nephew getting murdered by Uncle Ray Milland in an episode of Columbo. (My kingdom, my kingdom for an episode of Columbo with Bradford Dillman playing the murderer! Come on, Robert Culp and Jack Cassidy--stop being so greedy!)

One such unassuming production that got injected with Dillman was Jigsaw (1968), dir. James Goldstone. Jigsaw is a drug-trip murder mystery of uncommon chaos. (One wonders if even the film stock itself was laced with LSD?) It is also total fun, and perhaps even the platonic ideal of a sinister fun Bradford Dillman performance. He plays a repressed, emotionless scientist who wakes up with amnesia, blood on his hands, and in a room with a dead body. Suffice to say, the plot does later require him to trip on acid for ten minutes so he can remember (that’s how it works). The film was shot as a TV movie, but the content was too hot, so it got a theatrical release instead. Bradford Dillman has a great time, and the film plays up his unmatched ability to depict mania. Aside from the unfortunate use of a gruesome murder of a woman as essentially a plot mcguffin, this film offers perfect 1968 colorful+chaotic vibes.

That same year saw a theatrical release of another American television production with The Helicopter Spies (1968), dir. Boris Sagal, a two-part episode of Man From U.N.C.L.E. edited together as a single film for an international theatrical release. It contains an astonishingly fun performance from Dillman as the leader of a cult called The Third Way. Everyone in the cult (aside from him) is forced to dye their hair white blonde to match The High Priestess, while he wears an entirely white outfit (suit, shirt, shoes). Cult members greet each other by saying, “Keep the faith!” while offering a thumbs up. Naturally, he has plans to take over the world, charms absolutely everyone into believing him (including our two heroes), and goes on scamming. Because it is Dillman, we are never quite sure whether he is maliciously scamming for power and using the cult as a means; or whether he is maliciously scamming for power while actually believing in the cult. Delicious!

It is that level of morally unstable character (to borrow a line from The Naked Spur) that makes even supporting performances in films like Five Desperate Women (1971), dir. Ted Post, so much fun. The titular women are Joan Hackett, Stefanie Powers, Anjanette Comer, Denise Nicholas, and Julie Sommars. They are college BFFS reuniting on a private island cabin after five years--and they are a "mess" (some of them don’t even have husbands or babies yikes!). The chemistry between the women is genuinely perfect, and is a great intersection of heartfelt and camp. What we know, but the women do not, is that a murderous man is currently loose in the area. Naturally, our suspicion falls on Bradford Dillman as the boat captain who ferries them over to the island. He is a real weirdo and alienates them all almost immediately by explaining nutrition and how they clearly do not understand health like he understands it. Bradford Dillman keeps us dancing the whole time on the power of his sinister reputation alone.

This reputation for crafting exceptionally twisted...but fun characters (imagine I am saying that in a Sullivan’s Travels-like “with a little sex in it” cadence) kept him employed for decades. One of his final films was the Roger Corman-produced Lords of the Deep (1989), dir. Mary Ann Fisher. Honestly, this film is weird and freaky--and worth it for the wild camera work and special effects alone. It opens with a title card letting us know the year is 2020, and “Man has used up and destroyed most of Earth’s resources.” *gulp* Bradford Dillman is the good company man who commands a huge corporation’s experimental underwater habitat. He is a sinister capitalist who will see everyone dead before losing a drop of profits. He slithers around saying things like, “Are you imPLYING that I would endanger the lives of MY crew?” and “We used to have a thing called an Ozone, Jack. Remember? ... You idiot.” It had been thirty years since Compulsion, and he had not lost an ounce of his ability to terrify and charm in equal measures.

These five films I have picked practically at random, and they do not even begin to touch on the levels of delight to be had in Bradford Dillman’s 40-year, 142-credit film and television career. (These five are all available on streaming, however. I would especially give a look toward searching these titles on YouTube, ahem.) You can choose any one of his 142 performances and find something to shock, awe, and/or entertain you.

And, he certainly did not always play the bad guy (not even in all of these five films), but just as his villainy was multifaceted--his goodness was complicated. Suspicious, dark, twisted and bent like his famous smile. The man knew how to show us a good time.

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 04/05/2021.

-Meg

An Ode to Sandra Dee

Let me paint a picture for you: It’s 2008, and I am 14-years-old, and newly attending a local homeschool co-op that meets every Monday in a church that’s forty minutes from my home. A homeschool co-op is an educational construct in which a bunch of homeschool moms (and it’s always moms) create their own insular school system and then teach the children of the other moms so that the art moms can just focus on art, the theology moms theology, the founding fathers moms the founding fathers, and the one mom who is really good at math tries to explain calculus to a bunch of teens who had taught themselves how to add and subtract and multiply and divide. There is no science mom.

This is as close to a classroom or school setting as I had ever been at the time, and I was delighted by the concept of school supplies at last (oh, how I had coveted those overflowing bins at Target), and naturally, immediately decorated my class folders with photos printed out at the public library. I had a James Dean folder, a Grace Kelly folder, an Audrey Hepburn folder, an Ingrid Bergman folder, and a Sandra Dee folder.

On that first Monday, the teacher-mom for the Sandra Dee folder class (it was something like American Citizenship 101) asked me who was on my folder. I said with enthusiasm, “It’s Sandra Dee!” This was a few months before I started my film blog, and I was eager for any outlet to talk. In a move that prepared me for every internet-splainer to come, teacher-mom responded, “No that isn’t Sandra Dee. Sandra Dee is a character in Grease. ‘Look at me, I’m Sandra Dee…’” (She did not finish the lyric, which clearly was a spectre from her heathen youth, as Grease was not co-op approved.) I was torn between knowing that adults should never be corrected, and also by knowing that, well, it was Sandra Dee on my folder. I went with a mumbled, “This is Sandra Dee, the actress.” Teacher-mom said, “No, you must be confused.”

