The Sinister Fun of Bradford Dillman

“By my reckoning, in over four decades I’ve been personally responsible for the demise of well over a thousand people. Heck, at Jonestown alone my Kool-Aid took out over nine hundred, and I’ve blown up the Queen Mary twice. Heroes are heroes. They pay the single greatest price of celebrity, the loss of privacy. This explains the army of bodyguards employed by some to keep the adoring multitudes at bay. Villains don’t have these problems. Me, I’ve never been bothered in a bar or boite. People can’t be sure I’m not carrying a knife or a gun.”

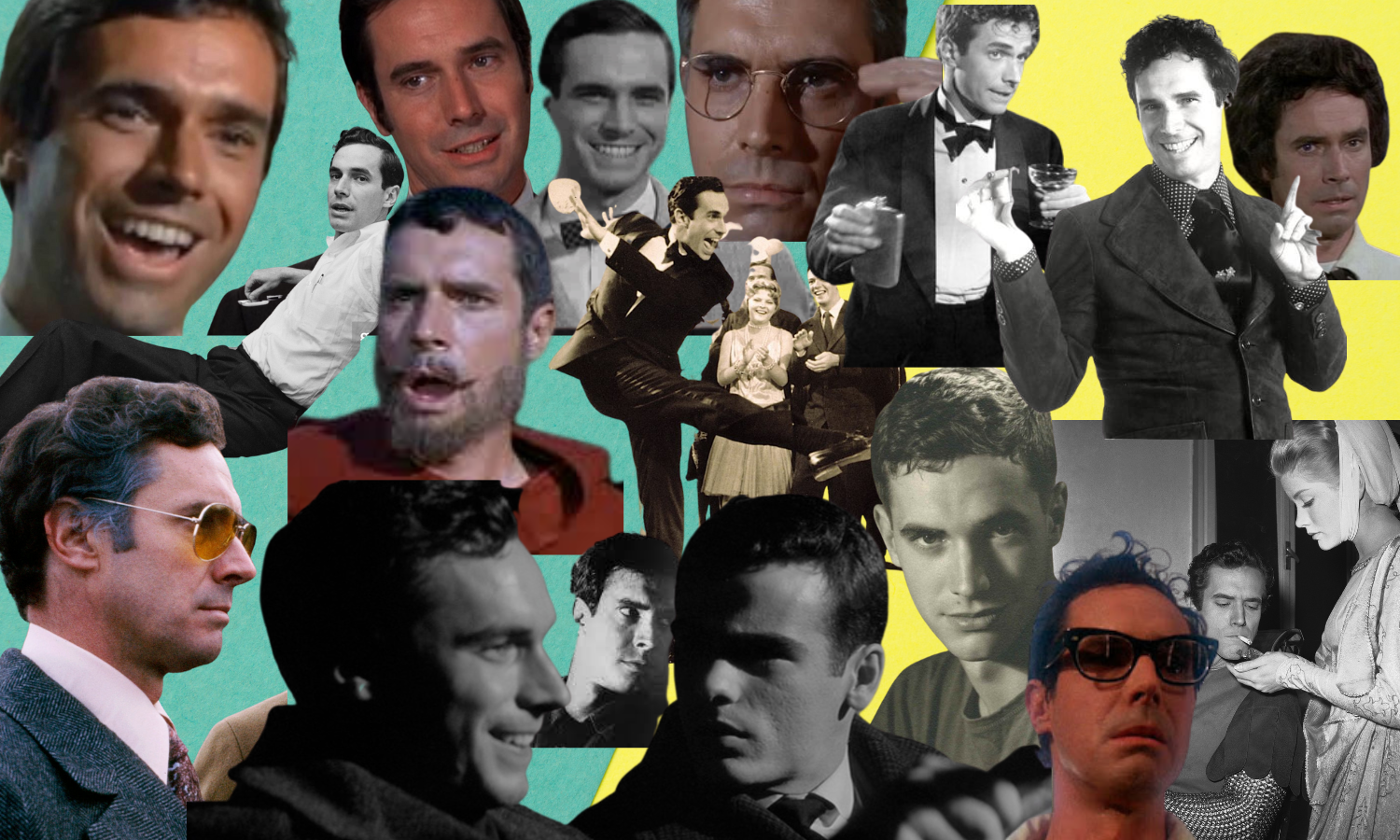

It is April, the sun is shining, and life is returning to some of our weary bones after what can only be described as a long, harsh winter of total discontent. In short, it’s Aries season, friends; and there is no better time to talk about charismatic villainous virtuoso Bradford Dillman (who would have turned 91 this April 14th). Bradford Dillman was an omnipresent actor in Hollywood for decades with a range that took him from The Actors Studio--debuting on stage with James Dean--and originating the role of Edmund Tyrone in the Broadway production of Long Day’s Journey Into Night to creature-feature horror and endless guest-starring roles attempting to kill the heroes in seemingly every 1960s and 1970s television program. He also kissed an ape in Escape From the Planet of the Apes.

