The Year of Joan Hackett

I love Joan Hackett. She was a singular actor. I embarked on the Year of Joan Hackett in a bid to complete her filmography.

I love Joan Hackett. She was a singular actor. Onscreen, she had the best and the biggest energy. She was sweet and savory. She was inimitable. She had an instantly recognizable voice and the hair of a turn of the century Gibson Girl. She could make you cackle with laughter or break your heart into tiny splinters. She was explosive and tender. She was overwhelming and gentle. Like the best of our immortalized actors, watching her onscreen is like spending time with a dear old friend.

In January, I was watching her in The Last of Sheila (1973) for the first time (I know! I know! A film made entirely for me that I somehow had not seen age fifteen late on a Friday night with a library DVD). I was thinking about how much I adore her work, and how much I actually hadn’t seen of her short career.

I embarked on the Year of Joan Hackett in a bid to complete her filmography. This is something I successfully did in 2023 with Sandra Dee (and never got around to writing about, naturally), and attempted and failed in 2024 with Audrey Hepburn (so close; I will circle back around to the Lady Hepburn). I am using Letterboxd’s version of her filmography (via TMDb) as it limits her work to feature films and television movies: 31 titles versus the 69 credits on IMDb (this still leaves me so many delicious 1960s and 1970s TV episodes to enjoy at my leisure).

The dark winter months were very successful and I watched many new-to-me Hacketts. I have admittedly fallen off since the summer, but, as the days grow shorter, my appetite for spending time inside laying about on my couch increases.

I have decided to chronicle My Year of Joan Hackett here, and update until I am completed. I have been keeping a ranking of Joan Hackett, and I must say that is purely based on some indescribable Hackettness that I am personally determining and nothing else. Does the film give me the hit of Hackett that I crave? Does Joan get to say or do something wild or chaotic or emotively tender? Is she brittle or is she full of life? The Hackett variations are myriad.

Joan Hackett Filmography

Joan Hackett Ranked

Support Your Local Sheriff! (1969)

Joan Hackett as Prudy Perkins was foundational for me, and I still love to rewatch. I never grow tired of her weirdo performance. All awkward limbs and deep, abiding rage. When she yells, “Death to all tyrants!” and tries to chain herself to a support beam at the city council meeting and they all respond like she has done this many times—perfection! Her chemistry with James Garner is so unbearably generous and fun.

2. Five Desperate Women (1971)

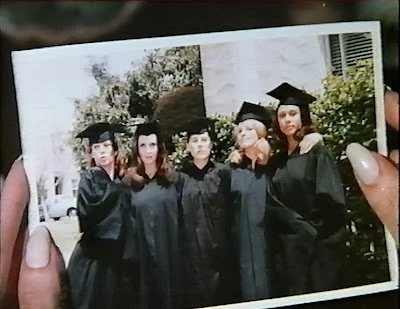

I first watched this eight years ago, and I was obsessed. Truly the stuff the TV movie dreams are made of. A perfect cast from top to bottom, but Joan Hackett still stands out as she spends her entire run-time lying profusely to everyone around her while wearing all manner of elegant fashion before breaking down and admitting she has a TV in every room playing constantly so she won't be reminded she's ALONEEEEE. There is nothing better than Joan Hackett amidst a group of women. You can watch on YouTube here.

3. The Last of Sheila (1973)

As mentioned above, this was a 2025 new-to-me film, and it quickly jumped into the top echelon of Hackettness. She is so good and vulnerable and brittle but with a very sharp edge. She plays everything just right. SPOILER IN WHITE TEXT (HIGHLIGHT TO VIEW): Based on her performance, I genuinely thought that she was one who belonged to the “You are a Homosexual” card, and that she was having an affair with Raquel Welch. THE SIGNS WERE ALL THERE (IN MY HEAD LOL). END SPOILER.

4. The Young Country (1970)

Okay, so this isn’t very good (and was remarkably hard to find to watch), but I do love visiting the wacky mind of Roy Huggins. The unfortunate thing is that he was always trying to make Roger Davis happen as one of his charming rapscallions, and well the man was full of menace onscreen! (He played the only man that Kid Curry ever killed!) He is somehow the lead here instead of Pete Duel who plays a supporting role (this all got sorted out when Alias Smith and Jones premiered the next year). None of this touches Joan Hackett though with her signature hair poof and the driest, smirkiest delivery. Perfection. I have probably ranked it too high, but it’s just such potent synthesized Hackettness. Joan Hackett + Pete Duel is also the smoothest delight. They have wonderful chemistry and their scenes together are the best in the movie. (I have also cheated here and added a photo to the slideshow from her guest appearance on Alias Smith and Jones, because she is just a perfect third with boys).

5. Reflections of Murder (1974)

The girlfriends are plotting murder on an unnamed island off of Seattle, and we are having a great time! Joan Hackett was the queen of full-bodied vulnerability, and she ably portrays a journey into hysteria. I loved her chemistry with Tuesday Weld. And, here, she also demonstrates her skill with acting alongside children. She always has a true sweetness and gentleness in that regard. Watch on YouTube here.

6. Rebecca (1962)

A truly short (sub-hour) live television adaptation of Rebecca (notably adapting the 1940 film, and not the novel), but oh my, she is so good as the Second Mrs. de Winter. I would have loved her in a full adaptation. She has that exact right combination of nervousness and steeliness and freshness. This one is somewhat of a rarity and I had to rent on VHS from my local video store.

7. The Other Man (1970)

Isolated house on the rainy northern Pacific Coast! Melodrama! Joan Hackett doing her greatest hits! This is a really strong Hackett performance. The edgy vulnerability. The gentleness that can explode when provoked by cruelty. The fight between staying safe (internalizing emotions) and being authentic (emotions out loud). She is the star here, and works well with Roy Thinnes.

8. The Group (1966)

A wonderful cast of women makes up the group, and there is not an underwhelming performance in the bunch. However, obviously, I am Hackett-biased, and I think she brings a very lovely and very Hackett brittleness here. She stands out even among all the great actors around her. She also just looks so good in a 1930s haircut and dress.

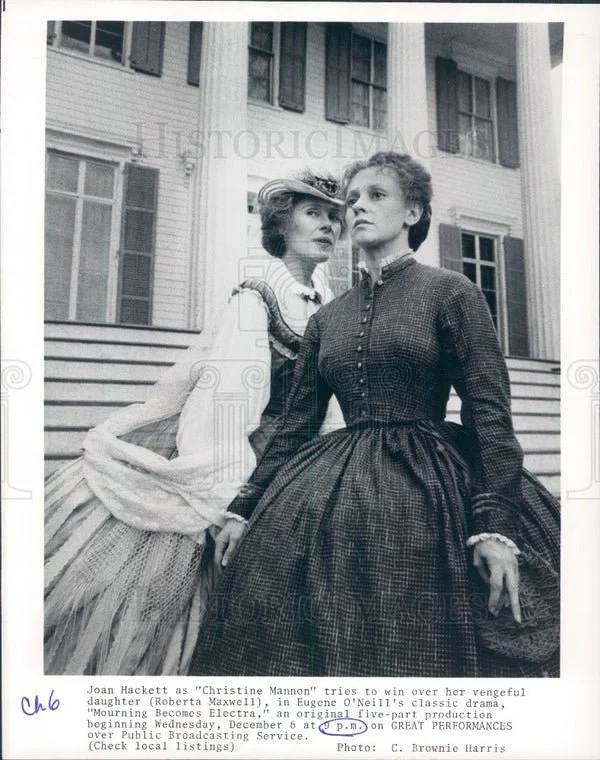

9. Mourning Becomes Electra (1978)

Rotten children!

I suppose one must blame the rotten parents!

But, oh the delicacy that Joan Hackett unspools in her portrayal of Mother Mannon! She gave such depth of pain and quiet suffering. You could feel when Christine felt out-of-control. I was rooting for her.

One murder would have actually been great for the Mannons. A good foundation for everyone to grow from.

But rotten children!

10. Assignment to Kill (1968)

Joan Hackett so cute and charming in this! I love her flippy hair and slacks and ties. I love her eye rolling and quipping. Alas, however, she is not the lead of the film, so we do not get to spend every minute of screentime with her present. It would have been a better film if that was the case. When her character departs the film, so does all my interest. This is a really fun role to see her in, and I will pretend she left that boring man and safely continued her quipping in slacks and ties for the rest of her days.

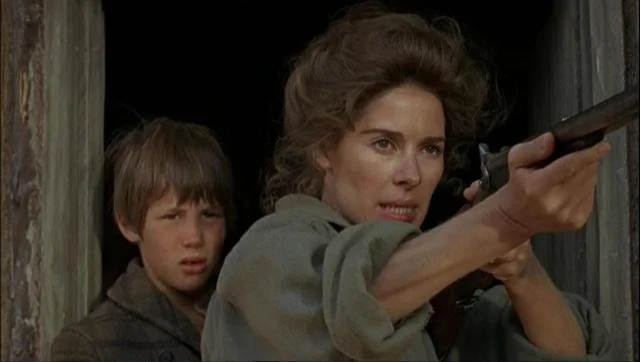

11. Will Penny (1967)

The final Hackett in my year of Joan Hackett, viewed on December 31st. It was an apt final film as it contains so many elements of Hackett Greatness. She is warm, tender, outspoken. She has great hair. She brings out the best in the child performer playing her son. She is so very loveable.

Here, she is even manages to humanize Charlton Heston, which was shocking to me personally. She also shifts with ease to blend with the chaos when Donald Pleasence and sons (Bruce Dern!!!) descend upon the film.

12. Only When I Laugh (1981)

I am simple and I love watching charismatic actresses spout Neil Simon dialogue. Joan Hackett's only Oscar nomination. She should have won. She really is playing a perfectly distilled version of a Joan Hackett character. She’s strong and falling apart at the same time, and so wonderfully loveable.

13. How Awful About Alan (1970)

It would have been entirely easy for this film to have cast Julie Harris and Anthony Perkins as sensitive, awkward freak siblings and called it a day (I would have still watched that film) without bothering to cast anybody good in the role of the patient and supportive fiancé. Thankfully, they cast Joan Hackett. She's darling here, and does some of her inimitable work managing to imbue goodness with such shape and substance. (A true Pisces, I suppose.)