And that was that. I saw no path to victory, but internal fuming, and going home and turning on my library’s DVD of Gidget (1959, dir. Paul Wendkos) that was on semi-permanent loan to me, and watching Sandra Dee prove all her doubters wrong.

Sandra Dee on-screen always proved her doubters wrong. And it was exactly what I needed. She remains one of my favorite people to return to on film: a friendly cinema companion. Her presence carries a quality, a tangibility, a gravitas that has never been allowed to be attached to her name by critics or public opinion. Lucky then that Sandra Dee did not need permission to be indelible.

She is unmistakable onscreen and entirely irreplaceable. The Gidget sequels are enough to tell you that. I mean, look, I am one of the bigger supporters of Gidget Goes Hawaiian, and yes, I did once tell Carl Reiner that Gidget Goes Hawaiian was a great film to which he responded, “No.” But, Deborah Walley as Gidget is just filling space. (And we do not talk about nor acknowledge Gidget Goes to Rome.)

Sandra Dee’s Gidget is alive, so fully alive. She is energy and enthusiasm and vulnerability and confusion and angst and elasticity. Her triumph in learning to surf feels like an earned triumph and the joy is palpable, and equally her scenes late in the film with Cliff Robertson’s predatory Big Kahuna are genuinely distressing because of her performance and her efforts. While Sandra Dee’s work is often tossed away as light-weight and sterile based on some historical collective false memory, her performance in Gidget should really be considered a direct predecessor to Elsie Fisher’s recent acclaimed work in Eighth Grade (2018). Sandra Dee gave us a realistic vulnerable yet determined teen girl who absolutely triumphs (with the loving support of her teen girl BFF) and teen girl me said, “You love to see it! Can you please ditch Moondoggie though? He is a drag.”

Sandra Dee’s known public image today and her original popularity was definitely predicated on her fulfilling some sort of white wholesome teen girl ideal for a 1950s American audience, but conversely her characters are boundary-crossing troublesome girls and young women. A defining characteristic across so many of her roles is a refusal to conform--in small ways and big.

In The Reluctant Debutante (1958, dir. Vincente Minnelli), only her second film, in the midst of swirling mania, she is the cool one--observing the hysteria with bemusement and maintaining her personal sense of self throughout. She assuredly partners with Kay Kendall and Angela Lansbury with a level of confidence that astounds. Her comic timing is already excellent here, and so is her ability to work ensemble. Her most perfect ensemble obviously being Come September (1961, dir. Robert Mulligan), a film that is surely one of the reasons cinema exists as a visual art medium. Sandra Dee and her tangibility are vital. With all due respect to the blonde youth actresses of the 1960s (I love many of them), how many of them would have the precise energy to match so comfortably on-scene with peak powers Gina Lollobrigida and Rock Hudson? There is a scene in which she psychoanalyzes Hudson that is masterfully funny. Her scenes with Bobby Darin are equal parts tentative and confident; sweet and confused. And with Gina Lollobrigida, she is sincere and kind with immediate rapport. There is no danger of fading into one-half of the obligatory forgettable youth B-couple of the movie--even in the presence of the dazzling Lollobrigida and Hudson.

The other two films in the Sandra Dee-Bobby Darin trilogy are also particular fun--with outlandish plots. In If A Man Answers (1962, dir. Henry Levin), she decides to change Darin’s behaviour with a dog training manual, and in That Funny Feeling (1965, dir. Richard Thorpe) via some classic mistaken identity she convinces him his apartment is actually her apartment. She is the firm center, sweetly spinning Darin and the rest of the film around in circles of befuddlement while she decides what she wants and when.

This aura of self-autonomy made Sandra Dee one of my figures of aspiration as a girl. In her characters, she lets the audience see the process of doubt and vulnerability while also making the decision. Her way of speaking is memorable: sometimes halting with clipped sentences and sometimes too many words spoken too quickly, but she really does always keep speaking.

Her openness onscreen is definitely why young me always preferred to rewatch her comedies rather than her melodramas--the vulnerability was too real. I have a very vivid memory of watching A Summer Place (1959, dir. Delmer Daves) as a 12-year-old hoping it would be another Gidget and my dawning horror as the melodrama played out. Sandra Dee played yearning angst and vulnerability so acutely--it hurt me. I must confess I have never rewatched the film, and to this day, hearing that wistful theme tune is enough to re-traumatize me.

Sandra Dee played Lana Turner’s daughter twice, most famously in peak melodrama Imitation of Life (1959, dir. Douglas Sirk), and again in the seedy Portrait in Black (1960, dir. Michael Gordon). Dee and Turner match up perfectly, both so adept at playing girls and women grasping for self-autonomy and self-preservation in a world that has no intention of making it easy. I wonder if Sandra Dee’s career had continued past her 20s if she would have found herself in Lana Turner-like roles?

Instead her final film appearance came in 1970, at the age of 28, in The Dunwich Horror (dir. Daniel Haller). She plays opposite another former teen-actor-with-substance Dean Stockwell in a freaky tale of the occult and monsters that feels subtly template-like for many films that followed. Her soft vulnerability amidst the chaotic production stuns. In Sandra Dee’s hands, Nancy is not a stupid, gullible woman led easily into danger, but an open and empathetic woman trying to balance danger against desire: a navigation that is true in every day life even when your job and studies do not include the possibility of your body becoming a gateway vessel for demons.