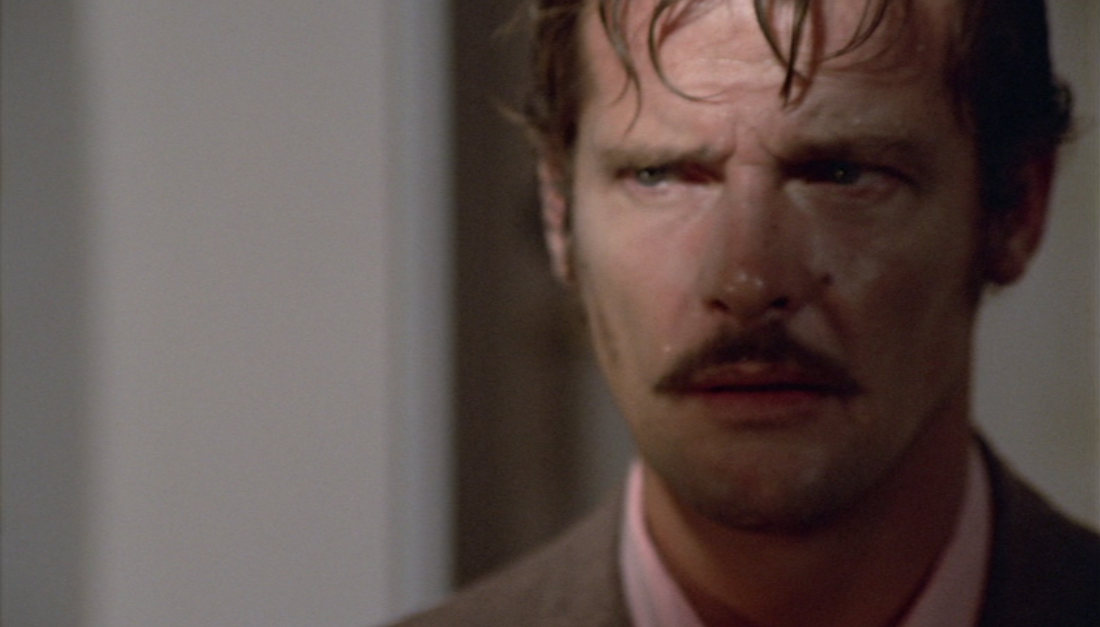

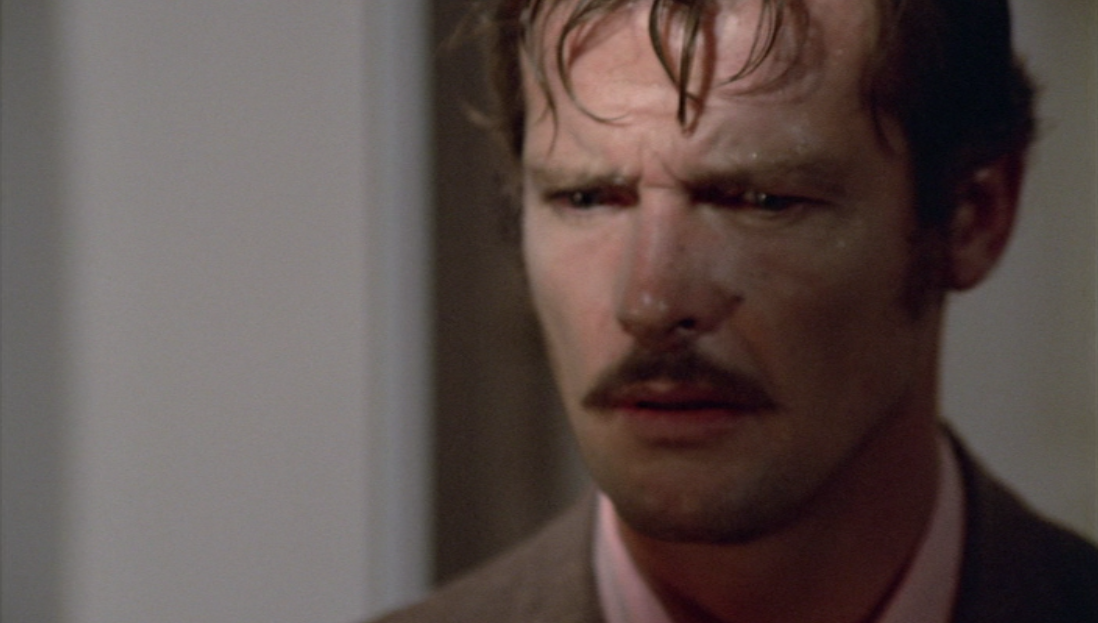

Bradford Dillman is an heir to Peter Lorre and predecessor to Michael Shannon in the spectrum of actors giving us high-caliber sinister charm all mixed up with genuine emotional connection. He had the best evil smile in the business: a bent, slightly twisted smile that promised chaos--or at the very least some premeditated malice. His presence filled up all the empty spaces in every medium he appeared. A particular maximalist specialty of Dillman’s was the extended close-up on his face as it moved through dichotomous emotions--joy to rage; sadness to glee. He was acutely aware of movement in his face and body, but at the same time seemed to understand that he was supposed to provide an experience that was not quite human, more like human+. Why go out quietly, when you can go out screaming, howling, and/or cackling?

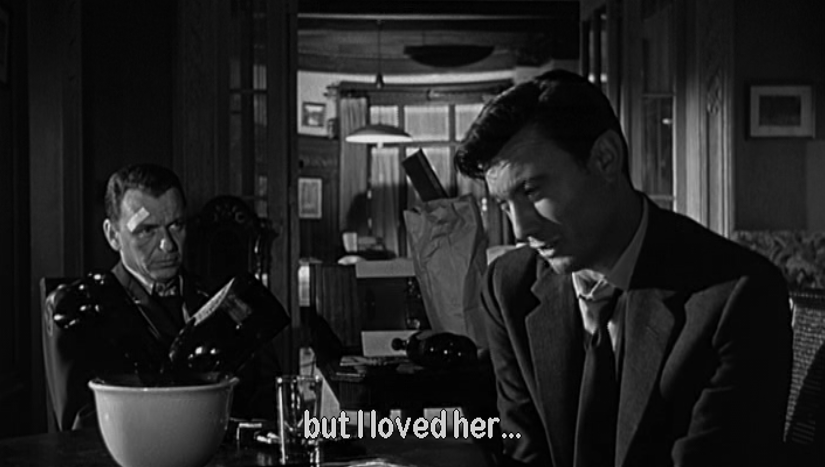

One of his early film roles was in Compulsion (1959), dir. Richard Fleischer, a fictionalized retelling of the Leopold and Loeb murder and trial. He played Artie Strauss (Loeb), a petulant 18-year-old rich boy who has never experienced a single consequence in his life and is convinced of his own superior intellect. He is as terrifying as he is charming, and his dominance over his (boy)friend as played by Dean Stockwell is the kind of performance that does not let you look away from it. Certainly not when he can be found carrying on an entire sinister conversation with a teddy bear. He shared the award for Best Actor at Cannes with co-stars Stockwell and Orson Welles (but not the teddy bear, which was a total snub). Compulsion is a film which is at times ethically dubious (for one, the murdered child is given almost zero consideration), but is at all times a work of performer-first filmmaking that builds a tremendous amount of tension, lets its actors run wild, and also contains a classic Welles’ fake nose (and fake eyebags?).

Dillman began as a method actor in important productions™, but since he and his wife Suzy Parker (supermodel; inspiration for Audrey in Funny Face) had a large family together, after she retired, he pivoted to being what he called a “Safeway actor”--anything to put food on the table. This is where he really shines: leaving a legacy of untrustworthy characters with intoxicating charm in every possible kind of film or television production. He was the man to go to for southern gothic werewolves or cult leaders or egotistical supervillains, and also sad dads or sweet dates-of-the-week for Mary Richards, or if you needed someone to play the nephew getting murdered by Uncle Ray Milland in an episode of Columbo. (My kingdom, my kingdom for an episode of Columbo with Bradford Dillman playing the murderer! Come on, Robert Culp and Jack Cassidy--stop being so greedy!)