14. The Possessed (1977)

Don’t ask me any questions, but yes, I would love to go to Joan Hackett's School for Girls! This is the absolute pinnacle of Joan Hackett stressed-out acting—she reaches spontaneous combustion levels of work-based anxiety (whom among us cannot relate). This is a performance that really shows how she can hit every big and small beat so perfectly.

15. The Terminal Man (1974)

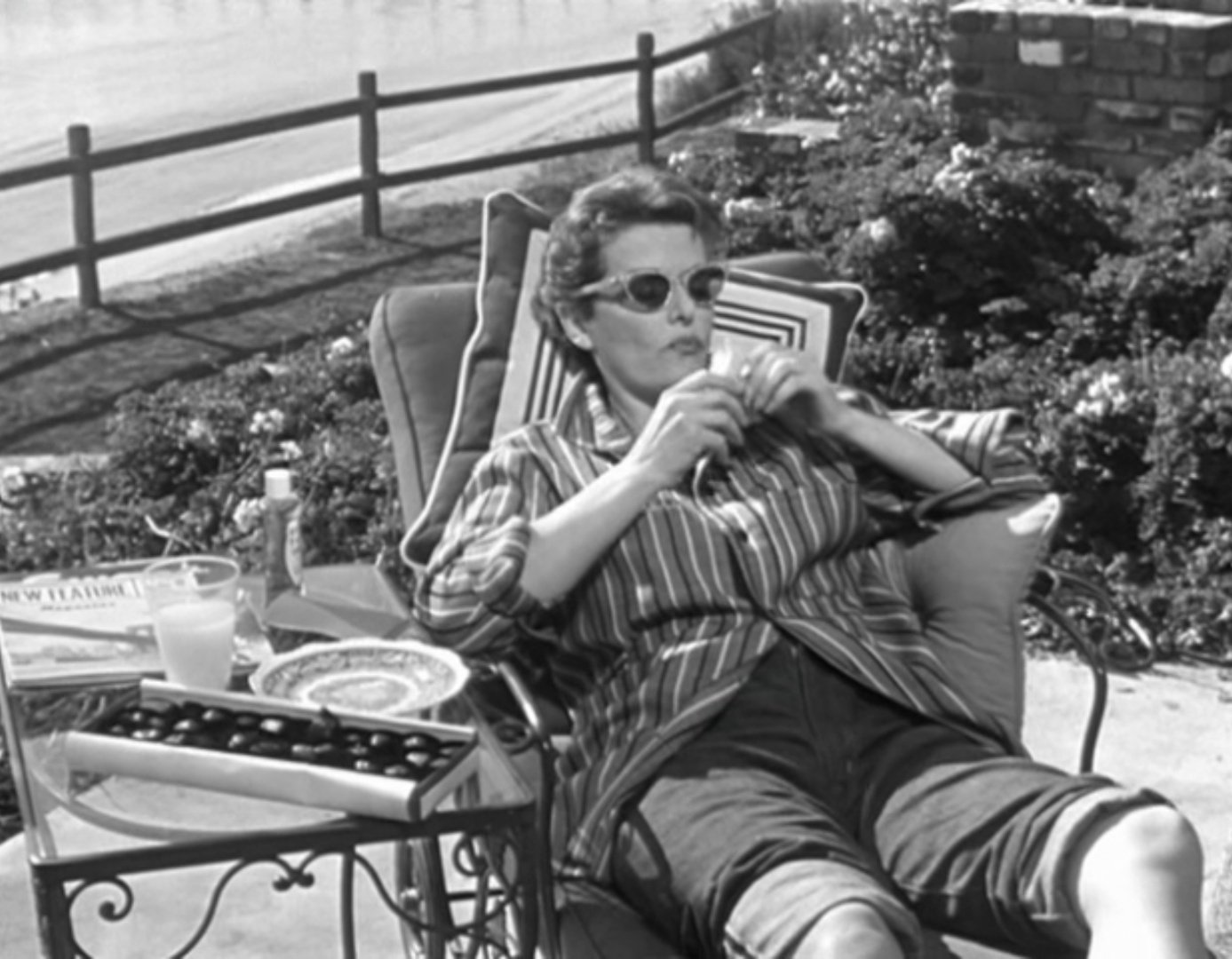

Joan Hackett such a competent presence, and although there were some attempts at weighty philosophizing in this film, I was--shallowly--mostly obsessed with her pristine monochrome outfits and perfectly styled short hair. (Slicked back shower look was truly a dream.)

16. The Treasure of Matecumbe (1976)

A deeply questionable film that cannot be recommended. Joan Hackett does however have poofy hair, a wild accent, a job running scams, and a gentle aunt energy with the child leads.

17. Dead of Night (1977)

TERRIFYING. I am not equipped for this kind of imagery. Oh, she is so good here as a mother who is losing her mind with grief and maybe also whoops summoning demons? Many actors talk about how it can be hard to act opposite children, but Joan Hackett worked with children many times and always has such a perfect energy match to them.

18. Pleasure Cove (1979)

A nothing of a TV movie, but she is so delightful as one-half of a pair of battling exes who show up at the same resort. She is a professor leading along a young dummy of a boyfriend, and generally being her caustic best. She is simply too much fun and I love her big hair and track suit.

19. The Escape Artist (1982)

I find it singularly painful to watch films starring the O'Neal children. Vulnerable children with no advocate; no safe adult. This one has a distinct sadness as Griffin O'Neal's character spends the film trying to cope with the enigma of his father's death and the confusion and grief of that loss. However, Joan Hackett knows how to work with children, and she is really lovely here in one of the final roles. Her interactions with Griffin sing with such a gentleness and genuine sweetness.

20. The Long Summer of George Adams (1982)

A Joan Hackett + James Garner reunion! Their chemistry so exactly right thirteen years after Support Your Local Sheriff! This was one of Hackett's final performances, and her energy is the heartbeat to this story. (I do not forgive Garner’s character for his betrayal though!)

21. Paper Dolls (1982)

A Joan Hackett v. Joan Collins Joan-Off! A small supporting performance from Hackett, but she is fun as a demanding stage-mom of her teen model daughter. She is all business with a slicked back pony.

22. The Long Days of Summer (1980)

Joan Hackett is strictly playing Mom. But she really is so good, and I have come to realize over this year of Hackett that she works exceptionally well with children!

23. One Trick Pony (1980)

Joan Hackett is a minor character in this film, so she does not have much to do. She does get to appear wise and wry and also looks great as a sleek blonde. She is the smartest one in the movie and I would have loved to watch her movie.

24. The American Woman: Portraits of Courage (1976)

When I say Joan Hackett completism, I mean COMPLETISM. This is a fascinating artifact of 1976. She plays Belva Lockwood, lawyer/politician, for one scene recounting a story about defending a woman in court against her husband. Not a lot to say here, but I do think that Joan Hackett always looks incredible with poofy late 1800s hair and she does have such gravitas. A natural pick for the role.

25. Class of ‘63 (1973)

A TV movie with so many unfulfilled plot-lines, I wondered if the version I saw was edited? Anyway, my only feeling after watching it was: Joan Hackett, a queen! Leave both that short loser and that tall loser behind. Live your life!

26. Mackintosh and T.J. (1975)

This film is bleak as hell. Joan Hackett typically wonderful in a limited role. She plays vulnerability with such warmth and clarity.

27. Stonestreet: Who Killed the Centerfold Model? (1977)

One thing that simply was not utilized enough in Joan Hackett’s career was casting her as a villain. She really is fun here as a sinister lady with giant glasses doing evil business things from behind a phone. Watch on YouTube here.

28. Flicks (1983)

I believe this was her final released performance. Her parody vignette as a spaceship commander ala Star Trek is somewhat painfully unfunny, but not her. She is just a delight. Imagine the dream of her playing this role in a serious production.

29. Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video (1979)

Watched for Joan Hackett and she has a 5 second voice-only cameo 30 min in. *sigh*

I tapped out after that.

Unranked: Rivals (1972)

Started, but did not finish when I realized it was not a film I wanted to see. My friend Hannah Lynch explains the film in detail here. Films can be made about exploitation of children without exploiting child actors, but that does not appear to be the case with this film.

Joan Hackett in Progress

Lights Out (1972)*

*Turns out this is a lost film. Every mention I can find online from people who have seen it watched its original airing and have never forgotten how scared it made them. Seems like the only way to see it is in-person at Paley Media, so just let me add that to my list.

Playlist of Films Available on YouTube:

-Meg

MasterClass: Tyrone Power Teaches Chemistry

Today, we are learning from Tyrone Power and the totally unmanageable, all-encompassing chemistry he shared with every person he ever performed opposite. The man was an unbroken eye contact menace, a genuine magnetic force, and honestly, we are just lucky he never dabbled in cult leadership (in real life).