Oh Sandra Dee, I wanted to compose an ode to you, but I do not have all the words I need.

Oh Sandra Dee, you’re not a pastiche of people’s false memories, a relic from a plastic era, or the line from a song-- instead, resolve and humor, humanity and kindness, and an absolute knowledge of the ridiculousness of life--it all showed up on screen and bolstered a girl who desperately needed to see another girl triumph. 💖

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 09/05/2021.

-Meg

The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown (1957): we need to talk about Jane Russell in menswear

The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown has everything…

The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown // dir. Norman Taurog // United States

The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown has everything: Jane Russell in a cheap blonde wig, Ralph Meeker kidnapping someone, Keenan Wynn third-wheeling, Hollywood insider shenanigans, action intrigue, cops getting knocked out with ash trays, Una Merkel wise-cracking, eggnog-induced drunken antics, Adolphe Menjou gliding around like it’s 1937, and of course, confusing and troubling moral ethics baked right into the script!

Yes, this film is about a movie star falling in love with her violent and frightening kidnapper. And, also yes, Jane Russell is a pure powerhouse of charisma and Ralph Meeker is a rare and perfect male energy match for her.

Look, I love The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown. I need to enumerate every reason.

Let me give you the short pitch: It’s Noirvember (shout-out to founder Marya E. Gates), so why not watch Jane Russell swagger in a Double Indemnity-style wig while tussling with Ralph Meeker who is being violent, anti-social, and cynical---BUT IT IS A ROMANTIC COMEDY!

The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown defies explanation.

On one hand, it feels low-budget and takes place mostly in one location that could double for a set from a television show. On the other hand, it is Jane Russell, Ralph Meeker, and Keenan Wynn each at peak powers doing a cleverly-paced three-hander.

Jane Russell produced this film (her fourth film with her production company Russ-Field), and plays the lead: Laurel Stevens, a glamorous movie star frustrated by her limiting sex symbol status. Russell counted this as her favorite film (alongside Gentlemen Prefer Blondes), and it feels very attuned to her. Laurel Stevens knows the misogynistic game in Hollywood, and she is happy to name it, making it clear in diatribe against studio executives she shares with her assistant (Una Merkel !!!) right at the top of the film:

“Oh, sure, when they were pushing me around, it was just good business. But let me start dishing out a little action, and I’m tough and temperamental.”

She continues, speaking of desire for personal autonomy, “I’m just a simple business girl. I sell a funny, phoney commodity called sex, and if the customers are hungry enough to buy it, I run my factory in my own way.”

She heads out the door of her home to a waiting car taking her to the premiere of her new film, The Kidnapped Bride. Instead of chauffeurs, it’s Ralph Meeker and Keenan Wynn--and they literally kidnap her to hold her for ransom.

Laurel Stevens is in no way frightened of her kidnappers, and is instead horrified that the press and movie-going public are going to think this is a publicity stunt and turn against her. Her agent and film producer (Adolphe Menjou !!!) are worried about this too, so they are unwilling to report her missing. The kidnappers have her holed up in a Malibu beach house (Kiss Me Deadly crossover potential), but she is not going to make it easy.

Shenanigans ensue.

Jane Russell’s work here is supremely confident. She truly feels like she’s two feet taller than everyone else. She doesn’t glide through the film. She smashes her way through the film. She is funny, cynical, powerful, and so very present.

The wig comes off (spoiler alert!), Ralph Meeker’s Mike (not Mike Hammer, but god can you imagine!) becomes fixated with what that wig means in terms of authenticity. He apparently has some childhood trauma related to a candy store that lied to him about bubble gum and anyway that is why he hates phonies and is angry about a wig? Listen, I love it.

Laurel: "Look, what have you got against me, anyway?"

Mike: “I don't like phonies. When I was a kid, there was a little weasel that ran a candy store on Coney Island. Sundays and holidays, he put a big sign in the window: "Free Bubblegum." Only the store was always closed. I never got enough of hating that guy.”

This film was not financially successful, and the critics had mixed-feelings. In particular, critics felt very meh about Meeker’s rough and gruff performance, and wanted someone a little more classically funny. But, genuinely, his decision to play this ostensibly light comedy character as a smirking, brutalist cynic barely containing his ever-present rage is genius.

If he was less terrifying, I might feel a little better about the fictional characters’ happily-ever-after actually working out (LAUREL, RUN!), but as it is, Russell and Meeker play off each other in a perfect sync. In their mouths, rote 1950s studio dialogue is given life that it probably doesn’t deserve, and I am left quietly cackling to myself.

And, oh Keenan Wynn. What a genuine great. I have extolled his virtues here before, but really I always need people to really grasp how good he was as an actor. His Dandy here is the understanding sweetie of the kidnapping duo and the third wheel of a dangerously toxic long weekend in Malibu. He comes off as being just a little in love with both Laurel and Mike, and both of them continuously and selfishly use him to their own ends. For an intended comedic side-kick in studio comedy, he gives a surprisingly tender and emotionally-aware performance. Dandy is the unexpected little beating heart to the movie (and also my personal cinema avatar, but let’s not get into that right now).

I LOVE THIS WEIRD MOVIE.