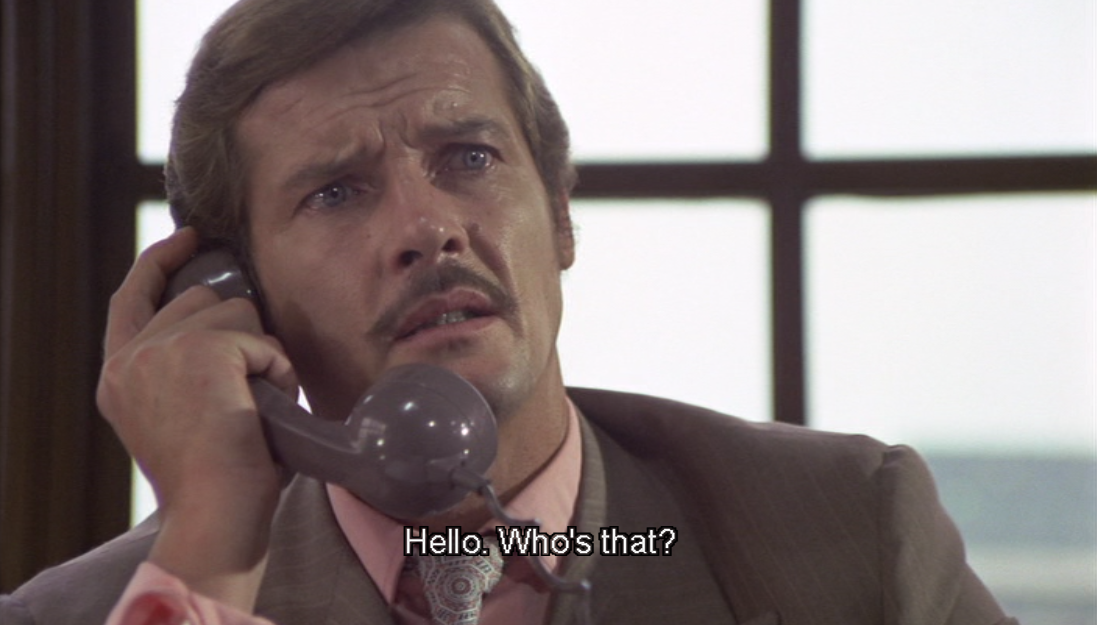

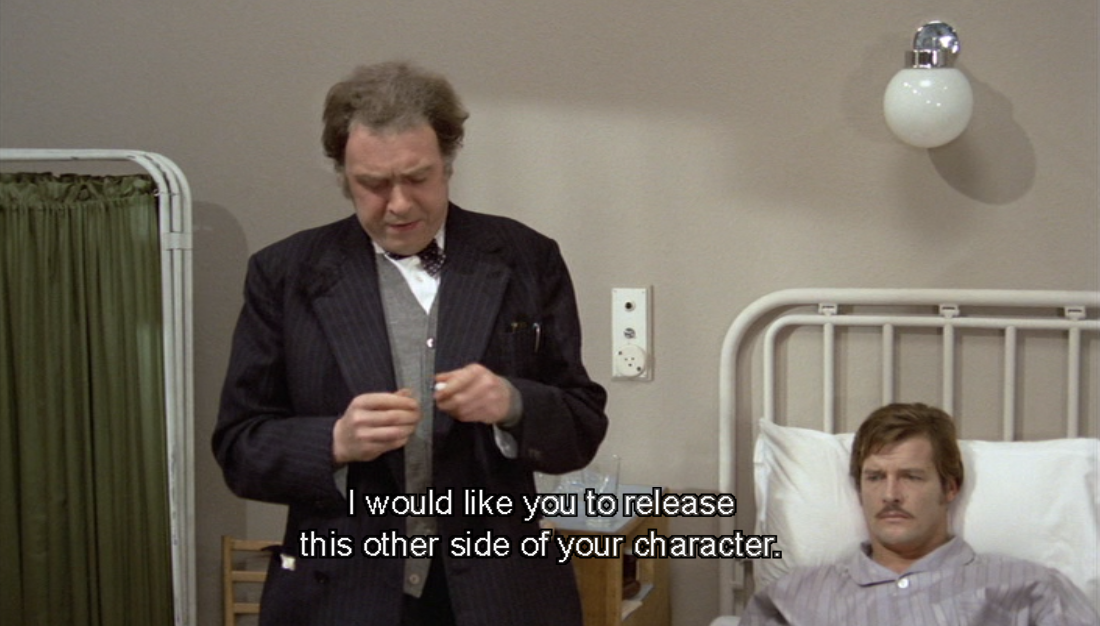

One such unassuming production that got injected with Dillman was Jigsaw (1968), dir. James Goldstone. Jigsaw is a drug-trip murder mystery of uncommon chaos. (One wonders if even the film stock itself was laced with LSD?) It is also total fun, and perhaps even the platonic ideal of a sinister fun Bradford Dillman performance. He plays a repressed, emotionless scientist who wakes up with amnesia, blood on his hands, and in a room with a dead body. Suffice to say, the plot does later require him to trip on acid for ten minutes so he can remember (that’s how it works). The film was shot as a TV movie, but the content was too hot, so it got a theatrical release instead. Bradford Dillman has a great time, and the film plays up his unmatched ability to depict mania. Aside from the unfortunate use of a gruesome murder of a woman as essentially a plot mcguffin, this film offers perfect 1968 colorful+chaotic vibes.

That same year saw a theatrical release of another American television production with The Helicopter Spies (1968), dir. Boris Sagal, a two-part episode of Man From U.N.C.L.E. edited together as a single film for an international theatrical release. It contains an astonishingly fun performance from Dillman as the leader of a cult called The Third Way. Everyone in the cult (aside from him) is forced to dye their hair white blonde to match The High Priestess, while he wears an entirely white outfit (suit, shirt, shoes). Cult members greet each other by saying, “Keep the faith!” while offering a thumbs up. Naturally, he has plans to take over the world, charms absolutely everyone into believing him (including our two heroes), and goes on scamming. Because it is Dillman, we are never quite sure whether he is maliciously scamming for power and using the cult as a means; or whether he is maliciously scamming for power while actually believing in the cult. Delicious!

It is that level of morally unstable character (to borrow a line from The Naked Spur) that makes even supporting performances in films like Five Desperate Women (1971), dir. Ted Post, so much fun. The titular women are Joan Hackett, Stefanie Powers, Anjanette Comer, Denise Nicholas, and Julie Sommars. They are college BFFS reuniting on a private island cabin after five years--and they are a "mess" (some of them don’t even have husbands or babies yikes!). The chemistry between the women is genuinely perfect, and is a great intersection of heartfelt and camp. What we know, but the women do not, is that a murderous man is currently loose in the area. Naturally, our suspicion falls on Bradford Dillman as the boat captain who ferries them over to the island. He is a real weirdo and alienates them all almost immediately by explaining nutrition and how they clearly do not understand health like he understands it. Bradford Dillman keeps us dancing the whole time on the power of his sinister reputation alone.

