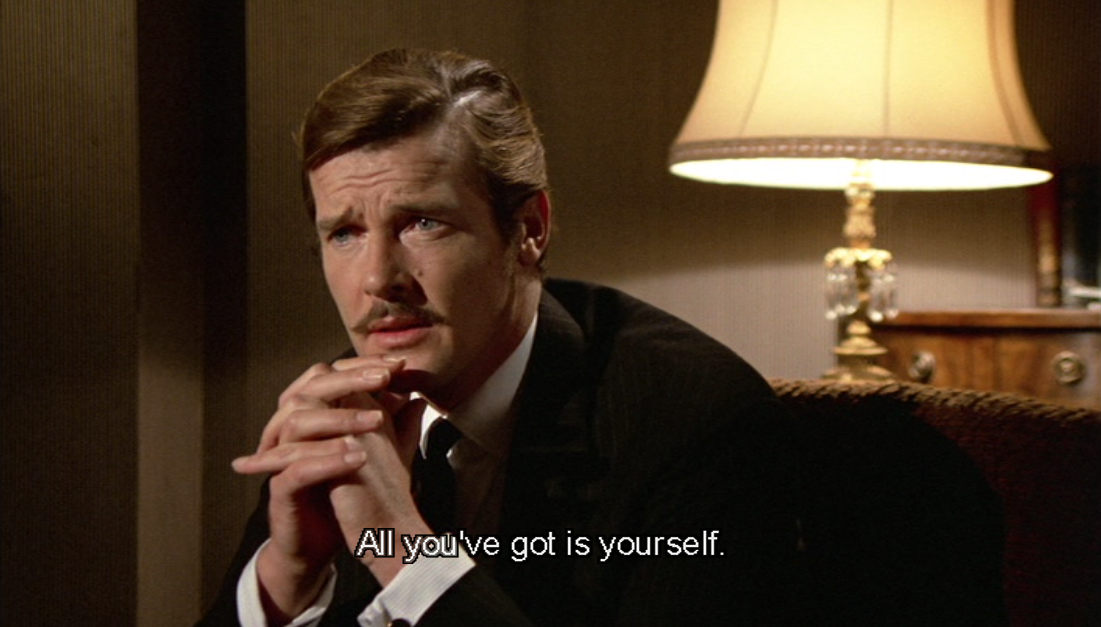

The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970)

The Man Who Haunted Himself // dir. Basil Dearden // United Kingdom

Do you ever just know you’ll love a movie so much that you cannot even bring yourself to watch it? Not because you’re worried about being disappointed, but because you’re worried that you’ll truly love it too much. You’re worried that you’ll just feel too much?

Well, yes, I must say that is exactly how I felt about The Man Who Haunted Himself. I truly cannot remember where I first read about it, but it was in a book about movies and it was given a page with a single image. I was probably 12 or 13. I remember the entry was oddly dismissive. It vaguely explained that it was a rare and singular serious performance from Roger Moore, but it was not financially successful and was perhaps best forgotten.

Of course, that merely fueled my need to see the movie.

Roger Moore’s Simon Templar and I go way back. We’re pals. (The first car I ever drove—a vehicle that truly ran on pure force of will and literally a taped-together exhaust pipe—was affectionately named Simon.) I needed to see this film.

It was impossible to find.

It stayed a low hum on an ever-growing idiosyncratic list of films I NEED to see for one reason or another.

And then, eventually, Kino Lorber put out a release, and I gobbled up a copy last year.

But, I just couldn’t bring myself to watch it. I had waited too long. I instinctively knew I would love it, and what if I just loved it too much? Living alone a year into a pandemic lockdown is enough to make anyone worry that a pitch-perfect Roger Moore performance in a 50-year-old film is enough to break apart the loosely patched seal enclosing my deepest human feelings. Right?

Anyway, my old pal and partner-in-1960s-ITV-shenanigans Emm suggested watching it together this evening over video call and it was just the nudge I needed.

I almost cried before the film had even started, because I was thinking about how much I love cinema. WE’RE DOING GREAT OVER HERE.