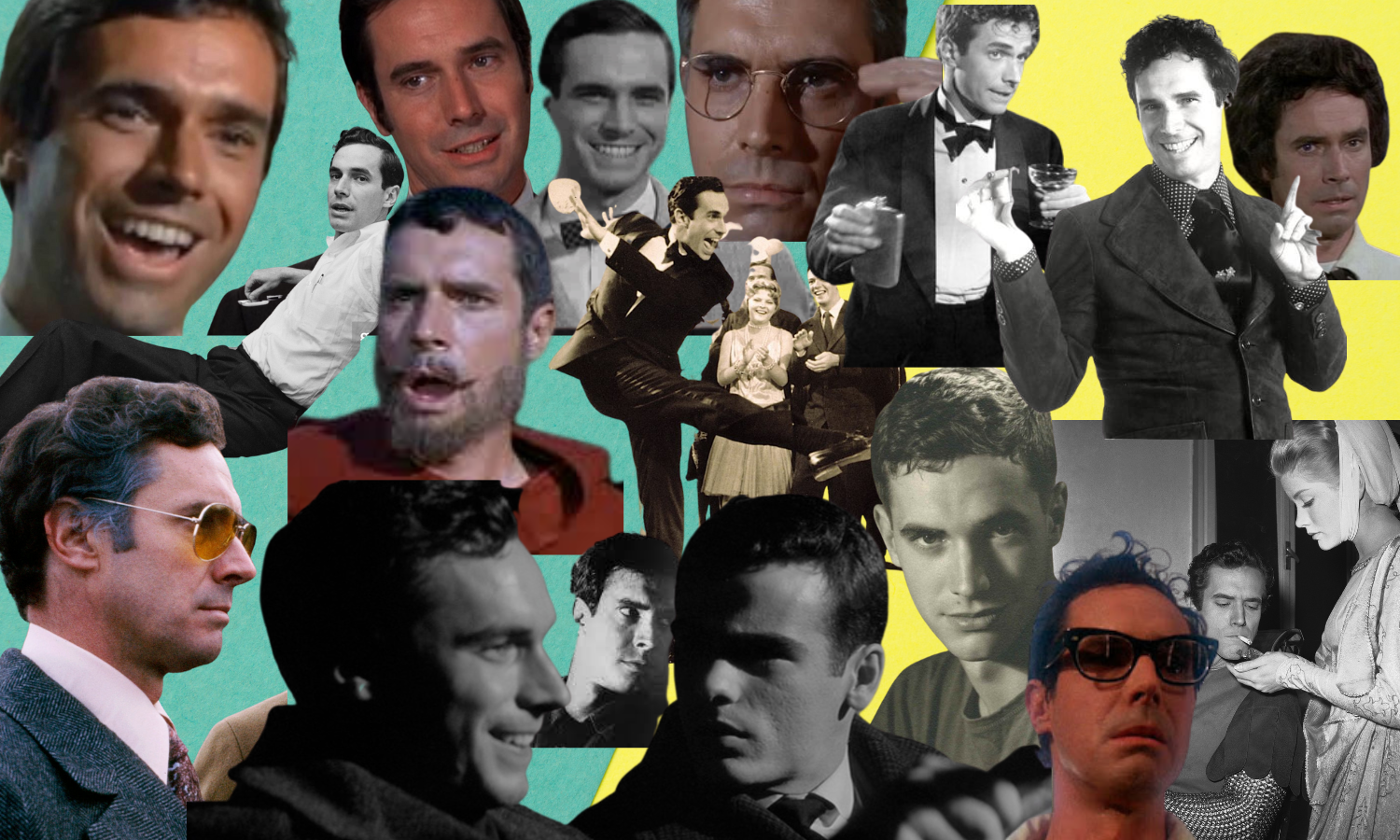

Hello students and colleagues, time to gather your notebooks, pencils, laptops, or maybe just your tablets that you’re pretending to take notes on but actually doing endless jigsaw puzzles on a random app instead. Anyway, if your first question is whether this header image is the worst meme I have ever made--the answer is no. I have made much worse.

Today, we are learning from Tyrone Power and the totally unmanageable, all-encompassing chemistry he shared with every person he ever performed opposite. The man was an unbroken eye contact menace, a genuine magnetic force, and honestly, we are just lucky he never dabbled in cult leadership (in real life).

Tyrone Power (or Ty-Ty as his friends called him, and by “his friends” I exclusively mean myself) is obviously a well-known classic Hollywood figure, and I suppose it could be disingenuous to call him underrated. However, as in his life, there remains a dismissive tendency to reduce him to a pretty face. That v. pretty face turned skill to happenstance and effort to chance. That pretty face combined with his obvious ease around women and his willingness to cry great big splashing tears on screen made him just a touch too adjacent to femininity for critical respect. How can this be trusted?

Alas for his critics, he was astonishingly popular and his films made bank, so his work had to be acknowledged and explained, and it was: pretty face; charming presence; likable boy. The blight of every beautiful actor to exist as an image--their levels left unexamined. BUT NOT ON MY WATCH! NO MORE, TY-BOY!

So, while I can (and will--with no notice and when you least expect it) opine with fervor on the Mariana Trench-depths of Tyrone Power’s work and efforts, today is for a narrower subject: chemistry. Chemistry is that effusive something that cannot be compelled. It usually satisfies most when the pair or group onscreen are equal nurturers to the dynamic--but, sometimes, one person just does more; creates more; is more. They do not need to grasp or struggle toward the effusive something, because they are the effusive something. That’s Tyrone Power. That’s behind the continuing durability of his presence and performing persona.

Ty had chemistry with everyone--EVERYONE. His ability to match his co-stars’ particular energies and idiosyncrasies becomes apparent in the fluid way his characters live on film. In The Mark of Zorro (1940, dir. Rouben Mamoulian), the way he interacts with Linda Darnell is very different from his interactions with Basil Rathbone, and yet again different from his interactions with Gale Sondergaard and others in the film. He shifts and modulates himself in an instant to fit with the person with whom he is sharing time and space.

With Linda Darnell (a repeat co-star), he is open and expressive, and there is a sweetness and playfulness present.

With Basil Rathbone, he comes to command and to posture--and theirs is the most flirtatious relationship in the film.

Ty -That’s a good effort, Capitán!

BR -The next will be better, my fancy clown.

Ty -The Capitán's blade is not so firm?

BR -Still firm enough to run you through!

Of course, there has been speculation about Tyrone Power's personal life and sexuality for many years, but as he did not leave behind a stated historical record, I am basing it on his own screen persona when I say that Ty Power is the ultimate old movie bi. He invented being a bicon. Let the record show! ("My fancy clown" is a great nickname to tell your crush that you care, okay.)

Power always focused so entirely on his co-stars, and because they have his full attention, they also have the audience’s full attention. The attentiveness usually manifests in eye contact. He loved long stretches of unbroken, sometimes unendurable eye contact. It acts as caress, a threat, a question, a promise--sometimes all of these at once, as seen in his scenes with Orson Welles in Prince of Foxes (1949, dir. Henry King). While Welles often liked to verbally and physically dominate in his acting, Power always dominated scenes in subtler ways. Opposite each other, they are shocking. Ty lets Orson physically control the scene, yet retains influence over the interaction anyway. He is too fluid and quick to be pushed over.

Neither was Power interested in pushing over anyone else either. I think about moments like this scene in Jesse James (1939, dir. Henry King). Ostensibly the scene is focused on Ty’s Jesse in conversation with Henry Hull’s loud, blustering Cobb. But, for emotional weight, the film actually needs the audience to focus on Nancy Kelly’s quiet, but vital Zee. Although Hull is stating important information to the plot, Ty physically moves his focus and eyes to Nancy Kelly. The audience’s attention follows too. What we lose by ignoring exposition, we gain in understanding the emotional motivations of the characters--Zee, in particular.

Tyrone Power’s acting choices were often subtle, but his characters mostly were not. In his pre-war films, he is buoyant and effervescent; all movement and flailing limbs and--in the 1930s especially--occasionally a high-pitched squeak. In Love is News (1937, dir. Tay Garnett) opposite Loretta Young, he floats. When he starred in the film’s post-war remake That Wonderful Urge (1948, dir. Robert B. Sinclair) opposite Gene Tierney, he is grounded. The post-war Ty Power is more contained. Gene Tierney is his perfect co-star. When it comes to silent staring contests, no one matched him like she did. Solemn eyes and deep feelings.

in The Razor's Edge (1946, dir. Edmund Goulding)

But, when they perform joy, it brings joy. And That Wonderful Urge is a glorious bit of let chaos reign we’re going to live and die on this chemistry filmmaking.

Tyrone Power had such a charismatic and fun presence, one is forgiven for not noting that he mostly played an alarming number of characters with charming, yet societally destructive tendencies. A whole spectrum of “hmmm, well this is troubling, but I guess we’re letting him get away with it. Good for him maybe?” If you have never seen The Black Swan (1942, dir. Henry King), I truly could not properly prepare you for the level of ethically horrifying moments present. Truly unjustifiable. He scampers around with perfect ease, however: flirting with absolutely everyone and letting George Sanders call him “the prettiest thing I’ve ever seen.” The dynamics of his relationship with Maureen O’Hara is a clear-cut nightmare, but they dubiously pull it off through sheer force of will (from her) and unbroken eye contact (from him).

Perhaps the pinnacle lesson in chemistry comes from two of Ty’s darker films: his final film, Witness for the Prosecution (1957, dir. Billy Wilder), and his favorite role, Nightmare Alley (1947, dir. Edmund Goulding). In these, he not only has precision chemistry with each one of his costars--modulating his performance to their energies in every moment--but he also plays his ultimate trick on the audience. Playing a slippery wronged man in Witness for the Prosecution and a scheming quasi-spiritual leader con artist in Nightmare Alley, he looks out of the screen and manipulates us! He knows exactly what to do to draw us in--look into his eyes closer, closer, closer--until we’re locked in, believing it all, following him anywhere. It’s Ty Power’s world, and we’re just lucky he never started a cult.

Additional notes:

Every time I wrote “Chemistry” in this post, please know that I out loud replied, “Yeah chemistry!” like I was in Guys and Dolls, and it took maximum restraint not to type it out like that.

Ty-Ty even had sustained eye contact with my cinematic nemesis Randolph Scott, and that is honestly hurtful to me.

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 07/08/2021.

-Meg

The Sinister Fun of Bradford Dillman

“By my reckoning, in over four decades I’ve been personally responsible for the demise of well over a thousand people. Heck, at Jonestown alone my Kool-Aid took out over nine hundred, and I’ve blown up the Queen Mary twice. Heroes are heroes. They pay the single greatest price of celebrity, the loss of privacy. This explains the army of bodyguards employed by some to keep the adoring multitudes at bay. Villains don’t have these problems. Me, I’ve never been bothered in a bar or boite. People can’t be sure I’m not carrying a knife or a gun.”

It is April, the sun is shining, and life is returning to some of our weary bones after what can only be described as a long, harsh winter of total discontent. In short, it’s Aries season, friends; and there is no better time to talk about charismatic villainous virtuoso Bradford Dillman (who would have turned 91 this April 14th). Bradford Dillman was an omnipresent actor in Hollywood for decades with a range that took him from The Actors Studio--debuting on stage with James Dean--and originating the role of Edmund Tyrone in the Broadway production of Long Day’s Journey Into Night to creature-feature horror and endless guest-starring roles attempting to kill the heroes in seemingly every 1960s and 1970s television program. He also kissed an ape in Escape From the Planet of the Apes.