This reputation for crafting exceptionally twisted...but fun characters (imagine I am saying that in a Sullivan’s Travels-like “with a little sex in it” cadence) kept him employed for decades. One of his final films was the Roger Corman-produced Lords of the Deep (1989), dir. Mary Ann Fisher. Honestly, this film is weird and freaky--and worth it for the wild camera work and special effects alone. It opens with a title card letting us know the year is 2020, and “Man has used up and destroyed most of Earth’s resources.” *gulp* Bradford Dillman is the good company man who commands a huge corporation’s experimental underwater habitat. He is a sinister capitalist who will see everyone dead before losing a drop of profits. He slithers around saying things like, “Are you imPLYING that I would endanger the lives of MY crew?” and “We used to have a thing called an Ozone, Jack. Remember? ... You idiot.” It had been thirty years since Compulsion, and he had not lost an ounce of his ability to terrify and charm in equal measures.

These five films I have picked practically at random, and they do not even begin to touch on the levels of delight to be had in Bradford Dillman’s 40-year, 142-credit film and television career. (These five are all available on streaming, however. I would especially give a look toward searching these titles on YouTube, ahem.) You can choose any one of his 142 performances and find something to shock, awe, and/or entertain you.

And, he certainly did not always play the bad guy (not even in all of these five films), but just as his villainy was multifaceted--his goodness was complicated. Suspicious, dark, twisted and bent like his famous smile. The man knew how to show us a good time.

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 04/05/2021.

-Meg

An Ode to Sandra Dee

Let me paint a picture for you: It’s 2008, and I am 14-years-old, and newly attending a local homeschool co-op that meets every Monday in a church that’s forty minutes from my home. A homeschool co-op is an educational construct in which a bunch of homeschool moms (and it’s always moms) create their own insular school system and then teach the children of the other moms so that the art moms can just focus on art, the theology moms theology, the founding fathers moms the founding fathers, and the one mom who is really good at math tries to explain calculus to a bunch of teens who had taught themselves how to add and subtract and multiply and divide. There is no science mom.

This is as close to a classroom or school setting as I had ever been at the time, and I was delighted by the concept of school supplies at last (oh, how I had coveted those overflowing bins at Target), and naturally, immediately decorated my class folders with photos printed out at the public library. I had a James Dean folder, a Grace Kelly folder, an Audrey Hepburn folder, an Ingrid Bergman folder, and a Sandra Dee folder.

On that first Monday, the teacher-mom for the Sandra Dee folder class (it was something like American Citizenship 101) asked me who was on my folder. I said with enthusiasm, “It’s Sandra Dee!” This was a few months before I started my film blog, and I was eager for any outlet to talk. In a move that prepared me for every internet-splainer to come, teacher-mom responded, “No that isn’t Sandra Dee. Sandra Dee is a character in Grease. ‘Look at me, I’m Sandra Dee…’” (She did not finish the lyric, which clearly was a spectre from her heathen youth, as Grease was not co-op approved.) I was torn between knowing that adults should never be corrected, and also by knowing that, well, it was Sandra Dee on my folder. I went with a mumbled, “This is Sandra Dee, the actress.” Teacher-mom said, “No, you must be confused.”

And that was that. I saw no path to victory, but internal fuming, and going home and turning on my library’s DVD of Gidget (1959, dir. Paul Wendkos) that was on semi-permanent loan to me, and watching Sandra Dee prove all her doubters wrong.

Sandra Dee on-screen always proved her doubters wrong. And it was exactly what I needed. She remains one of my favorite people to return to on film: a friendly cinema companion. Her presence carries a quality, a tangibility, a gravitas that has never been allowed to be attached to her name by critics or public opinion. Lucky then that Sandra Dee did not need permission to be indelible.

She is unmistakable onscreen and entirely irreplaceable. The Gidget sequels are enough to tell you that. I mean, look, I am one of the bigger supporters of Gidget Goes Hawaiian, and yes, I did once tell Carl Reiner that Gidget Goes Hawaiian was a great film to which he responded, “No.” But, Deborah Walley as Gidget is just filling space. (And we do not talk about nor acknowledge Gidget Goes to Rome.)

Sandra Dee’s Gidget is alive, so fully alive. She is energy and enthusiasm and vulnerability and confusion and angst and elasticity. Her triumph in learning to surf feels like an earned triumph and the joy is palpable, and equally her scenes late in the film with Cliff Robertson’s predatory Big Kahuna are genuinely distressing because of her performance and her efforts. While Sandra Dee’s work is often tossed away as light-weight and sterile based on some historical collective false memory, her performance in Gidget should really be considered a direct predecessor to Elsie Fisher’s recent acclaimed work in Eighth Grade (2018). Sandra Dee gave us a realistic vulnerable yet determined teen girl who absolutely triumphs (with the loving support of her teen girl BFF) and teen girl me said, “You love to see it! Can you please ditch Moondoggie though? He is a drag.”

Sandra Dee’s known public image today and her original popularity was definitely predicated on her fulfilling some sort of white wholesome teen girl ideal for a 1950s American audience, but conversely her characters are boundary-crossing troublesome girls and young women. A defining characteristic across so many of her roles is a refusal to conform--in small ways and big.

In The Reluctant Debutante (1958, dir. Vincente Minnelli), only her second film, in the midst of swirling mania, she is the cool one--observing the hysteria with bemusement and maintaining her personal sense of self throughout. She assuredly partners with Kay Kendall and Angela Lansbury with a level of confidence that astounds. Her comic timing is already excellent here, and so is her ability to work ensemble. Her most perfect ensemble obviously being Come September (1961, dir. Robert Mulligan), a film that is surely one of the reasons cinema exists as a visual art medium. Sandra Dee and her tangibility are vital. With all due respect to the blonde youth actresses of the 1960s (I love many of them), how many of them would have the precise energy to match so comfortably on-scene with peak powers Gina Lollobrigida and Rock Hudson? There is a scene in which she psychoanalyzes Hudson that is masterfully funny. Her scenes with Bobby Darin are equal parts tentative and confident; sweet and confused. And with Gina Lollobrigida, she is sincere and kind with immediate rapport. There is no danger of fading into one-half of the obligatory forgettable youth B-couple of the movie--even in the presence of the dazzling Lollobrigida and Hudson.

The other two films in the Sandra Dee-Bobby Darin trilogy are also particular fun--with outlandish plots. In If A Man Answers (1962, dir. Henry Levin), she decides to change Darin’s behaviour with a dog training manual, and in That Funny Feeling (1965, dir. Richard Thorpe) via some classic mistaken identity she convinces him his apartment is actually her apartment. She is the firm center, sweetly spinning Darin and the rest of the film around in circles of befuddlement while she decides what she wants and when.