Genuinely, I guess I can see why it was not popular in its contemporary release, because it is ever-so-slightly unhinged, but also please follow me on this journey to bring about The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown renaissance, so I can finally get a home video release.

I mean, Jane Russell, because of plot machinations, essentially only is seen in repurposed menswear throughout the film, and the power that has is indescribable.

Ralph Meeker only wears soft, comfy sweaters (SWEATER WEATHER) while ragefully smoking a pipe, and there is a quiet power to that as well.

It makes absolutely no sense that this film is in black and white instead of glorious technicolor (literally do not name your film after a color and then not have color), but also it oddly makes the most sense because, again, this movie is not a light studio comedy. It’s a film about Hollywood and all its darkness.

It is also a film in which Jane Russell gets drunk on eggnog and also in which she stone-cold sober knocks out a cop and steals his car!

I am literally lightly cackling to myself--out loud--alone in my apartment right now remembering how much this film delights me. I think those of us who love cinema have a myriad of reasons why we do. I know I certainly love cinema for the transcendent moments of beauty, for its ability to immerse us into another life, for the social connections, for the community it creates, for the visually stunning images. I also love cinema for sometimes being absolutely ridiculous. Film is a collaborative medium in its very nature, and sometimes, you take a step back in your mind, and survey a work like this and realize how many people contributed to the glorious absurdity of it.

What is The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown if not a product of dozens and dozens of skilled creators who all thought to themselves, “yeah, this will work”?

It does work. It is a great time. It is also a little bit about Stockholm Syndrome. But, mostly, it is about Jane Russell being tall and wearing hats and having absolute control over her image for one glorious film.

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 11/07/2021.

-Meg

A Robert Donat Monologue For Every Wistful Occasion

Robert Donat is the monologue god. No one can touch him when it comes to staring plaintively off into the middle distance–the weight of eternity on his shoulders. The understanding of the fragility of human life fueling his insistence to go on–to keep on living.

Robert Donat is the monologue god. No one can touch him when it comes to staring plaintively off into the middle distance–the weight of eternity on his shoulders. The understanding of the fragility of human life fueling his insistence to go on–to keep on living.

Here I have compiled a few helpful Donat monologues to help us understand our own feelings and ultimately our own humanity and the purpose of our existence (not all of them are actual monologues strictly speaking please do not @ me).

For when you’re burnt out at work, and really in that surviving not thriving mode, listen to Robert Donat in the clip in the header via Vacation from Marriage (1945) tell you about the groove being comfortable, but yikes so is the grave:

For those times when you’re isolating because of a COVID scare, or just trying to make it through the darkest days of winter, check out Robert Donat having a literal freakout in Knight Without Armour (1937):

When the call of the void is calling you, nothing for it but Donat in The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933):

When it is time to eat the idle rich, we channel Robert Donat’s impassioned impromptu campaign speech in The 39 Steps (1935). Richard Hannay is my first and truest love and inspiration:

For those times you must hold equal, yet seemingly opposing truths together in balanced tension, because life is not simple but it is always true that human beings do matter and war, violence, and empire is always senseless, Mr. Chips announcing the deaths of two people he held dear in Goodbye, Mr Chips (1939):

For when you watch a sublime film and are overcome by your sheer love for the very medium of cinema and all that it gives us each and every day, here comes Robert Donat in The Magic Box (1951) literally sobbing about it to an awestruck Laurence Olivier who will never understand like Donat does the power of film because Donat won the Best Actor Oscar in 1939 instead of Olivier and that’s because Donat feels and the world feels with him:

Robert Donat on film understood how to express loneliness and yearning in such formidable delicacy. Such a stunning presence, and such a beautiful voice to express the fears and hopes of humanity. I will never grow tire of his earnest efforts, and I will watch his films and cry thank you very much.

[Insert Donat Magic Box monologue but it is me weeping about Donat cinema monologues]

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 03/02/2022.

-Meg

QUIZ: Who is Your Classic Film Character Summer Fling?

I love a personality quiz. When I was a kid, I lived for the quizzes in my American Girl magazines. Which kind of dog are you? What famous female athlete are you? What kind of cheese are you? It did not matter. I wanted to answer the questions, and then proudly know that I was unique. I was not like other girls. I was a border collie (as true now as it was then).

We’ve reached the highpoint of summer. Heat domes all over the place. Honestly, too much sun, if you ask me. (No thank you, sun. I’m good.) The time is right to kick back with a cold beverage and take my little quiz and learn who your perfect classic film summer fling is going to be (oooooooh)....from the 7 options I am giving you (to be frank, they were the ones top o’ my mind, and all delightful characters).

Here is how it’s going to work: as you go, write down the number of your answer to each question, and at the end, add up your answers to find your perfect partner for this season. Aka if you answer mostly 1s, then 1 is your summer fling or mostly 5s, etc. I have included an answer key at the bottom. If you’re more love ‘em and leave ‘em, then consider a ranked choice system to come up with your top three beaus!

QUESTION ONE: It’s summertime! It’s time to take a holiday. You’ve been working hard, and you deserve a break. Your ideal vacation is______.

1. Kicking it back in an Italian villa. You like to spend your time in luxury, and you are not looking to do much else but chill out. Maybe a vespa ride around the countryside or a dance here or there, but mostly you like lounging out in the sun.

2. Taking a trip on a sailboat. You don’t even mind working as crew–you just want to get out there on the waves and experience that freedom that only the open ocean can provide.

3. Staycation! You live in the big city, and you enjoy your life. There is always something new to do, or explore. You do not need to go anywhere to relax.