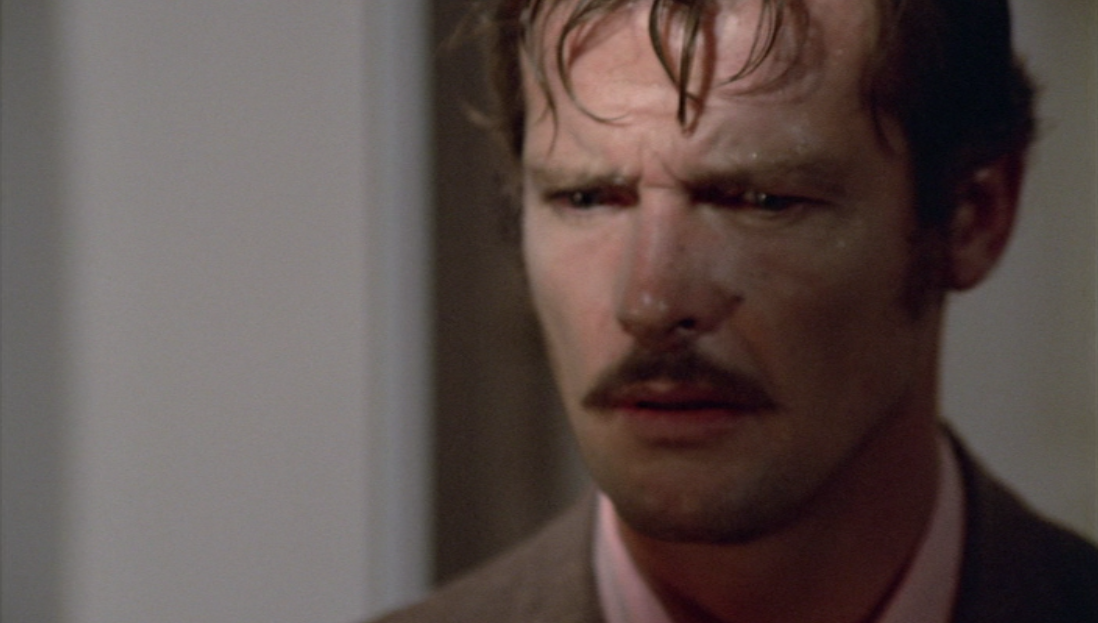

Bradford Dillman is an heir to Peter Lorre and predecessor to Michael Shannon in the spectrum of actors giving us high-caliber sinister charm all mixed up with genuine emotional connection. He had the best evil smile in the business: a bent, slightly twisted smile that promised chaos--or at the very least some premeditated malice. His presence filled up all the empty spaces in every medium he appeared. A particular maximalist specialty of Dillman’s was the extended close-up on his face as it moved through dichotomous emotions--joy to rage; sadness to glee. He was acutely aware of movement in his face and body, but at the same time seemed to understand that he was supposed to provide an experience that was not quite human, more like human+. Why go out quietly, when you can go out screaming, howling, and/or cackling?

One of his early film roles was in Compulsion (1959), dir. Richard Fleischer, a fictionalized retelling of the Leopold and Loeb murder and trial. He played Artie Strauss (Loeb), a petulant 18-year-old rich boy who has never experienced a single consequence in his life and is convinced of his own superior intellect. He is as terrifying as he is charming, and his dominance over his (boy)friend as played by Dean Stockwell is the kind of performance that does not let you look away from it. Certainly not when he can be found carrying on an entire sinister conversation with a teddy bear. He shared the award for Best Actor at Cannes with co-stars Stockwell and Orson Welles (but not the teddy bear, which was a total snub). Compulsion is a film which is at times ethically dubious (for one, the murdered child is given almost zero consideration), but is at all times a work of performer-first filmmaking that builds a tremendous amount of tension, lets its actors run wild, and also contains a classic Welles’ fake nose (and fake eyebags?).

Dillman began as a method actor in important productions™, but since he and his wife Suzy Parker (supermodel; inspiration for Audrey in Funny Face) had a large family together, after she retired, he pivoted to being what he called a “Safeway actor”--anything to put food on the table. This is where he really shines: leaving a legacy of untrustworthy characters with intoxicating charm in every possible kind of film or television production. He was the man to go to for southern gothic werewolves or cult leaders or egotistical supervillains, and also sad dads or sweet dates-of-the-week for Mary Richards, or if you needed someone to play the nephew getting murdered by Uncle Ray Milland in an episode of Columbo. (My kingdom, my kingdom for an episode of Columbo with Bradford Dillman playing the murderer! Come on, Robert Culp and Jack Cassidy--stop being so greedy!)

One such unassuming production that got injected with Dillman was Jigsaw (1968), dir. James Goldstone. Jigsaw is a drug-trip murder mystery of uncommon chaos. (One wonders if even the film stock itself was laced with LSD?) It is also total fun, and perhaps even the platonic ideal of a sinister fun Bradford Dillman performance. He plays a repressed, emotionless scientist who wakes up with amnesia, blood on his hands, and in a room with a dead body. Suffice to say, the plot does later require him to trip on acid for ten minutes so he can remember (that’s how it works). The film was shot as a TV movie, but the content was too hot, so it got a theatrical release instead. Bradford Dillman has a great time, and the film plays up his unmatched ability to depict mania. Aside from the unfortunate use of a gruesome murder of a woman as essentially a plot mcguffin, this film offers perfect 1968 colorful+chaotic vibes.

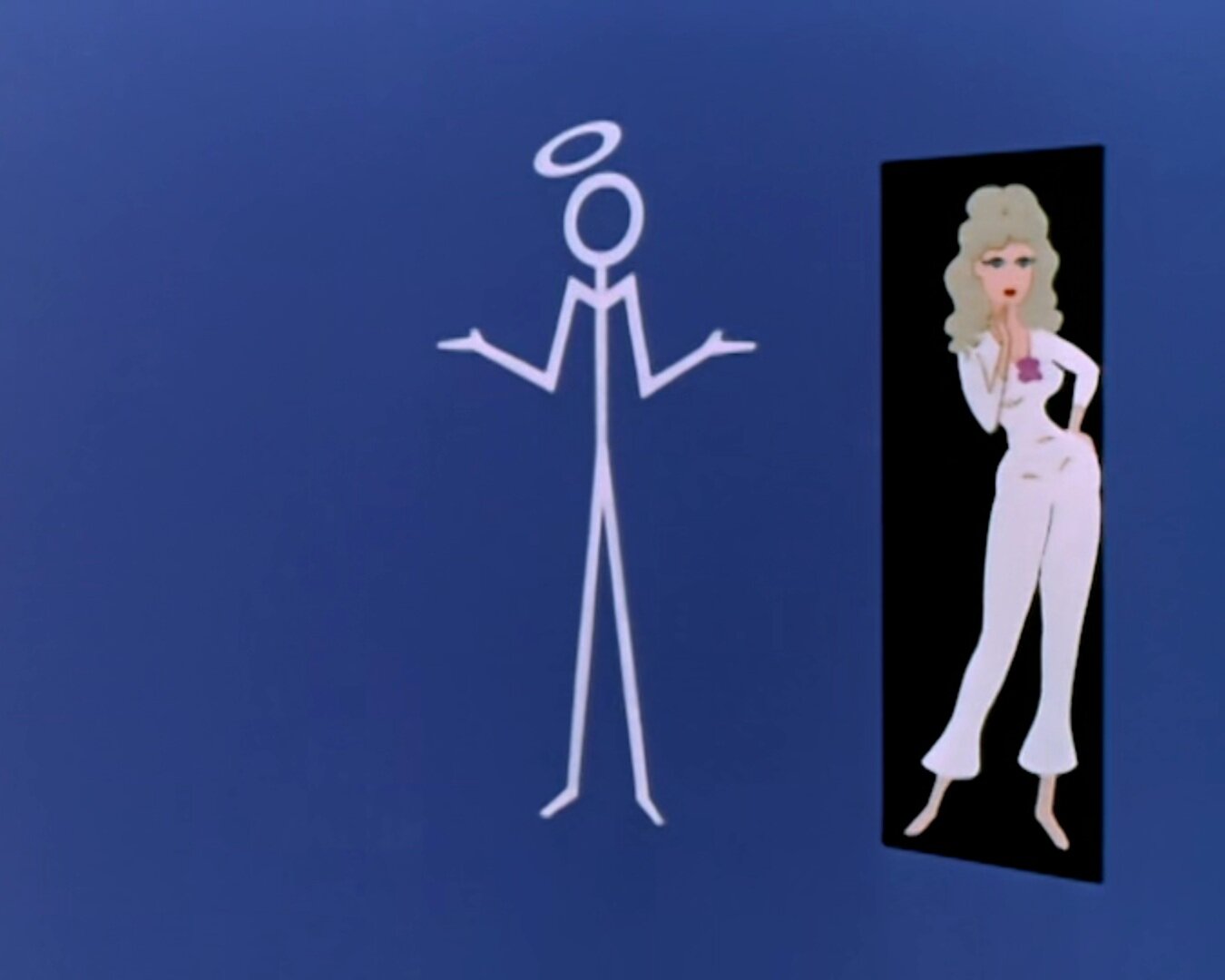

That same year saw a theatrical release of another American television production with The Helicopter Spies (1968), dir. Boris Sagal, a two-part episode of Man From U.N.C.L.E. edited together as a single film for an international theatrical release. It contains an astonishingly fun performance from Dillman as the leader of a cult called The Third Way. Everyone in the cult (aside from him) is forced to dye their hair white blonde to match The High Priestess, while he wears an entirely white outfit (suit, shirt, shoes). Cult members greet each other by saying, “Keep the faith!” while offering a thumbs up. Naturally, he has plans to take over the world, charms absolutely everyone into believing him (including our two heroes), and goes on scamming. Because it is Dillman, we are never quite sure whether he is maliciously scamming for power and using the cult as a means; or whether he is maliciously scamming for power while actually believing in the cult. Delicious!