This aura of self-autonomy made Sandra Dee one of my figures of aspiration as a girl. In her characters, she lets the audience see the process of doubt and vulnerability while also making the decision. Her way of speaking is memorable: sometimes halting with clipped sentences and sometimes too many words spoken too quickly, but she really does always keep speaking.

Her openness onscreen is definitely why young me always preferred to rewatch her comedies rather than her melodramas--the vulnerability was too real. I have a very vivid memory of watching A Summer Place (1959, dir. Delmer Daves) as a 12-year-old hoping it would be another Gidget and my dawning horror as the melodrama played out. Sandra Dee played yearning angst and vulnerability so acutely--it hurt me. I must confess I have never rewatched the film, and to this day, hearing that wistful theme tune is enough to re-traumatize me.

Sandra Dee played Lana Turner’s daughter twice, most famously in peak melodrama Imitation of Life (1959, dir. Douglas Sirk), and again in the seedy Portrait in Black (1960, dir. Michael Gordon). Dee and Turner match up perfectly, both so adept at playing girls and women grasping for self-autonomy and self-preservation in a world that has no intention of making it easy. I wonder if Sandra Dee’s career had continued past her 20s if she would have found herself in Lana Turner-like roles?

Instead her final film appearance came in 1970, at the age of 28, in The Dunwich Horror (dir. Daniel Haller). She plays opposite another former teen-actor-with-substance Dean Stockwell in a freaky tale of the occult and monsters that feels subtly template-like for many films that followed. Her soft vulnerability amidst the chaotic production stuns. In Sandra Dee’s hands, Nancy is not a stupid, gullible woman led easily into danger, but an open and empathetic woman trying to balance danger against desire: a navigation that is true in every day life even when your job and studies do not include the possibility of your body becoming a gateway vessel for demons.

Oh Sandra Dee, I wanted to compose an ode to you, but I do not have all the words I need.

Oh Sandra Dee, you’re not a pastiche of people’s false memories, a relic from a plastic era, or the line from a song-- instead, resolve and humor, humanity and kindness, and an absolute knowledge of the ridiculousness of life--it all showed up on screen and bolstered a girl who desperately needed to see another girl triumph. 💖

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 09/05/2021.

-Meg

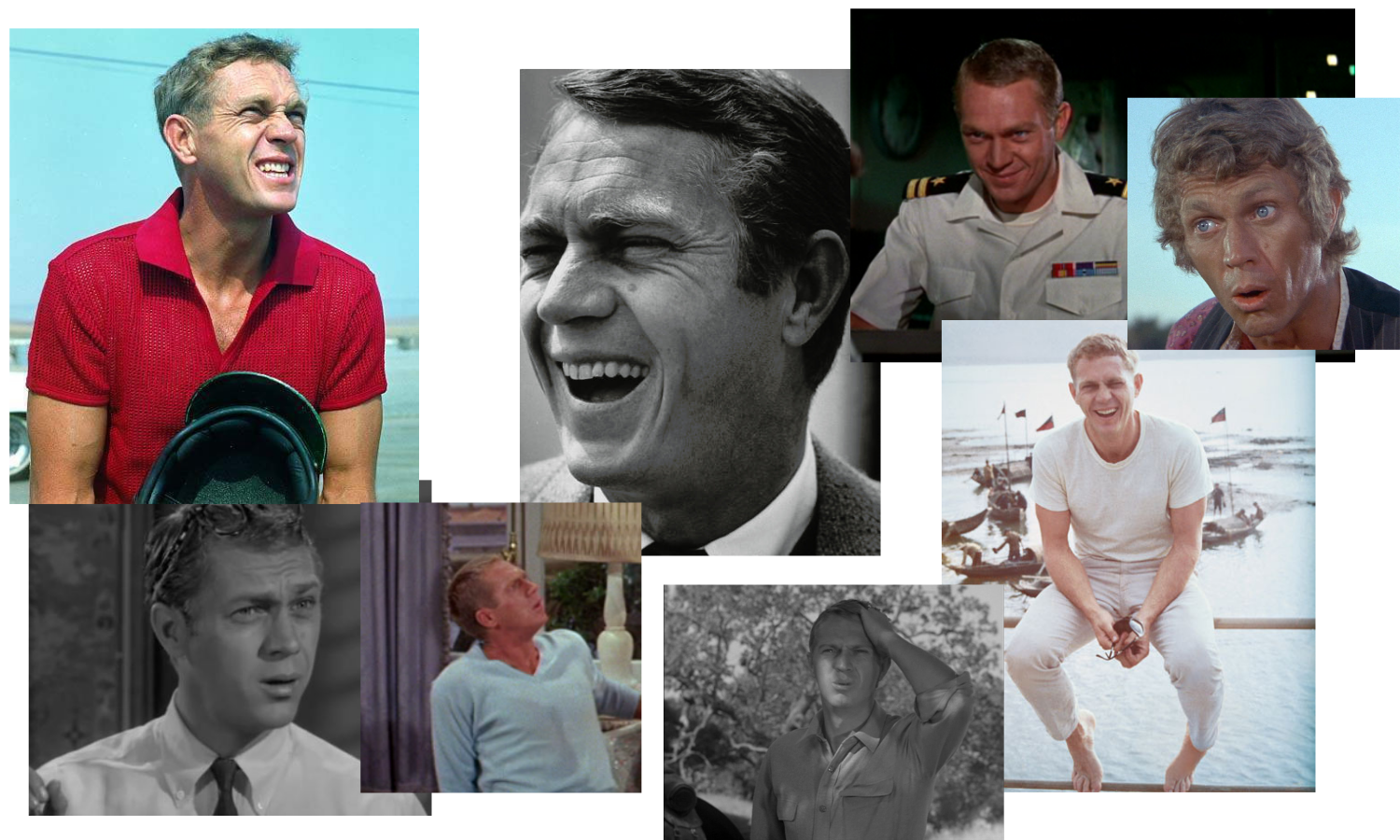

Steve McQueen, Cinema Goofball

Popular culture remembers Steve McQueen as the King of Cool, a paragon of stoic masculinity, a laconic man of few words and fewer emotions. But, what of the other side of Steve McQueen’s on-screen persona?

Popular culture remembers Steve McQueen as the King of Cool, a paragon of stoic masculinity, a laconic man of few words and fewer emotions. The remembered idea of him is two-dimensional, and–as a marketing scheme–highly successful: his name appears regularly in the lists of the most profitable dead celebrities. He is an image: stern, unflinching, immovable, untouchable. He doesn’t crack under any pressure, just like a Tag Heuer watch. He is “The Absolute Man” according to the vodka brand.