4. Nothing planned. You are all about spontaneity. You pick a new place to visit and just go exploring. You are sure you will find an adventure.

5. Not a family vacation! You are trying to get away from your family, not spend more time with them.

6. On a train. You love to travel by train and stop off along the way throughout the countryside and little towns. Hiking, running, scrambling over rocks–anything that gets you outside and active.

7. VACATION? Who has time for vacation? You do not. You have things to accomplish, and nothing else matters.

QUESTIONS TWO: Ahh food! There are few things better in the world than sitting down to eat your perfect meal. The food you crave most is____.

1. Italian food paired with a perfect wine.

2. Well, food does not really satisfy you in itself–but you love an experience. You have always wanted to have a real picnic!

3. This little Japanese restaurant down the street that has an incredible, authentic menu.

4. Whatever food is right in front of you! You love to feast and feast and feast. You keep snacks next to your bed–just in case–and a jar of pickles is never unwelcome.

5. A home-cooked meal from someone you love. It does not matter what it is, it is worth all your money.

6. Simple fare. Anything that is easy to find along the road. You love a sandwich.

7. FOOD? Who has time for food? You do not. You have things to accomplish, and nothing else matters.

QUESTION THREE: What is the most played song on your playlist?

1. "Mambo Italiano" by Rosemary Clooney

2. "bad guy" by Billie Eilish

3. Anything new and avant-garde.

4. "I Love It" by Icona Pop

5. "I’m On Fire" by Bruce Springsteen

6. "Run for Your Life" by The Beatles

7. You don’t listen to much music, but you love to sing. People always know you’re around when they can hear you singing.

QUESTION FOUR: What was your favorite game to play when you were a kid?

1. Musical Chairs. You love group games, dancing, and making sure everyone is having a good time.

2. Wink Murder. No one ever guessed it was you even though you drew the murderer card every time.

3. Anything you could make a bet on. You knew how to win and make money from a young age.

4. Games with rules are boring. And don’t even get you started on board games: you get tired of them easily and tend to flip the board!

5. Spin the Bottle. hehe.

6. Hide and Seek. You were always the best.

7. Clue. You are clever, patient, and determined. You always found the murderer.

QUESTION FIVE: What is your favorite animal?

1. Definitely not parakeets.

2. Sharks. You saw a group of sharks attack an injured shark once and have never forgotten the spectacular sight.

3. Anything wild and free. No domesticated cats.

4. Honey Bees. You're here for a good time, not a long time.

5. Geese. When you've found the right partner, you're in it for life.

6. Foxes. You love their cozy little hidden dens.

7. A lone wolf. You admire their ability to track and hunt.

QUESTION SIX: What is your greatest fear?

1. Not being taken seriously.

2. Not getting to see the sunrise one last time.

3. Getting trapped.

4. Being bored and/or running out of snacks.

5. Being disrespected.

6. Someone telling lies about you.

7. Not fulfilling your purpose in life.

QUESTION SEVEN: You’ve been shipwrecked and stranded on a desert island, but you managed to carry two items with you from the sinking boat that you knew you needed to survive. Those items are_____.

1. A portable two-way radio and signal flags.

2. A knife and a gun.

3. An inflatable lifeboat and a compass.

4. A pair of scissors and a large jar of pickles.

5. Flint and a first aid kit.

6. A tarp for shelter and a machete to cut open coconuts. I guess you live here now.

7. Does it matter? You’ll figure a way out.

QUESTION EIGHT: Your favorite way to interact with other people online is___.

1. You are on every app at all times and have literally thousands of devoted fans, errr, friends.

2. Twitter. It is both the source of your sickness and its only antidote.

3. LinkedIn. Professional use only. The real life is happening offline.

4. Tumblr, baby! You know how to curate!

5. Exchanging numbers with your Tinder matches and then texting for 12 hours straight.

6. Signal messaging via burner phones only please.

7. You do not really have time for this, but okay, you sometimes post cryptic yet wistful poetry on your old LiveJournal. It reminds you of a different time when you were younger and happier.

ANSWER KEY

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 1's....

Your summer fling is Lisa Fellini as played by Gina Lollobrigida in Come September (1961). You are fun and flirty and a great communicator. You love to socialize and everyone sees you as the life of the party. You know what you want and you have great boundaries. Enjoy riding that vespa around the Italian Coast with the most beautiful woman in Italy. She demands respect, honesty, and commitment–so do not mess this up!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 2's....

Your summer fling is Elsa Bannister as played by Rita Hayworth in The Lady from Shanghai (1947). The people that know you would say that you are intense. But they also cannot look away from your allure. You are mesmerizing and totally misunderstood (but also a little evil, sorry!). Your cynicism is a good match for Elsa, and you both are not expecting more than you can offer. You and Elsa are either going to have a great summer or immediately break up. Hard to say, but it will be a wild ride while it lasts! Good luck!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 3's....

Your summer fling is Jack Parks as played by Sidney Poitier in For Love of Ivy (1968). You are independent and reliable, and undeniably cool. You know all the best places to eat and hang out. You live in the city and you love it at every hour–day and night. Just like Jack, your community is important to you, and you work hard to make sure the people around you are taken care of each day. You and Jack are both not looking to settle down…or are you?

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 4's....