It is that level of morally unstable character (to borrow a line from The Naked Spur) that makes even supporting performances in films like Five Desperate Women (1971), dir. Ted Post, so much fun. The titular women are Joan Hackett, Stefanie Powers, Anjanette Comer, Denise Nicholas, and Julie Sommars. They are college BFFS reuniting on a private island cabin after five years--and they are a "mess" (some of them don’t even have husbands or babies yikes!). The chemistry between the women is genuinely perfect, and is a great intersection of heartfelt and camp. What we know, but the women do not, is that a murderous man is currently loose in the area. Naturally, our suspicion falls on Bradford Dillman as the boat captain who ferries them over to the island. He is a real weirdo and alienates them all almost immediately by explaining nutrition and how they clearly do not understand health like he understands it. Bradford Dillman keeps us dancing the whole time on the power of his sinister reputation alone.

This reputation for crafting exceptionally twisted...but fun characters (imagine I am saying that in a Sullivan’s Travels-like “with a little sex in it” cadence) kept him employed for decades. One of his final films was the Roger Corman-produced Lords of the Deep (1989), dir. Mary Ann Fisher. Honestly, this film is weird and freaky--and worth it for the wild camera work and special effects alone. It opens with a title card letting us know the year is 2020, and “Man has used up and destroyed most of Earth’s resources.” *gulp* Bradford Dillman is the good company man who commands a huge corporation’s experimental underwater habitat. He is a sinister capitalist who will see everyone dead before losing a drop of profits. He slithers around saying things like, “Are you imPLYING that I would endanger the lives of MY crew?” and “We used to have a thing called an Ozone, Jack. Remember? ... You idiot.” It had been thirty years since Compulsion, and he had not lost an ounce of his ability to terrify and charm in equal measures.

These five films I have picked practically at random, and they do not even begin to touch on the levels of delight to be had in Bradford Dillman’s 40-year, 142-credit film and television career. (These five are all available on streaming, however. I would especially give a look toward searching these titles on YouTube, ahem.) You can choose any one of his 142 performances and find something to shock, awe, and/or entertain you.

And, he certainly did not always play the bad guy (not even in all of these five films), but just as his villainy was multifaceted--his goodness was complicated. Suspicious, dark, twisted and bent like his famous smile. The man knew how to show us a good time.

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 04/05/2021.

-Meg

An Ode to Sandra Dee

Let me paint a picture for you: It’s 2008, and I am 14-years-old, and newly attending a local homeschool co-op that meets every Monday in a church that’s forty minutes from my home. A homeschool co-op is an educational construct in which a bunch of homeschool moms (and it’s always moms) create their own insular school system and then teach the children of the other moms so that the art moms can just focus on art, the theology moms theology, the founding fathers moms the founding fathers, and the one mom who is really good at math tries to explain calculus to a bunch of teens who had taught themselves how to add and subtract and multiply and divide. There is no science mom.

This is as close to a classroom or school setting as I had ever been at the time, and I was delighted by the concept of school supplies at last (oh, how I had coveted those overflowing bins at Target), and naturally, immediately decorated my class folders with photos printed out at the public library. I had a James Dean folder, a Grace Kelly folder, an Audrey Hepburn folder, an Ingrid Bergman folder, and a Sandra Dee folder.

On that first Monday, the teacher-mom for the Sandra Dee folder class (it was something like American Citizenship 101) asked me who was on my folder. I said with enthusiasm, “It’s Sandra Dee!” This was a few months before I started my film blog, and I was eager for any outlet to talk. In a move that prepared me for every internet-splainer to come, teacher-mom responded, “No that isn’t Sandra Dee. Sandra Dee is a character in Grease. ‘Look at me, I’m Sandra Dee…’” (She did not finish the lyric, which clearly was a spectre from her heathen youth, as Grease was not co-op approved.) I was torn between knowing that adults should never be corrected, and also by knowing that, well, it was Sandra Dee on my folder. I went with a mumbled, “This is Sandra Dee, the actress.” Teacher-mom said, “No, you must be confused.”

And that was that. I saw no path to victory, but internal fuming, and going home and turning on my library’s DVD of Gidget (1959, dir. Paul Wendkos) that was on semi-permanent loan to me, and watching Sandra Dee prove all her doubters wrong.

Sandra Dee on-screen always proved her doubters wrong. And it was exactly what I needed. She remains one of my favorite people to return to on film: a friendly cinema companion. Her presence carries a quality, a tangibility, a gravitas that has never been allowed to be attached to her name by critics or public opinion. Lucky then that Sandra Dee did not need permission to be indelible.

She is unmistakable onscreen and entirely irreplaceable. The Gidget sequels are enough to tell you that. I mean, look, I am one of the bigger supporters of Gidget Goes Hawaiian, and yes, I did once tell Carl Reiner that Gidget Goes Hawaiian was a great film to which he responded, “No.” But, Deborah Walley as Gidget is just filling space. (And we do not talk about nor acknowledge Gidget Goes to Rome.)

Sandra Dee’s Gidget is alive, so fully alive. She is energy and enthusiasm and vulnerability and confusion and angst and elasticity. Her triumph in learning to surf feels like an earned triumph and the joy is palpable, and equally her scenes late in the film with Cliff Robertson’s predatory Big Kahuna are genuinely distressing because of her performance and her efforts. While Sandra Dee’s work is often tossed away as light-weight and sterile based on some historical collective false memory, her performance in Gidget should really be considered a direct predecessor to Elsie Fisher’s recent acclaimed work in Eighth Grade (2018). Sandra Dee gave us a realistic vulnerable yet determined teen girl who absolutely triumphs (with the loving support of her teen girl BFF) and teen girl me said, “You love to see it! Can you please ditch Moondoggie though? He is a drag.”

Sandra Dee’s known public image today and her original popularity was definitely predicated on her fulfilling some sort of white wholesome teen girl ideal for a 1950s American audience, but conversely her characters are boundary-crossing troublesome girls and young women. A defining characteristic across so many of her roles is a refusal to conform--in small ways and big.

In The Reluctant Debutante (1958, dir. Vincente Minnelli), only her second film, in the midst of swirling mania, she is the cool one--observing the hysteria with bemusement and maintaining her personal sense of self throughout. She assuredly partners with Kay Kendall and Angela Lansbury with a level of confidence that astounds. Her comic timing is already excellent here, and so is her ability to work ensemble. Her most perfect ensemble obviously being Come September (1961, dir. Robert Mulligan), a film that is surely one of the reasons cinema exists as a visual art medium. Sandra Dee and her tangibility are vital. With all due respect to the blonde youth actresses of the 1960s (I love many of them), how many of them would have the precise energy to match so comfortably on-scene with peak powers Gina Lollobrigida and Rock Hudson? There is a scene in which she psychoanalyzes Hudson that is masterfully funny. Her scenes with Bobby Darin are equal parts tentative and confident; sweet and confused. And with Gina Lollobrigida, she is sincere and kind with immediate rapport. There is no danger of fading into one-half of the obligatory forgettable youth B-couple of the movie--even in the presence of the dazzling Lollobrigida and Hudson.

The other two films in the Sandra Dee-Bobby Darin trilogy are also particular fun--with outlandish plots. In If A Man Answers (1962, dir. Henry Levin), she decides to change Darin’s behaviour with a dog training manual, and in That Funny Feeling (1965, dir. Richard Thorpe) via some classic mistaken identity she convinces him his apartment is actually her apartment. She is the firm center, sweetly spinning Darin and the rest of the film around in circles of befuddlement while she decides what she wants and when.

This aura of self-autonomy made Sandra Dee one of my figures of aspiration as a girl. In her characters, she lets the audience see the process of doubt and vulnerability while also making the decision. Her way of speaking is memorable: sometimes halting with clipped sentences and sometimes too many words spoken too quickly, but she really does always keep speaking.

Her openness onscreen is definitely why young me always preferred to rewatch her comedies rather than her melodramas--the vulnerability was too real. I have a very vivid memory of watching A Summer Place (1959, dir. Delmer Daves) as a 12-year-old hoping it would be another Gidget and my dawning horror as the melodrama played out. Sandra Dee played yearning angst and vulnerability so acutely--it hurt me. I must confess I have never rewatched the film, and to this day, hearing that wistful theme tune is enough to re-traumatize me.

Sandra Dee played Lana Turner’s daughter twice, most famously in peak melodrama Imitation of Life (1959, dir. Douglas Sirk), and again in the seedy Portrait in Black (1960, dir. Michael Gordon). Dee and Turner match up perfectly, both so adept at playing girls and women grasping for self-autonomy and self-preservation in a world that has no intention of making it easy. I wonder if Sandra Dee’s career had continued past her 20s if she would have found herself in Lana Turner-like roles?

Instead her final film appearance came in 1970, at the age of 28, in The Dunwich Horror (dir. Daniel Haller). She plays opposite another former teen-actor-with-substance Dean Stockwell in a freaky tale of the occult and monsters that feels subtly template-like for many films that followed. Her soft vulnerability amidst the chaotic production stuns. In Sandra Dee’s hands, Nancy is not a stupid, gullible woman led easily into danger, but an open and empathetic woman trying to balance danger against desire: a navigation that is true in every day life even when your job and studies do not include the possibility of your body becoming a gateway vessel for demons.

Oh Sandra Dee, I wanted to compose an ode to you, but I do not have all the words I need.

Oh Sandra Dee, you’re not a pastiche of people’s false memories, a relic from a plastic era, or the line from a song-- instead, resolve and humor, humanity and kindness, and an absolute knowledge of the ridiculousness of life--it all showed up on screen and bolstered a girl who desperately needed to see another girl triumph. 💖

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 09/05/2021.

-Meg

Deanna Durbin, my cinema ghost

December 4, 2021 was the 100th anniversary of Deanna Durbin’s birth. It is difficult for me to imagine the number 100 attached to Deanna Durbin. In my memory, she is always only just a little bit older than me, and always existing in the very same moment as I.

See, Deanna Durbin is my cinema ghost. Call it a parasocial phenomena, but she was a tangible presence in my childhood. A permanent fixture floating around the edges and spurring me to be just a little more indomitable.

The first film I ever truly remember the experience of watching was Three Smart Girls (1936). I was probably four or five. It was a library VHS and I distinctly remember where I was sitting on the floor watching it–absolutely transfixed by the sheer energy of Deanna Durbin. I was lost.