But, what of the other side of Steve McQueen’s on-screen persona? Not the vroom-vroom car chases and cool sunglasses and dialogue-free scripts. Not the decades of co-optive advertising. The other side: the much-maligned (but much-beloved-by-me), entirely uncontained, earnestly unsure total goofball.

I came to Steve McQueen early in life. He is my oldest brother’s favorite. Five years older than me, this brother always had a Steve McQueen movie playing, or a DVD lying about. My understanding of McQueen was formed first by the television series Wanted: Dead or Alive. And yes, he does play a cool loner bounty hunter traveling through the American settler west of the 1870s. But, his Josh Randall is also deeply connected to the people he meets along his travels, always getting involved, solving troubles, and occasionally forced into absolutely wacky shenanigans.

Burned into my memory, is an episode from the final season released in 1961, titled “Baa-Baa.” Josh Randall is sent in search of a lost pet sheep, there’s a singing chorus, montages of him chasing sheep over hills, and pratfall face grimace combinations not seen since the days of Cary Grant flying through Arsenic and Old Lace. That is my enduring image of Steve McQueen: flailing and just a little earnest.

I have written bits and pieces before about Steve McQueen’s depiction of masculinity. It fascinates me. It never seems to me to be the confident, unbreakable idea that endures from his most famous roles, but in actuality rather fractured and unsure, as if he was precariously holding himself together. Often the only outlet of emotions in these performances is violence. Once stardom took hold, there was an increasing unwillingness on-screen to divert from tightly-contained emotions and limited dialogue; almost as if to open himself up at all would be the end of his control.

This is a marked difference from some of the other enduring cool guys of the era, like Sidney Poitier, Toshiro Mifune, or James Garner. Their self-confidence felt entirely real and fully true to themselves in every kind of film or performance. James Garner was good pals with Steve McQueen, but also had this to say in The Garner Files, “He was a movie star, a poser who cultivated the image of a macho man. Steve wasn’t a bad guy; I think he was just insecure. … Deep down, he was just a wild kid. I think he thought of me as an older brother, and I guess I thought of him as a younger brother. A delinquent younger brother.” (Note: This is also what happens when you put two Aries together, I say as an Aries.)

That delinquent younger brother energy is a dominant theme in all of Steve McQueen’s “b-side” films: those films that do not comfortably fit into his steely iconography, and are left out of all the advertising and the cool montages.

Steve McQueen’s best performance comes in one of these films, Love with the Proper Stranger (1963). A romantic drama permeated with sweetness, it is McQueen’s softest role. His co-star Natalie Wood is glorious, confident, and self-assured even while her character is facing extraordinary fears and pressures. McQueen plays his character hesitant and awkward. He is a cool-cat jazz musician who trips over and mumbles his words and hunches and slouches his body. The finale of the film is the ultimate goofball gesture–and stunningly earnest.

Sometimes, Steve McQueen’s ventures into goofball territory are far less earnest. The Reivers (1969) is a film I would charitably describe as YIKES (but what a supporting cast! Rupert Crosse! The great Juano Hernández!). It is also a strange amalgamation of his competing film energies. There is the obsession with a car and emotions processed via violence (particularly directed at women), but there is also slapstick slipping in the mud and very big reaction faces. There is an internal battle for his performance soul warring throughout this film, and violent goofball is not really a comfortable spot to land.

Critical and public appraisal of McQueen’s ventures outside his narrow sphere has never been laudatory. Anything he did that came close to comedy has been thrown out in confusion with a note that it is “really not his thing.” Yet the problem with The Reivers is not the earnest comedy, but the elements of coldness and violence. Steve McQueen’s image sells luxurious watches under the promise that he doesn’t crack under pressure. Ice cold silence sells. Flailing limbs and high-pitched scrambling does not sell vodka--apparently!

Yes, the time has finally come to talk about The Honeymoon Machine (1961). This movie is bonkers, but with that impeccable internal logic that makes 1960s comedies run so smoothly in their own wild realities. It is also peak goofball McQueen. As a scheming sailor with a plan to game the roulette wheel in a Venice casino using a naval computer, he talks extraordinarily fast–often at a high-pitched squeak–and says more words than most of his other films all put together. He stumbles and trips and sways. He is a delight. He hated it.

He walked out of the first preview, and said he would never work with MGM again.

I think it is one of the most endearing McQueen performances. To watch him play a James Garner comedy role without James Garner levels of self-assurance is such a feat of sincere effort. He pulls it off too, because it is all McQueen. He may be playing a zany goofball, but the threat of violence feels ever-possible as he hops about manipulating everyone around him and talking about Nietzsche.

I love Steve McQueen’s on-screen work. 12-year-old me somewhat unconsciously attempted to model my stride on his after watching that long opening shot of him walking down the street in The Cincinnati Kid. His Vin in The Magnificent Seven is one of my favorite characters dear to my heart. His work as Sweater Detective in Bullitt is an aesthetic triumph. Wanted Dead or Alive fills my soul with joy (and I once wrote a piece about its fashion when I was 17). That episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents where he bet Peter Lorre his finger is a lesson in building tension in 25 minutes (I also love that episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents where he is a goofball Martian).

But, my understanding of Steve McQueen is not an image used to sell watches and vodka and cars. My Steve McQueen does sometimes crack under pressure. Sometimes, Steve McQueen was bold, violent, cold, angry, and harsh–causing pain that ripples. Sometimes, Steve McQueen was fractured, unsure, flailing, earnest–looking for a safe route to just be. Sincerity even in its tiniest measure is a hard-won human triumph! Long live the sincere goofball cinema of Steve McQueen! (Maybe don’t watch Soldier in the Rain though.)

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 01/10/2022.

-Meg

“I am not loveable”: Laurence Harvey and the performance of self-presentation

“Someone once asked me, ‘Why is it so many people hate you?’ and I said, ‘Do they? How super!’ I'm really quite pleased about it.”

“Someone once asked me, ‘Why is it so many people hate you?’ and I said, ‘Do they? How super! I’m really quite pleased about it.’”

Laurence Harvey fascinates me as an actor. As someone who had a relatively low-impact career (and certainly a short life, dying age 45), his acting continues to inspire a remarkable level of divisive responses among film people™. I have never quite been able to figure out exactly why, but it does seem rather instinctual. And, I am not usually one to wade into film people™ fights without a firm ground. (You can find teenage me timidly acknowledging, “people either love him or hate him,” in a review of The Ceremony.)