Your summer fling is Marie I and Marie II as played by Jitka Cerhová and Ivana Karbanová in Daisies (1966). You are chaotic, unpredictable, and totally vibrant! You are not big on plans and love to take each day as it comes. You deeply understand the futility of society and choose your own path of joyful nihilism. You absolutely do not like to be left alone for any amount of time, and neither do the Maries! Get ready for a summer of feasting, snacking, and decadent food fights. Grab a baguette and jump in–the milk bath temp is wonderful!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 5's....

Your summer fling is Clara Varner and Ben Quick as played by Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman in The Long, Hot Summer (1958). You’re intense and focused, but also a hopeless romantic. You have high standards and a great deal of self respect. You are not going to settle for anything less than the best, but once you have your sights on the best–watch out! Clara and Ben saw you from across the bar and liked your vibe…

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 6's....

Your summer fling is Richard Hannay as played by Robert Donat in The 39 Steps (1934). Frankly, you have a lot going on. You are a busy person always on the go, go, go. A natural traveler, you feel comfortable in every situation and circumstance and you make friends easily. There is nothing quite like a scramble over the rocks or a walk through the moors, and you do well outdoors. Although incredibly likable and adaptable, you and Richard both tend to hide your true selves and have trouble trusting other people. This may make your relationship a short-lived one, but if you can find a way to let each other in–maybe you go the distance together!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 7's....

Your summer fling is Tetsuya "Phoenix Tetsu" Hondo as played by Tetsuya Watari in Tokyo Drifter (1966). You do not have time for a relationship, as you are all-consumingly focused on your life’s mission. Everything else fades in the background. You must complete your task; you must fulfill your purpose. You are lonely, and although you might sometimes seem like a hard-hearted island of a person, you are actually very tender and gentle in your soul. There is a real softness about you, and if you could just be free of your work–free of your drive–you know that you would choose a very different life. Tetsu is on a parallel path as you, and together maybe you finally accomplish that

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 08/11/2022.

-Meg

“I am not loveable”: Laurence Harvey and the performance of self-presentation

“Someone once asked me, ‘Why is it so many people hate you?’ and I said, ‘Do they? How super!’ I'm really quite pleased about it.”

“Someone once asked me, ‘Why is it so many people hate you?’ and I said, ‘Do they? How super! I’m really quite pleased about it.’”

Laurence Harvey fascinates me as an actor. As someone who had a relatively low-impact career (and certainly a short life, dying age 45), his acting continues to inspire a remarkable level of divisive responses among film people™. I have never quite been able to figure out exactly why, but it does seem rather instinctual. And, I am not usually one to wade into film people™ fights without a firm ground. (You can find teenage me timidly acknowledging, “people either love him or hate him,” in a review of The Ceremony.)

Nevertheless, my first instinctual response to Laurence Harvey was absolute delight. I was maybe 11 or 12, and I saw his episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. It has stayed firmly planted in my memory from the pure audaciousness. It is quite gruesome and unrepentant. Harvey plays the titular chicken farmer named Arthur, a charming but basically anti-social figure. He opens by telling the audience, smiling, “I am a murderer,” and then narrates his story. He murders his fiancé, disposes of her body in the chicken feed, raises chickens on that feed, and eventually sends some gift chickens to an investigating cop. The cop is so enamored with the taste, he asks for a list of feed ingredients. Arthur obliges, turning to the camera to state smoothly, “All but one. I left out that one special ingredient that really made it.” There is no justice and there are no consequences. (Hitchcock does offer a cheeky closing statement about the chickens growing to an enormous size and then probably killing and eating Arthur.)

I was transfixed. His character, and the story, were certainly misogynistic (a common characteristic across many Harvey roles), but there was something that intrigued me: the utterly manufactured façade of a self-image he projected.

Around the same time, I unintentionally saw his episode of Columbo (released in 1973, just a few months before his death): he played an emotionless chess freak murderer. In this, his character is once again set apart from natural and expected human warmth and emotion. I said, “Well, well, well. Tell me more.” (Let us not delve into my childhood psyche nurtured on too much Hitchcock and Columbo, and the Beatrix Potter story in which Tom Kitten is almost turned into a roly-poly pudding by giant rats.)

From then on, I kept an eye out for Laurence Harvey (carefully learning, with a couple missteps, to differentiate his name in a cast list from that of the viscerally terrifying and despicable presence of Lawrence Tierney). What he had onscreen, I could never quite articulate in my blogging youth, but I understood it and was drawn to it.

His screen persona was always openly enigmatic. He never tried to hide the fact that he was hiding—hiding his true self; his true feelings.

I have always connected his depiction of masculinity with that of Steve McQueen actually. McQueen is held up in popular memory as some icon of masculinity in the same limiting and distorted fashion that Marilyn Monroe is held up as an icon of femininity. Of course, they were actually both much more—and infinitely more complex—than the shallow containment allows (more on the glorious Monroe another time).

McQueen’s depiction of masculinity is far more complicated (and interesting) than his popular legacy would suggest, and far more aligned with Harvey than immediately obvious. Just as Harvey’s characters were often steeped in misogyny, McQueen’s were often violent—uncomfortably so. But also fractured. As if the confidence to live and express himself only worked in a narrow, tightly-controlled sphere, and he better not say too much or change his ways too much—or everything might disintegrate.

McQueen’s characters distracted us from their internalized self-doubt with an erected façade of coolness. He looked cool, and did performatively cool things, and never said too much—so how could we say he was anything but supremely confident himself? The cracks showed through though. (And his own pal James Garner called him an “insecure poseur” in real life, which is blatant Aries v. Aries violence but I’ll allow it.)