The closest library branch to my rural childhood home was about a thirty-minute drive away; and I cannot overstate how small this library is in square footage, yet on any given trip, you could find six or seven Deanna Durbin films on VHS. The spines all lined up next to each other with the titles and a signatory Deanna swirling making it clear. Other branches in the system had other titles and the librarians always helped me put them on hold.

I watched them all. I was a tiny little completist. I downloaded her presence into my life like it was a coding program from The Matrix. Her cinema persona was clever, resourceful, emotional, strong, a community-minded figure, usually working-class, a bit of an imp, and always holding the most secret ace in her back packet: her voice.

At some point, in every Deanna Durbin film, no one will listen to her pleas, all else will fail, she’s tried everything–and so she bursts into song. And, everyone is undone. And, everything falls into place.

That is glorious. That is an ephemeral sense of rightness that can be impossible in the world. So, we seek it out in the stories we make and the stories we drink up.

In my world, Deanna Durbin was the example and the ideal: build a loving community, wear fun clothes, talk as fast as you want, be chaotic and scheme a little bit, and when all else fails–start singing opera arias! My brothers can attest that the last one is not well-received without Deanna’s voice to match.

That never stopped me from playing a cassette of her greatest hits and loudly and defiantly singing along to the title song from Can’t Help Singing (1944). That film is a technicolor whirl that lives in my brain in its entirety.

Her entire filmography lives in my brain thus. Earlier this year, I watched Nice Girl? (1941) for the first time since I was a kid, and I was shocked to discover how much of it I remembered visually and even more how much I remembered who I was and what I was thinking and feeling when I used to watch it as a kid. How small and contained I felt, and how Deanna seemed to be on screen urging me to be open and large and unstoppable.

When I was ten, I got to stay up until midnight on New Year’s Eve for the first time ever. This event was shared with my childhood best friend, and we watched Lady on a Train (1945) for the first time and although she lives several states away from me now, we can still say to one another in passing, “It’s a pipe!” and know exactly what is meant.

When I was twelve, I finished my Deanna Durbin filmography at last by seeing Christmas Holiday (1944). I could not imagine anything more melancholy than her recording of “Spring Will Be a Little Late This Year.”

When I was fourteen, I mailed her a meandering letter of my adoration. I had written literally a dozen letters for years and never mailed them. I finally mailed this one–naturally without a self-addressed stamped envelope or anything for her to sign or anything. It felt too presumptuous. I just sent my letter off to France, and called it good. Not too many weeks later, I received this in return.

It felt entirely natural that my cinema guardian should know even fleetingly of my existence. I loved that it was a press still for His Butler’s Sister (1943), my favorite of her films. When she sings Puccini’s “Nessun dorma” as the finale and runs toward the camera as it dollys back–my heart stops every time. I remember playing it once while cleaning my apartment, and needing to stop the vacuum to weep. Human existence, amiright?

When I was nineteen, Deanna Durbin died, and I tried to write about her.

When I was twenty-four, I sat at a TCMFF screening of Three Smart Girls on 35mm, and when the film opened on her singing face, the audience erupted into applause, and I burst into tears.

I keep writing about crying over Deanna Durbin, which is horrible because she was genuinely one of the funniest performers working, and so utterly full of life. The grandiose energy is why she feels so vital. That energy is why she is constantly rediscovered and championed by audiences again and again. I am delighted every time I see someone like, “Deanna Durbin??? What the heck!”

I have tried for years to write about Deanna Durbin. I wrote posts on my teenage blog, on old movie message boards, Letterboxd films, rando tweets. I always think I can tackle my feelings and my perceptions of her and finally contain it into words that actually convey what I want to express. I thought I could do it today. Ahh hubris! I suppose I will need to return another time with more words.

I am twenty-seven now, the age she was when her final film was released. What does it mean that I am older now than my cinema ghost?

I will take comfort and joy and delight from her cinematic presence, and I will remember that stories and storytellers fill this human life with color. Our cinema ghosts stay with us.

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 01/02/2022.

-Meg

The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown (1957): we need to talk about Jane Russell in menswear

The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown has everything…

The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown // dir. Norman Taurog // United States

The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown has everything: Jane Russell in a cheap blonde wig, Ralph Meeker kidnapping someone, Keenan Wynn third-wheeling, Hollywood insider shenanigans, action intrigue, cops getting knocked out with ash trays, Una Merkel wise-cracking, eggnog-induced drunken antics, Adolphe Menjou gliding around like it’s 1937, and of course, confusing and troubling moral ethics baked right into the script!

Yes, this film is about a movie star falling in love with her violent and frightening kidnapper. And, also yes, Jane Russell is a pure powerhouse of charisma and Ralph Meeker is a rare and perfect male energy match for her.

Look, I love The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown. I need to enumerate every reason.

Let me give you the short pitch: It’s Noirvember (shout-out to founder Marya E. Gates), so why not watch Jane Russell swagger in a Double Indemnity-style wig while tussling with Ralph Meeker who is being violent, anti-social, and cynical---BUT IT IS A ROMANTIC COMEDY!

The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown defies explanation.

On one hand, it feels low-budget and takes place mostly in one location that could double for a set from a television show. On the other hand, it is Jane Russell, Ralph Meeker, and Keenan Wynn each at peak powers doing a cleverly-paced three-hander.

Jane Russell produced this film (her fourth film with her production company Russ-Field), and plays the lead: Laurel Stevens, a glamorous movie star frustrated by her limiting sex symbol status. Russell counted this as her favorite film (alongside Gentlemen Prefer Blondes), and it feels very attuned to her. Laurel Stevens knows the misogynistic game in Hollywood, and she is happy to name it, making it clear in diatribe against studio executives she shares with her assistant (Una Merkel !!!) right at the top of the film:

“Oh, sure, when they were pushing me around, it was just good business. But let me start dishing out a little action, and I’m tough and temperamental.”

She continues, speaking of desire for personal autonomy, “I’m just a simple business girl. I sell a funny, phoney commodity called sex, and if the customers are hungry enough to buy it, I run my factory in my own way.”

She heads out the door of her home to a waiting car taking her to the premiere of her new film, The Kidnapped Bride. Instead of chauffeurs, it’s Ralph Meeker and Keenan Wynn--and they literally kidnap her to hold her for ransom.

Laurel Stevens is in no way frightened of her kidnappers, and is instead horrified that the press and movie-going public are going to think this is a publicity stunt and turn against her. Her agent and film producer (Adolphe Menjou !!!) are worried about this too, so they are unwilling to report her missing. The kidnappers have her holed up in a Malibu beach house (Kiss Me Deadly crossover potential), but she is not going to make it easy.

Shenanigans ensue.

Jane Russell’s work here is supremely confident. She truly feels like she’s two feet taller than everyone else. She doesn’t glide through the film. She smashes her way through the film. She is funny, cynical, powerful, and so very present.

The wig comes off (spoiler alert!), Ralph Meeker’s Mike (not Mike Hammer, but god can you imagine!) becomes fixated with what that wig means in terms of authenticity. He apparently has some childhood trauma related to a candy store that lied to him about bubble gum and anyway that is why he hates phonies and is angry about a wig? Listen, I love it.

Laurel: "Look, what have you got against me, anyway?"

Mike: “I don't like phonies. When I was a kid, there was a little weasel that ran a candy store on Coney Island. Sundays and holidays, he put a big sign in the window: "Free Bubblegum." Only the store was always closed. I never got enough of hating that guy.”

This film was not financially successful, and the critics had mixed-feelings. In particular, critics felt very meh about Meeker’s rough and gruff performance, and wanted someone a little more classically funny. But, genuinely, his decision to play this ostensibly light comedy character as a smirking, brutalist cynic barely containing his ever-present rage is genius.

If he was less terrifying, I might feel a little better about the fictional characters’ happily-ever-after actually working out (LAUREL, RUN!), but as it is, Russell and Meeker play off each other in a perfect sync. In their mouths, rote 1950s studio dialogue is given life that it probably doesn’t deserve, and I am left quietly cackling to myself.

And, oh Keenan Wynn. What a genuine great. I have extolled his virtues here before, but really I always need people to really grasp how good he was as an actor. His Dandy here is the understanding sweetie of the kidnapping duo and the third wheel of a dangerously toxic long weekend in Malibu. He comes off as being just a little in love with both Laurel and Mike, and both of them continuously and selfishly use him to their own ends. For an intended comedic side-kick in studio comedy, he gives a surprisingly tender and emotionally-aware performance. Dandy is the unexpected little beating heart to the movie (and also my personal cinema avatar, but let’s not get into that right now).

I LOVE THIS WEIRD MOVIE.

Genuinely, I guess I can see why it was not popular in its contemporary release, because it is ever-so-slightly unhinged, but also please follow me on this journey to bring about The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown renaissance, so I can finally get a home video release.

I mean, Jane Russell, because of plot machinations, essentially only is seen in repurposed menswear throughout the film, and the power that has is indescribable.

Ralph Meeker only wears soft, comfy sweaters (SWEATER WEATHER) while ragefully smoking a pipe, and there is a quiet power to that as well.

It makes absolutely no sense that this film is in black and white instead of glorious technicolor (literally do not name your film after a color and then not have color), but also it oddly makes the most sense because, again, this movie is not a light studio comedy. It’s a film about Hollywood and all its darkness.

It is also a film in which Jane Russell gets drunk on eggnog and also in which she stone-cold sober knocks out a cop and steals his car!

I am literally lightly cackling to myself--out loud--alone in my apartment right now remembering how much this film delights me. I think those of us who love cinema have a myriad of reasons why we do. I know I certainly love cinema for the transcendent moments of beauty, for its ability to immerse us into another life, for the social connections, for the community it creates, for the visually stunning images. I also love cinema for sometimes being absolutely ridiculous. Film is a collaborative medium in its very nature, and sometimes, you take a step back in your mind, and survey a work like this and realize how many people contributed to the glorious absurdity of it.

What is The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown if not a product of dozens and dozens of skilled creators who all thought to themselves, “yeah, this will work”?

It does work. It is a great time. It is also a little bit about Stockholm Syndrome. But, mostly, it is about Jane Russell being tall and wearing hats and having absolute control over her image for one glorious film.

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 11/07/2021.