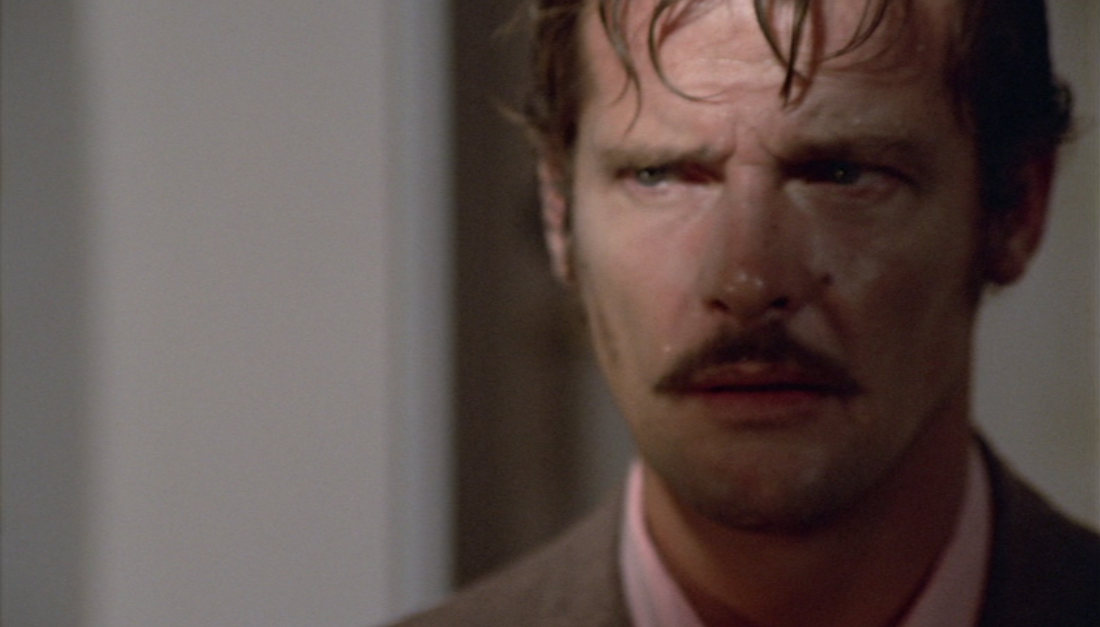

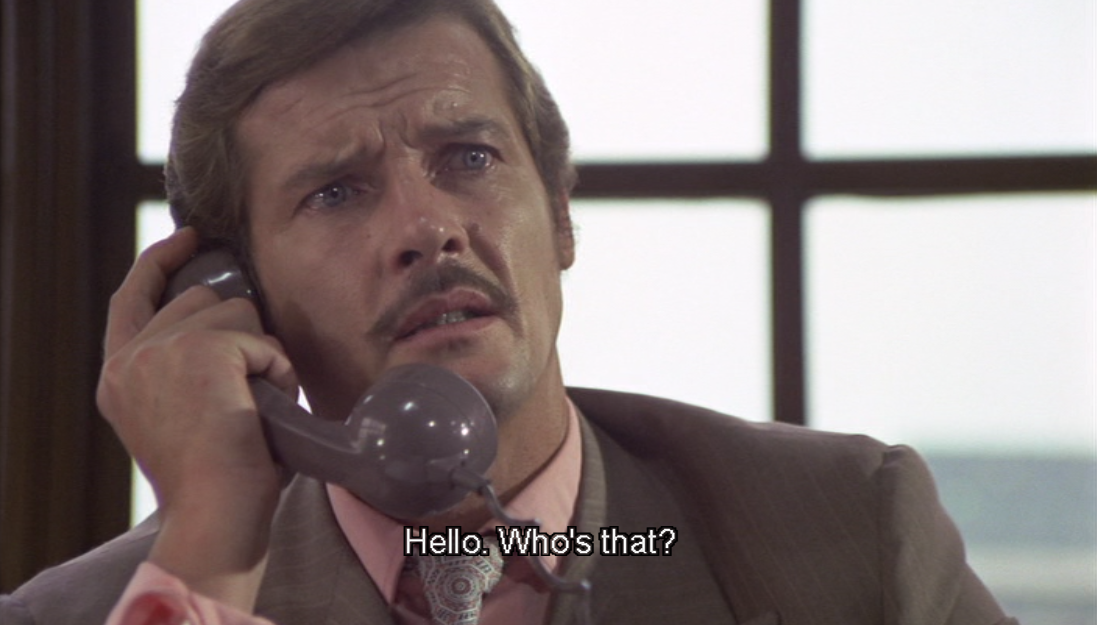

Roger Moore plays Pel with such control and with such internalized emotion: be it self-loathing or exhaustion. His inhibitions reign. His façade of success hides an increasingly-apparent sense of isolation. As the film goes on, he becomes less sure of himself—and Moore plays that so acutely and so naturally, it’s astonishing.

So natural does he fit that when we see Moore play another version of Pelham—a charming, confident, self-assured, swaggering version with quick lines and quick smirks ala Simon Templar (or even Roger Moore’s own public persona)—it immediately reads as false; as diabolical.

This film pries open the unstoppable Roger Moore-like persona to focus on a vulnerable, unsteady character who lives only in others’ perceptions of him. He looks in mirrors wondering what they see.

This was Roger Moore’s personal favorite performance and film, yet it was not financially successful. He played vulnerable for the screen, and it was rejected. Lesson learned: he almost immediately went on to play James Bond for the next 100 years.

He was always dismissive of his own acting and talents. He claimed to have never received any critical praise for his own abilities. His success was based on the effectiveness of raising one eyebrow or the other. But, in the midst of the self-deprecation, he always had a word of earnest pride for his work in this film.

“It was a film I actually got to act in, rather than just being all white teeth and flippant and heroic.”

I suppose that is what (ahem) haunts me most about this film: it is a story driven by personal identity and the fear of being wholly oneself, yet the person who cared the most about the film spent the rest of his life feeling his work in it had never reached its audience.