Why have I taken a detour through McQueen to talk about Harvey? I think they both spent their short careers depicting unsafe men: men who correspondingly never felt safe themselves to just be. McQueen covered his characters’ fractures with uncannily good film choices and an ability to project coolness. Harvey never even tried to play his characters as anything but self-loathing.

in his directorial debut The Ceremony (1963)

Laurence Harvey played roles of disliked men; broken men; loathsome men. To them, he gave the brutal honesty of self-doubt and self-loathing, often coupled with the inability to articulate these feelings—or even to fully understand the feelings for themselves.

His most famously remembered role today is probably Raymond Shaw in The Manchurian Candidate, but it is both typical and atypical Harvey. Typical, in the sense that his character is pretty universally disliked by all the other characters for much of the film, and also his emotions are tightly controlled, cold, and hardened. But, atypically, Raymond Shaw can articulate what he feels and understands about himself. He just has to get a little drunk first to say, “I’m not lovable. Some people are lovable, and some people are not loveable. I am not lovable.”

In his characters, he captured the angsty longing of James Dean, but without the openness; without the bare emotions; without the yearning reach toward other humans. As a teen Dean devotee, my innate alignment with Harvey’s work makes perfect sense to me. It appeals to the unconfident child with plans to show themselves to the world within a carefully chosen and constructed presentation.

It is a tricky business transposing screen persona over a fully-formed human person—and I really try to steer away from that in the general sense (*everyone ever trapped in a text thread while I discuss my favorite performers is now laughing heartily at this statement*). I do not know enough about the short life of Laurence Harvey to exhaustibly essay on it, but all due consideration to the death of the author, I can tell you why his screen persona—which often slotted in with his projected public persona—compels despite its carefully structured coldness.

His Joe Lampton in Room At the Top is fully concerned with the work of self-presentation. How can he react to the trauma and pain of life in a way that gives him strict control and power over his image to others? Of course, in this film, his image control is primarily routed through destructive and deeply misogynistic interactions with women. The self-loathing is strong here, and so is the childhood trauma. (He even steals a beat from James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause writhing-in-turmoil-with-a-toy-in-the-street performance near the end of the film.) The story concerns itself with the catastrophic ills of classism, and wealth’s casual habit of ignoring, dismissing, and then crushing to dust any would-be rebels in the system. Truly, an evergreen subject.

I recently rewatched this for the first time since my own angsty teens, and I was struck pretty much the same: adoration for the resolute clarity Simone Signoret gives her Alice, and a resigned *yikes* floating in the general direction of Harvey’s messy, messy Joe.

Joe is truly so very unlikeable in his attempts to beat his oppressors by becoming them. Harvey’s performance here works as a sort of thesis for his entire career of characters: resolutely individualistic, powered by self-loathing, somewhat irredeemable, yet still lit with a spark of uncanny energy. In every film, he was never anything less than calmly chaotic.

(his characters can oscillate between chaotic neutral and chaotic evil—but rarely even begin to whisper at a hint of chaotic good)

This is true even if you watch his early cinema work in England when he was more than once cast as some sort of charming rapscallion, life-of-the-party (perhaps more in line with his public self: a jet-setting, stylish Elizabeth Taylor BFF who managed to clash with seemingly every single introverted/subdued/serious actor he ever worked opposite). It is wild to see him play characters like the scamming talent agent in 1959’s Expresso Bongo (a fever dream of a film co-starring my very lively personal fav Sylvia Syms): a character who is likely intended to be seen as a troublemaker, but a fun one—yet in Harvey’s hands comes across as a somewhat unhinged menace.

This character type is a menace! It’s the archetype selfish conman who is always making plans to make money and treats the woman who loves him like trash while he’s bouncing off to another probably illegal scheme. Cinema is rife with them. Often, they’re a lot of fun to watch. Other actors use their own reserves of personal charm to smooth the rough edges; to make these loathsome men appealing. Instead, Laurence Harvey barrels full-throttle into forcing a response like, “god, there is no way I could spend more than two minutes with this person without screaming aimlessly in rage and frustration.”

In Darling, he’s enigmatic and absolutely without empathy. Both he and Dirk Bogarde play the male foils to Julie Christie’s incorrigible Diana Scott, but Harvey’s openly shallow work contrasts with Dirk Bogarde’s deeply shaded performance. Harvey offers no depth of emotion or feeling. It is obvious that his character is merely a shadowy projection. He makes no effort to humanize. He has built a blank façade. Harvey plays him as a compelling snake with no plans to warm up. Christie and Bogarde play people who cause varying degrees of harm through selfish pursuits, but the hook is that they do want to be happy, to be fulfilled, to be loved. Harvey’s Miles Brand shows no such desire—only a twisted, lightly-smiling desire to have control and power.

What is self-presentation if not an external action of innermost power and control? To dissect our own self-presentations is to ask questions: How do we see ourselves? How do we want to be seen? Every performer deals extensively in self-presentation. It is quite literally in the job description (I have now written “self-presentation” so many times it has lost all meaning and I am unsure how to pronounce it out loud anymore). But, few performers have ever made as much a concerted effort in pointing out the façade as Laurence Harvey did in his work. Is it damning him with undeserved praise to say that your loathing is what he expected? Yeah, his performances of being human register as somewhat cold, bleak, and out-of-step with any semblance of communal feeling. god knows, the cruel and cold male anti-hero concept is so dull and predictable (and always has been). I am not here to gas up that.

I am interested in the idea of that façade—the tightly controlled self-presentation—as a concealing act of self-protection.