-Meg

A Robert Donat Monologue For Every Wistful Occasion

Robert Donat is the monologue god. No one can touch him when it comes to staring plaintively off into the middle distance–the weight of eternity on his shoulders. The understanding of the fragility of human life fueling his insistence to go on–to keep on living.

Robert Donat is the monologue god. No one can touch him when it comes to staring plaintively off into the middle distance–the weight of eternity on his shoulders. The understanding of the fragility of human life fueling his insistence to go on–to keep on living.

Here I have compiled a few helpful Donat monologues to help us understand our own feelings and ultimately our own humanity and the purpose of our existence (not all of them are actual monologues strictly speaking please do not @ me).

For when you’re burnt out at work, and really in that surviving not thriving mode, listen to Robert Donat in the clip in the header via Vacation from Marriage (1945) tell you about the groove being comfortable, but yikes so is the grave:

For those times when you’re isolating because of a COVID scare, or just trying to make it through the darkest days of winter, check out Robert Donat having a literal freakout in Knight Without Armour (1937):

When the call of the void is calling you, nothing for it but Donat in The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933):

When it is time to eat the idle rich, we channel Robert Donat’s impassioned impromptu campaign speech in The 39 Steps (1935). Richard Hannay is my first and truest love and inspiration:

For those times you must hold equal, yet seemingly opposing truths together in balanced tension, because life is not simple but it is always true that human beings do matter and war, violence, and empire is always senseless, Mr. Chips announcing the deaths of two people he held dear in Goodbye, Mr Chips (1939):

For when you watch a sublime film and are overcome by your sheer love for the very medium of cinema and all that it gives us each and every day, here comes Robert Donat in The Magic Box (1951) literally sobbing about it to an awestruck Laurence Olivier who will never understand like Donat does the power of film because Donat won the Best Actor Oscar in 1939 instead of Olivier and that’s because Donat feels and the world feels with him:

Robert Donat on film understood how to express loneliness and yearning in such formidable delicacy. Such a stunning presence, and such a beautiful voice to express the fears and hopes of humanity. I will never grow tire of his earnest efforts, and I will watch his films and cry thank you very much.

[Insert Donat Magic Box monologue but it is me weeping about Donat cinema monologues]

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 03/02/2022.

-Meg

QUIZ: Who is Your Classic Film Character Summer Fling?

I love a personality quiz. When I was a kid, I lived for the quizzes in my American Girl magazines. Which kind of dog are you? What famous female athlete are you? What kind of cheese are you? It did not matter. I wanted to answer the questions, and then proudly know that I was unique. I was not like other girls. I was a border collie (as true now as it was then).

We’ve reached the highpoint of summer. Heat domes all over the place. Honestly, too much sun, if you ask me. (No thank you, sun. I’m good.) The time is right to kick back with a cold beverage and take my little quiz and learn who your perfect classic film summer fling is going to be (oooooooh)....from the 7 options I am giving you (to be frank, they were the ones top o’ my mind, and all delightful characters).

Here is how it’s going to work: as you go, write down the number of your answer to each question, and at the end, add up your answers to find your perfect partner for this season. Aka if you answer mostly 1s, then 1 is your summer fling or mostly 5s, etc. I have included an answer key at the bottom. If you’re more love ‘em and leave ‘em, then consider a ranked choice system to come up with your top three beaus!

QUESTION ONE: It’s summertime! It’s time to take a holiday. You’ve been working hard, and you deserve a break. Your ideal vacation is______.

1. Kicking it back in an Italian villa. You like to spend your time in luxury, and you are not looking to do much else but chill out. Maybe a vespa ride around the countryside or a dance here or there, but mostly you like lounging out in the sun.

2. Taking a trip on a sailboat. You don’t even mind working as crew–you just want to get out there on the waves and experience that freedom that only the open ocean can provide.

3. Staycation! You live in the big city, and you enjoy your life. There is always something new to do, or explore. You do not need to go anywhere to relax.

4. Nothing planned. You are all about spontaneity. You pick a new place to visit and just go exploring. You are sure you will find an adventure.

5. Not a family vacation! You are trying to get away from your family, not spend more time with them.

6. On a train. You love to travel by train and stop off along the way throughout the countryside and little towns. Hiking, running, scrambling over rocks–anything that gets you outside and active.

7. VACATION? Who has time for vacation? You do not. You have things to accomplish, and nothing else matters.

QUESTIONS TWO: Ahh food! There are few things better in the world than sitting down to eat your perfect meal. The food you crave most is____.

1. Italian food paired with a perfect wine.

2. Well, food does not really satisfy you in itself–but you love an experience. You have always wanted to have a real picnic!

3. This little Japanese restaurant down the street that has an incredible, authentic menu.

4. Whatever food is right in front of you! You love to feast and feast and feast. You keep snacks next to your bed–just in case–and a jar of pickles is never unwelcome.

5. A home-cooked meal from someone you love. It does not matter what it is, it is worth all your money.

6. Simple fare. Anything that is easy to find along the road. You love a sandwich.

7. FOOD? Who has time for food? You do not. You have things to accomplish, and nothing else matters.

QUESTION THREE: What is the most played song on your playlist?

1. "Mambo Italiano" by Rosemary Clooney

2. "bad guy" by Billie Eilish

3. Anything new and avant-garde.

4. "I Love It" by Icona Pop

5. "I’m On Fire" by Bruce Springsteen

6. "Run for Your Life" by The Beatles

7. You don’t listen to much music, but you love to sing. People always know you’re around when they can hear you singing.

QUESTION FOUR: What was your favorite game to play when you were a kid?

1. Musical Chairs. You love group games, dancing, and making sure everyone is having a good time.

2. Wink Murder. No one ever guessed it was you even though you drew the murderer card every time.

3. Anything you could make a bet on. You knew how to win and make money from a young age.

4. Games with rules are boring. And don’t even get you started on board games: you get tired of them easily and tend to flip the board!

5. Spin the Bottle. hehe.

6. Hide and Seek. You were always the best.

7. Clue. You are clever, patient, and determined. You always found the murderer.

QUESTION FIVE: What is your favorite animal?

1. Definitely not parakeets.

2. Sharks. You saw a group of sharks attack an injured shark once and have never forgotten the spectacular sight.

3. Anything wild and free. No domesticated cats.

4. Honey Bees. You're here for a good time, not a long time.

5. Geese. When you've found the right partner, you're in it for life.

6. Foxes. You love their cozy little hidden dens.

7. A lone wolf. You admire their ability to track and hunt.

QUESTION SIX: What is your greatest fear?

1. Not being taken seriously.

2. Not getting to see the sunrise one last time.

3. Getting trapped.

4. Being bored and/or running out of snacks.

5. Being disrespected.

6. Someone telling lies about you.

7. Not fulfilling your purpose in life.

QUESTION SEVEN: You’ve been shipwrecked and stranded on a desert island, but you managed to carry two items with you from the sinking boat that you knew you needed to survive. Those items are_____.

1. A portable two-way radio and signal flags.

2. A knife and a gun.

3. An inflatable lifeboat and a compass.

4. A pair of scissors and a large jar of pickles.

5. Flint and a first aid kit.

6. A tarp for shelter and a machete to cut open coconuts. I guess you live here now.

7. Does it matter? You’ll figure a way out.

QUESTION EIGHT: Your favorite way to interact with other people online is___.

1. You are on every app at all times and have literally thousands of devoted fans, errr, friends.

2. Twitter. It is both the source of your sickness and its only antidote.

3. LinkedIn. Professional use only. The real life is happening offline.

4. Tumblr, baby! You know how to curate!

5. Exchanging numbers with your Tinder matches and then texting for 12 hours straight.

6. Signal messaging via burner phones only please.

7. You do not really have time for this, but okay, you sometimes post cryptic yet wistful poetry on your old LiveJournal. It reminds you of a different time when you were younger and happier.

ANSWER KEY

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 1's....

Your summer fling is Lisa Fellini as played by Gina Lollobrigida in Come September (1961). You are fun and flirty and a great communicator. You love to socialize and everyone sees you as the life of the party. You know what you want and you have great boundaries. Enjoy riding that vespa around the Italian Coast with the most beautiful woman in Italy. She demands respect, honesty, and commitment–so do not mess this up!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 2's....

Your summer fling is Elsa Bannister as played by Rita Hayworth in The Lady from Shanghai (1947). The people that know you would say that you are intense. But they also cannot look away from your allure. You are mesmerizing and totally misunderstood (but also a little evil, sorry!). Your cynicism is a good match for Elsa, and you both are not expecting more than you can offer. You and Elsa are either going to have a great summer or immediately break up. Hard to say, but it will be a wild ride while it lasts! Good luck!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 3's....

Your summer fling is Jack Parks as played by Sidney Poitier in For Love of Ivy (1968). You are independent and reliable, and undeniably cool. You know all the best places to eat and hang out. You live in the city and you love it at every hour–day and night. Just like Jack, your community is important to you, and you work hard to make sure the people around you are taken care of each day. You and Jack are both not looking to settle down…or are you?

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 4's....

Your summer fling is Marie I and Marie II as played by Jitka Cerhová and Ivana Karbanová in Daisies (1966). You are chaotic, unpredictable, and totally vibrant! You are not big on plans and love to take each day as it comes. You deeply understand the futility of society and choose your own path of joyful nihilism. You absolutely do not like to be left alone for any amount of time, and neither do the Maries! Get ready for a summer of feasting, snacking, and decadent food fights. Grab a baguette and jump in–the milk bath temp is wonderful!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 5's....

Your summer fling is Clara Varner and Ben Quick as played by Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman in The Long, Hot Summer (1958). You’re intense and focused, but also a hopeless romantic. You have high standards and a great deal of self respect. You are not going to settle for anything less than the best, but once you have your sights on the best–watch out! Clara and Ben saw you from across the bar and liked your vibe…

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 6's....

Your summer fling is Richard Hannay as played by Robert Donat in The 39 Steps (1934). Frankly, you have a lot going on. You are a busy person always on the go, go, go. A natural traveler, you feel comfortable in every situation and circumstance and you make friends easily. There is nothing quite like a scramble over the rocks or a walk through the moors, and you do well outdoors. Although incredibly likable and adaptable, you and Richard both tend to hide your true selves and have trouble trusting other people. This may make your relationship a short-lived one, but if you can find a way to let each other in–maybe you go the distance together!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 7's....