Look, yes, I am going wild on my reading of this film, but that’s cinemaahh, baby. My ability to see earnest effort and vulnerability inside the most technically unexpected places is literally undefeated. (Also, everything written previous to this sentence was written late at night right after I watched the film, and the rest of this was written on a sunny afternoon two days later.) I can and will go on. But, first let’s talk about this scene that eerily and accurately describes how it feels to watch YouTube late at night when you cannot sleep.

^That’s just ASMR, baby!

(I have picked up saying “baby” in a really exaggerated way—primarily blaming aforementioned YouTube and particularly clips of James Acaster saying anything—and I am genuinely distressed to see it has migrated to my writing. But my writing style is conversational, so I am sorry to say I cannot delete the “baaabys” when they appear. It would be artistically unethical.)

Now that I have got my earnest emotional rush out of the way (and I cannot promise it won’t return at any moment), I really want to talk about the glorious aesthetics of this film. Because that is how you reach me: characters expressing inner turmoil+vulnerability with cool camera angles and maybe some fun neon lighting if we deserve it.

This film took it a step further. Basil said, yes, you deserve fun neon lighting! Lads, let’s give ‘em bisexual lighting while Roger Moore has an emotional breakdown driving a car in a rainstorm! We love to see it. :’)

The style of this is film is utterly and precisely and specifically a 1970 release—she’s delicious!

Each of the characters, not just Roger Moore’s Pel, are very interested in the way they visually present themselves to others. We see the art in the homes, we see the individual wardrobes and closets, we see the specific care put into hairstyles, and we even see the way characters pose and position themselves for effect.

Even the psychiatrist wears an intriguing pair of dark lenses indoors—contrasting with the slouchy look of his clothing.

The film concerns itself with unfulfillment, and while there is a somewhat plastic, shallow 1970 sheen cast upon it, there is also a uniqueness and a depth to each of the characters. Certainly, Pelham’s sense of self experiences fluctuations that Roger Moore plays with honestly a beautifully precise touch.

Hildegarde Neil plays Eve Pelham, Pel’s wife, with a level of malaise that hits perfectly. She is trapped in the same patterns and outcomes: all of which are unfulfilling. She does, however, present herself perfectly to the world and to her husband: it is one of the efforts she makes to break the patterns—to rise to the occasion. She is incredible.

Also, this gown is uhh v. dreamy.

Since I have taken a detour into clothing, let me now talk about Olga Georges-Picot. She also elevates the truly minor “random, mysterious woman required by script convenience to mostly lounge about in untied robes” character beats she is given. I was intrigued by her. I wanted to know more. She played the straight man to Pel’s shattering breaks in reality, but crucially, I always got the sense her Julie had a life that continued when she wasn’t onscreen dealing with that man haunting himself.

ALSO LOOK AT THIS ICONIC LOOK.

I—well—

okay, friend! love the way you present yourself to the world. love those paper flowers on the wall especially! fun!

Julie is the only person I felt like, “She’ll be fine.” And that’s truly an accomplishment as a secondary female character in a 1970 psychological horror production. I say without irony, GOOD FOR HER.

I need to end this post, because honestly soon it will devolve into me eventually just listing every lighting choice that I felt in my cinematic soul or something.

I really just want you watch it—and then leave me a comment, so we can start an email correspondence subject line: ROGER MOORE’S TORTURED FACIAL EXPRESSIONS.

When you get down to it, the reason I felt so deeply emotional about this (unfairly) forgotten film is because of the parasocial bond I developed toward Roger Moore when I was at my most impressionable age. I have actually never seen any of his Bond films (in the reverse of the opening premise of this post in that it’s a case of knowing I will hate a movie so much I don’t ever want to see it and feel too much), but as mentioned before—I adored his Simon Templar.

I grew up in an isolated circumstance, and did not have very much meaningful interaction with people outside of my family or the world outside a limited set of places. I felt constantly unsure of myself, and my place in the world. I was labeled a shy child, but I wasn’t. I was just a child without the safety to be fully myself—confident in myself—confident to know myself.

enter film and tv (mostly only films made during the Hays code [lol], and TV from the ‘50s/’60s).

Send the scientists to visit little Meg for some textbook parasocial relationships.

I had an entire pantheon of my people: the characters and actors and performers I sought to steal a little bit of something from—or maybe use as a Rosetta stone for my own already existing identity.

From Simon Templar, I saw confidence, an understanding of the absurdity of life, and the vague notion that one must be of service to others to live (to be sure, Templar’s level of service is highly dubious and highly errr self-serving). Simon Templar was fun and had a good time and always knew who he was in every circumstance or relationship. He was also taller than everyone else. None of these things transferred so easily or exactly.

This should say enough to see a glimmer of why Meg in her late ‘20s (just truly crossed that threshold two hours ago) would get so emotional about a film starring Roger Moore actively fighting his own persona of confidence to express an absolute confusion about himself.

mamma mia! I didn’t want to feel this much! </3

Anyone, please enjoy this below prescription that is also exactly what I’ll be doing when I get that second vaccine dose!

I also want to note that early into this screening, Emm suggested that Roger Moore would have been an iconic casting choice for Sir Percy in The Scarlet Pimpernel (a childhood favorite book for reasons which are probably odiously obvious), and I honestly will never forgive her for putting that idea out there knowing I can never have it. boooooo!