“I’m a flamboyant character, an extrovert who doesn’t want to reveal his feelings.”

What happens when a flamboyant character (just look at his signature hairstyle—out there looking like a dandy from an earlier century), an extrovert who doesn’t want to reveal his true feelings, directs his first film?

You get The Ceremony (1963), a deeply idiosyncratic, stylized film that reveals many, many feelings. It is structured madness; structured chaos. The staging and shots are both uncluttered and extreme: purposefully drawing attention to themselves. Emotions are kept close inside with delicate facial expressions—and then exploded with full-body, uncontrolled movement.

I may be outing myself as a pretentious weirdo, but this is truly a favorite moment in cinema for me. There is a discomfort that comes from watching people let their bodies feel in outrageous waves.

This is a scene between Harvey, who has just escaped prison, his girlfriend Sarah Miles and younger brother Robert Walker Jr.

There is a line near the end of this clip that hits at one of Harvey’s themes in the film. He is specifically referring to the brutality of prison on a person’s spirit (side-note: abolition now!), when he talks of being reduced to the shadow a man.

“In there, I had time to think. I had never really taken the time to think before. What was I trying to prove? Where did it go wrong? And then I realized that it was too late. I was going to die knowing that I hadn’t lived. Do you understand what I’m trying to tell you? They try and reduce you into a shadow of a man. Your body begins to feel as if it doesn’t belong to you. Eating and eliminating. Detached. Your arms and legs begin to feel as if, as if they’ve been sewn on. Don’t think. Don’t feel. Flesh. Nothing. And you begin to believe it.”

While specifically a reference to the prison experience, it is also representative of some of the overarching themes (it can get a bit opaque and metaphorical in this film: just the way I like my pretentious cinema yum yum delicious) of power and control: who has control? how is power used? what makes a person human? how is each person’s humanity to be protected or destroyed?

To feel, as a person, like nothing more than a shadow—nothing more than flesh—is a grievous pain. Loss of autonomy is a grievous pain.

How do we see ourselves? How do we want to be seen? … How do we protect ourselves? How do we construct an image that cannot be breached? If we project coldness and inhumanity, do we save ourselves like the weakest prey puffing up before a predator? If we are sure we’re unlovable, can we say that being loveable is not the point?

Laurence Harvey’s canon of performances is filled with characters certain of their unlovability, and just as quick to present as unlovable in turn. Quick to project a self-image that prizes control and individual autonomy over relationship and community.

I think feeling loveable or not loveable is a universal human concern. It certainly looms quite dominantly when we’re young figuring out how to be. It has always explained to me why Laurence Harvey’s work compelled me. It said, "Build up your barriers! You’ll never be broken! (also you’ll never be happy!)”

Fortunately, I was also compelled in my formative years by two other male figures on my TV (look, I was homeschooled in the woods—I didn’t really see other adults except from my media): John Cassavetes and Mr. Rogers (honest to god, someday look for my comparison post about these two that’s been sitting as a draft since December).

Cassavetes: “And I don’t think a person can live without philosophy. That is, where can you love? What’s the important place where you can put that thing—’cause you can’t put it everywhere, you’d walk around, you gotta be a minister or a priest saying, ‘Yes, my son,’ or ‘Yes, my daughter, bless you.’ But people don’t live that way. They live with anger and hostility and problems and lack of money—with tremendous disappointments in their life. So what they need is a philosophy, what I think everybody needs, in a way, is to say, Where and how can I love, can I be in love so that I can live—so that I can live with some degree of peace? You know?

And I guess every picture we’ve ever done has been, in a way, to try and find some kind of philosophy for the characters in the film. And so that’s why I have a need for the characters to really analyze love, discuss it, kill it, destroy it, hurt each other, do all that stuff—in that war, in that word-polemic and picture-polemic of what life is.

And the rest of the stuff doesn’t really interest me. It may interest other people, but I have a one-track mind. That’s all I’m interested in, is love. And the lack of it. When it stops. And the pain that’s caused by loss or things taken away from us that we really need.”

Mr. Rogers: "Love is at the root of everything, all learning, all relationships, love or the lack of it."

I did not start writing this post intending to end up with Mr. Rogers at the finish, but I cannot say I am too surprised either. I did start writing this wanting to articulate why Laurence Harvey’s work meant something to me at my most impressionable ages. Truly what does a performer dead more than twenty years before I was born have to say through their film roles to a youth in the mid- to late-2000s if not, “Here is one way to live. You’re not gonna like it. But you’re gonna understand it anyway. Deeply understand it.” An extrovert who doesn't want to reveal their feelings? COULDN’T RELATE. I’M UNKNOWABLE! I’M UNKNOWABLE! (I scream into the void while absolutely oversharing, hence this very post on my own blog).

It is hard being human. It is hard to be human with other humans. It is hard to know yourself. It is hard to express yourself. What Laurence Harvey did with his work was to show the excruciating effort it takes to master an “unbreakable” self-presentation, and the open wound of making yourself invulnerable. The call of the void whispers that invulnerability is power, but the truth is in relationship and community with each other. <3

Please clap for the tremendous amount of self-restraint it took to not embed this clip of Daniel Tiger singing about being a mistake at the end of my post and thereby completing the parody of myself that is all this. Disgusting!

Also, this post is dedicated to Emmy—whose recent discovery of Laurence Harvey set me off on this journey down the old memory lane.

And, also to Kate—whose dedicated refusal to appreciate Laurence Harvey inspired many teenage Blogger/Twitter/Tumblr feuds on Friday nights.