Your summer fling is Tetsuya "Phoenix Tetsu" Hondo as played by Tetsuya Watari in Tokyo Drifter (1966). You do not have time for a relationship, as you are all-consumingly focused on your life’s mission. Everything else fades in the background. You must complete your task; you must fulfill your purpose. You are lonely, and although you might sometimes seem like a hard-hearted island of a person, you are actually very tender and gentle in your soul. There is a real softness about you, and if you could just be free of your work–free of your drive–you know that you would choose a very different life. Tetsu is on a parallel path as you, and together maybe you finally accomplish that

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 08/11/2022.

-Meg

Steve McQueen, Cinema Goofball

Popular culture remembers Steve McQueen as the King of Cool, a paragon of stoic masculinity, a laconic man of few words and fewer emotions. But, what of the other side of Steve McQueen’s on-screen persona?

Popular culture remembers Steve McQueen as the King of Cool, a paragon of stoic masculinity, a laconic man of few words and fewer emotions. The remembered idea of him is two-dimensional, and–as a marketing scheme–highly successful: his name appears regularly in the lists of the most profitable dead celebrities. He is an image: stern, unflinching, immovable, untouchable. He doesn’t crack under any pressure, just like a Tag Heuer watch. He is “The Absolute Man” according to the vodka brand.

But, what of the other side of Steve McQueen’s on-screen persona? Not the vroom-vroom car chases and cool sunglasses and dialogue-free scripts. Not the decades of co-optive advertising. The other side: the much-maligned (but much-beloved-by-me), entirely uncontained, earnestly unsure total goofball.

I came to Steve McQueen early in life. He is my oldest brother’s favorite. Five years older than me, this brother always had a Steve McQueen movie playing, or a DVD lying about. My understanding of McQueen was formed first by the television series Wanted: Dead or Alive. And yes, he does play a cool loner bounty hunter traveling through the American settler west of the 1870s. But, his Josh Randall is also deeply connected to the people he meets along his travels, always getting involved, solving troubles, and occasionally forced into absolutely wacky shenanigans.

Burned into my memory, is an episode from the final season released in 1961, titled “Baa-Baa.” Josh Randall is sent in search of a lost pet sheep, there’s a singing chorus, montages of him chasing sheep over hills, and pratfall face grimace combinations not seen since the days of Cary Grant flying through Arsenic and Old Lace. That is my enduring image of Steve McQueen: flailing and just a little earnest.

I have written bits and pieces before about Steve McQueen’s depiction of masculinity. It fascinates me. It never seems to me to be the confident, unbreakable idea that endures from his most famous roles, but in actuality rather fractured and unsure, as if he was precariously holding himself together. Often the only outlet of emotions in these performances is violence. Once stardom took hold, there was an increasing unwillingness on-screen to divert from tightly-contained emotions and limited dialogue; almost as if to open himself up at all would be the end of his control.

This is a marked difference from some of the other enduring cool guys of the era, like Sidney Poitier, Toshiro Mifune, or James Garner. Their self-confidence felt entirely real and fully true to themselves in every kind of film or performance. James Garner was good pals with Steve McQueen, but also had this to say in The Garner Files, “He was a movie star, a poser who cultivated the image of a macho man. Steve wasn’t a bad guy; I think he was just insecure. … Deep down, he was just a wild kid. I think he thought of me as an older brother, and I guess I thought of him as a younger brother. A delinquent younger brother.” (Note: This is also what happens when you put two Aries together, I say as an Aries.)

That delinquent younger brother energy is a dominant theme in all of Steve McQueen’s “b-side” films: those films that do not comfortably fit into his steely iconography, and are left out of all the advertising and the cool montages.

Steve McQueen’s best performance comes in one of these films, Love with the Proper Stranger (1963). A romantic drama permeated with sweetness, it is McQueen’s softest role. His co-star Natalie Wood is glorious, confident, and self-assured even while her character is facing extraordinary fears and pressures. McQueen plays his character hesitant and awkward. He is a cool-cat jazz musician who trips over and mumbles his words and hunches and slouches his body. The finale of the film is the ultimate goofball gesture–and stunningly earnest.

Sometimes, Steve McQueen’s ventures into goofball territory are far less earnest. The Reivers (1969) is a film I would charitably describe as YIKES (but what a supporting cast! Rupert Crosse! The great Juano Hernández!). It is also a strange amalgamation of his competing film energies. There is the obsession with a car and emotions processed via violence (particularly directed at women), but there is also slapstick slipping in the mud and very big reaction faces. There is an internal battle for his performance soul warring throughout this film, and violent goofball is not really a comfortable spot to land.

Critical and public appraisal of McQueen’s ventures outside his narrow sphere has never been laudatory. Anything he did that came close to comedy has been thrown out in confusion with a note that it is “really not his thing.” Yet the problem with The Reivers is not the earnest comedy, but the elements of coldness and violence. Steve McQueen’s image sells luxurious watches under the promise that he doesn’t crack under pressure. Ice cold silence sells. Flailing limbs and high-pitched scrambling does not sell vodka--apparently!

Yes, the time has finally come to talk about The Honeymoon Machine (1961). This movie is bonkers, but with that impeccable internal logic that makes 1960s comedies run so smoothly in their own wild realities. It is also peak goofball McQueen. As a scheming sailor with a plan to game the roulette wheel in a Venice casino using a naval computer, he talks extraordinarily fast–often at a high-pitched squeak–and says more words than most of his other films all put together. He stumbles and trips and sways. He is a delight. He hated it.

He walked out of the first preview, and said he would never work with MGM again.

I think it is one of the most endearing McQueen performances. To watch him play a James Garner comedy role without James Garner levels of self-assurance is such a feat of sincere effort. He pulls it off too, because it is all McQueen. He may be playing a zany goofball, but the threat of violence feels ever-possible as he hops about manipulating everyone around him and talking about Nietzsche.

I love Steve McQueen’s on-screen work. 12-year-old me somewhat unconsciously attempted to model my stride on his after watching that long opening shot of him walking down the street in The Cincinnati Kid. His Vin in The Magnificent Seven is one of my favorite characters dear to my heart. His work as Sweater Detective in Bullitt is an aesthetic triumph. Wanted Dead or Alive fills my soul with joy (and I once wrote a piece about its fashion when I was 17). That episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents where he bet Peter Lorre his finger is a lesson in building tension in 25 minutes (I also love that episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents where he is a goofball Martian).

But, my understanding of Steve McQueen is not an image used to sell watches and vodka and cars. My Steve McQueen does sometimes crack under pressure. Sometimes, Steve McQueen was bold, violent, cold, angry, and harsh–causing pain that ripples. Sometimes, Steve McQueen was fractured, unsure, flailing, earnest–looking for a safe route to just be. Sincerity even in its tiniest measure is a hard-won human triumph! Long live the sincere goofball cinema of Steve McQueen! (Maybe don’t watch Soldier in the Rain though.)

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 01/10/2022.

-Meg

Bikini Beach (1964) or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Embrace Joyful Nihilism

Bikini Beach // dir. William Asher // United States

Bikini Beach // dir. William Asher // United States

We have had more than one successive day of sunshine here in Seattle, so yes, I am calling it: SUMMER IS HERE! As with many things in life (I resisted adding a heavily sighing “these days”), summer is more of a vibe than an actual tangible construct. So, to celebrate that, I want to celebrate a film that truly understands why vibes are more important than tangible constructs.

Bikini Beach (1964), dir. William Asher, is basically the third in a nebulously numbered series of Beach Party films (whatever the true number of films in the collection is--I’ve seen them all), and it is also the best film of the entire series.

(Quick vibe-check: if you think the best Beach Party film is Beach Blanket Bingo, respectfully, please either keep that to yourself, or quietly exit today’s lecture--thank you!)

Its status as best is perhaps based entirely on the initial determination of my 14-year-old self, but I truly do trust that 14-year-old me remains the best judge of 1960s teen surfer comedies, so we are running with it.

14-year-old me is also where our story begins today, as that was my age upon first viewing this cinema treasure. It was 2008, and back then, Hulu used to have an entire library of ~underappreciated~ 1960s movies to watch for free without subscribing (reach out to discuss Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine at length anytime). I saw this, and quickly showed my childhood best friend and it entered the sleepover rotation, and the rest is history, and I am definitely going to text her “Oooh Bixby’s Bird Farm!” as soon as I am done typing this up--and she will immediately get it.

There is something to the fact that all these films were made by American International Pictures (all hail cinema) very quickly and very cheaply and intended to be direct-to-the-teens movies, and somehow that strategy was still holding up and working out forty-five years later.

The formula works, because it is basically all bright colors, sight gags, and occasional footage of stunt surfers wearing visibly fake Annette wigs. More to the point, the formula works, because Annette Funicello + Frankie Avalon really are fun and charming onscreen. Their performances are truly enjoyable, and they have sweet, friendly chemistry together (I am not the first to say this, obviously, but consider it very Doris Day + Rock Hudson in the best ways).

In this film (and others in the series), Annette Funicello has the often thankless role of trying to get Frankie to think about his future, but she does so with a mischievous twinkle and a strong presence. She also really knows how to sing softly+sweetly while walking on a rear-projection beach at night-time, and I am not being ironic by saying that. It is an actual skill to inject so much personality and professionalism into formulaic, low-budget films. Plus, I have never stopped thinking about these pants.

And, Frankie Avalon in Bikini Beach? Well, let’s just look at the first note I scratched out while considering what I wanted to write here: “Tour de force Frankie Avalon the only good teen boy 60s actor.”

Those who know me well, will know that while I do enjoy frequently saying the phrase tour de force out loud, I do tend to truly reserve it as a description for work like Paul Robeson in Body & Soul, or Irene Dunne in The Awful Truth, or Tom Hardy in Venom. So, when I say Frankie Avalon’s dual role (!!!) as Frankie and as The Potato Bug is tour de force, I truly mean tour DE force. On that note, what I am about to tell you is going to make you reconsider trusting 14-year-old me as a cinematic arbitrator, but actually it should just reinforce the objectively career-pinnacle work Frankie Avalon does here.