Nevertheless, my first instinctual response to Laurence Harvey was absolute delight. I was maybe 11 or 12, and I saw his episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. It has stayed firmly planted in my memory from the pure audaciousness. It is quite gruesome and unrepentant. Harvey plays the titular chicken farmer named Arthur, a charming but basically anti-social figure. He opens by telling the audience, smiling, “I am a murderer,” and then narrates his story. He murders his fiancé, disposes of her body in the chicken feed, raises chickens on that feed, and eventually sends some gift chickens to an investigating cop. The cop is so enamored with the taste, he asks for a list of feed ingredients. Arthur obliges, turning to the camera to state smoothly, “All but one. I left out that one special ingredient that really made it.” There is no justice and there are no consequences. (Hitchcock does offer a cheeky closing statement about the chickens growing to an enormous size and then probably killing and eating Arthur.)

I was transfixed. His character, and the story, were certainly misogynistic (a common characteristic across many Harvey roles), but there was something that intrigued me: the utterly manufactured façade of a self-image he projected.

Around the same time, I unintentionally saw his episode of Columbo (released in 1973, just a few months before his death): he played an emotionless chess freak murderer. In this, his character is once again set apart from natural and expected human warmth and emotion. I said, “Well, well, well. Tell me more.” (Let us not delve into my childhood psyche nurtured on too much Hitchcock and Columbo, and the Beatrix Potter story in which Tom Kitten is almost turned into a roly-poly pudding by giant rats.)

From then on, I kept an eye out for Laurence Harvey (carefully learning, with a couple missteps, to differentiate his name in a cast list from that of the viscerally terrifying and despicable presence of Lawrence Tierney). What he had onscreen, I could never quite articulate in my blogging youth, but I understood it and was drawn to it.

His screen persona was always openly enigmatic. He never tried to hide the fact that he was hiding—hiding his true self; his true feelings.

I have always connected his depiction of masculinity with that of Steve McQueen actually. McQueen is held up in popular memory as some icon of masculinity in the same limiting and distorted fashion that Marilyn Monroe is held up as an icon of femininity. Of course, they were actually both much more—and infinitely more complex—than the shallow containment allows (more on the glorious Monroe another time).

McQueen’s depiction of masculinity is far more complicated (and interesting) than his popular legacy would suggest, and far more aligned with Harvey than immediately obvious. Just as Harvey’s characters were often steeped in misogyny, McQueen’s were often violent—uncomfortably so. But also fractured. As if the confidence to live and express himself only worked in a narrow, tightly-controlled sphere, and he better not say too much or change his ways too much—or everything might disintegrate.

McQueen’s characters distracted us from their internalized self-doubt with an erected façade of coolness. He looked cool, and did performatively cool things, and never said too much—so how could we say he was anything but supremely confident himself? The cracks showed through though. (And his own pal James Garner called him an “insecure poseur” in real life, which is blatant Aries v. Aries violence but I’ll allow it.)

Why have I taken a detour through McQueen to talk about Harvey? I think they both spent their short careers depicting unsafe men: men who correspondingly never felt safe themselves to just be. McQueen covered his characters’ fractures with uncannily good film choices and an ability to project coolness. Harvey never even tried to play his characters as anything but self-loathing.

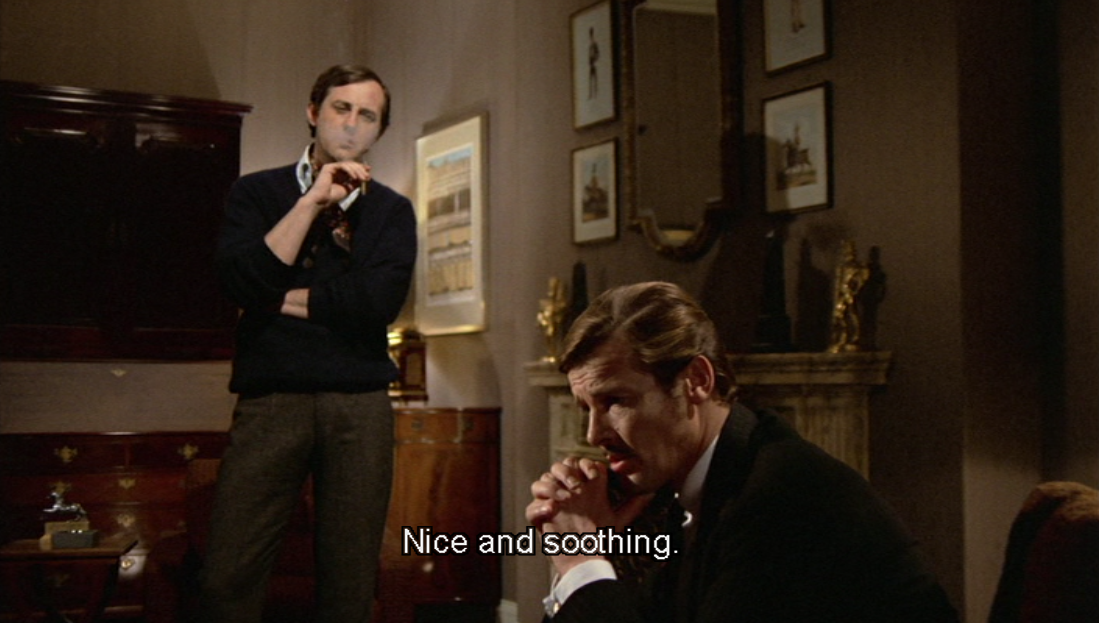

in his directorial debut The Ceremony (1963)

Laurence Harvey played roles of disliked men; broken men; loathsome men. To them, he gave the brutal honesty of self-doubt and self-loathing, often coupled with the inability to articulate these feelings—or even to fully understand the feelings for themselves.

His most famously remembered role today is probably Raymond Shaw in The Manchurian Candidate, but it is both typical and atypical Harvey. Typical, in the sense that his character is pretty universally disliked by all the other characters for much of the film, and also his emotions are tightly controlled, cold, and hardened. But, atypically, Raymond Shaw can articulate what he feels and understands about himself. He just has to get a little drunk first to say, “I’m not lovable. Some people are lovable, and some people are not loveable. I am not lovable.”

In his characters, he captured the angsty longing of James Dean, but without the openness; without the bare emotions; without the yearning reach toward other humans. As a teen Dean devotee, my innate alignment with Harvey’s work makes perfect sense to me. It appeals to the unconfident child with plans to show themselves to the world within a carefully chosen and constructed presentation.

It is a tricky business transposing screen persona over a fully-formed human person—and I really try to steer away from that in the general sense (*everyone ever trapped in a text thread while I discuss my favorite performers is now laughing heartily at this statement*). I do not know enough about the short life of Laurence Harvey to exhaustibly essay on it, but all due consideration to the death of the author, I can tell you why his screen persona—which often slotted in with his projected public persona—compels despite its carefully structured coldness.

His Joe Lampton in Room At the Top is fully concerned with the work of self-presentation. How can he react to the trauma and pain of life in a way that gives him strict control and power over his image to others? Of course, in this film, his image control is primarily routed through destructive and deeply misogynistic interactions with women. The self-loathing is strong here, and so is the childhood trauma. (He even steals a beat from James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause writhing-in-turmoil-with-a-toy-in-the-street performance near the end of the film.) The story concerns itself with the catastrophic ills of classism, and wealth’s casual habit of ignoring, dismissing, and then crushing to dust any would-be rebels in the system. Truly, an evergreen subject.

I recently rewatched this for the first time since my own angsty teens, and I was struck pretty much the same: adoration for the resolute clarity Simone Signoret gives her Alice, and a resigned *yikes* floating in the general direction of Harvey’s messy, messy Joe.

Joe is truly so very unlikeable in his attempts to beat his oppressors by becoming them. Harvey’s performance here works as a sort of thesis for his entire career of characters: resolutely individualistic, powered by self-loathing, somewhat irredeemable, yet still lit with a spark of uncanny energy. In every film, he was never anything less than calmly chaotic.

(his characters can oscillate between chaotic neutral and chaotic evil—but rarely even begin to whisper at a hint of chaotic good)

This is true even if you watch his early cinema work in England when he was more than once cast as some sort of charming rapscallion, life-of-the-party (perhaps more in line with his public self: a jet-setting, stylish Elizabeth Taylor BFF who managed to clash with seemingly every single introverted/subdued/serious actor he ever worked opposite). It is wild to see him play characters like the scamming talent agent in 1959’s Expresso Bongo (a fever dream of a film co-starring my very lively personal fav Sylvia Syms): a character who is likely intended to be seen as a troublemaker, but a fun one—yet in Harvey’s hands comes across as a somewhat unhinged menace.

This character type is a menace! It’s the archetype selfish conman who is always making plans to make money and treats the woman who loves him like trash while he’s bouncing off to another probably illegal scheme. Cinema is rife with them. Often, they’re a lot of fun to watch. Other actors use their own reserves of personal charm to smooth the rough edges; to make these loathsome men appealing. Instead, Laurence Harvey barrels full-throttle into forcing a response like, “god, there is no way I could spend more than two minutes with this person without screaming aimlessly in rage and frustration.”

In Darling, he’s enigmatic and absolutely without empathy. Both he and Dirk Bogarde play the male foils to Julie Christie’s incorrigible Diana Scott, but Harvey’s openly shallow work contrasts with Dirk Bogarde’s deeply shaded performance. Harvey offers no depth of emotion or feeling. It is obvious that his character is merely a shadowy projection. He makes no effort to humanize. He has built a blank façade. Harvey plays him as a compelling snake with no plans to warm up. Christie and Bogarde play people who cause varying degrees of harm through selfish pursuits, but the hook is that they do want to be happy, to be fulfilled, to be loved. Harvey’s Miles Brand shows no such desire—only a twisted, lightly-smiling desire to have control and power.

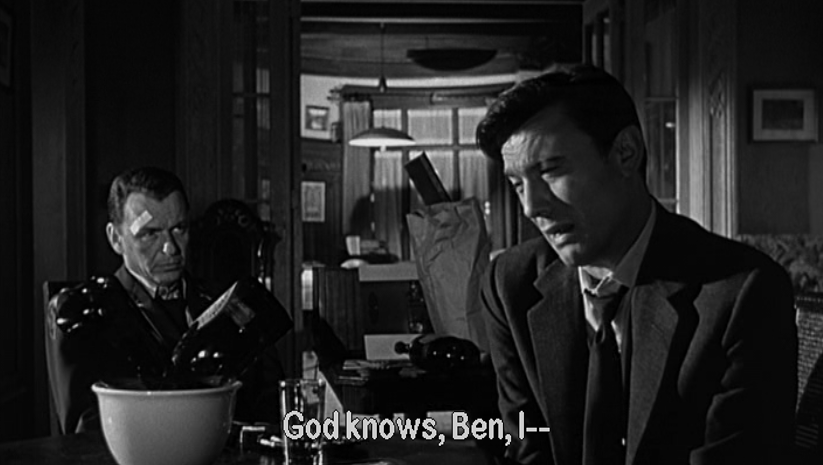

What is self-presentation if not an external action of innermost power and control? To dissect our own self-presentations is to ask questions: How do we see ourselves? How do we want to be seen? Every performer deals extensively in self-presentation. It is quite literally in the job description (I have now written “self-presentation” so many times it has lost all meaning and I am unsure how to pronounce it out loud anymore). But, few performers have ever made as much a concerted effort in pointing out the façade as Laurence Harvey did in his work. Is it damning him with undeserved praise to say that your loathing is what he expected? Yeah, his performances of being human register as somewhat cold, bleak, and out-of-step with any semblance of communal feeling. god knows, the cruel and cold male anti-hero concept is so dull and predictable (and always has been). I am not here to gas up that.

I am interested in the idea of that façade—the tightly controlled self-presentation—as a concealing act of self-protection.

“I’m a flamboyant character, an extrovert who doesn’t want to reveal his feelings.”

What happens when a flamboyant character (just look at his signature hairstyle—out there looking like a dandy from an earlier century), an extrovert who doesn’t want to reveal his true feelings, directs his first film?

You get The Ceremony (1963), a deeply idiosyncratic, stylized film that reveals many, many feelings. It is structured madness; structured chaos. The staging and shots are both uncluttered and extreme: purposefully drawing attention to themselves. Emotions are kept close inside with delicate facial expressions—and then exploded with full-body, uncontrolled movement.

I may be outing myself as a pretentious weirdo, but this is truly a favorite moment in cinema for me. There is a discomfort that comes from watching people let their bodies feel in outrageous waves.

This is a scene between Harvey, who has just escaped prison, his girlfriend Sarah Miles and younger brother Robert Walker Jr.

There is a line near the end of this clip that hits at one of Harvey’s themes in the film. He is specifically referring to the brutality of prison on a person’s spirit (side-note: abolition now!), when he talks of being reduced to the shadow a man.

“In there, I had time to think. I had never really taken the time to think before. What was I trying to prove? Where did it go wrong? And then I realized that it was too late. I was going to die knowing that I hadn’t lived. Do you understand what I’m trying to tell you? They try and reduce you into a shadow of a man. Your body begins to feel as if it doesn’t belong to you. Eating and eliminating. Detached. Your arms and legs begin to feel as if, as if they’ve been sewn on. Don’t think. Don’t feel. Flesh. Nothing. And you begin to believe it.”

While specifically a reference to the prison experience, it is also representative of some of the overarching themes (it can get a bit opaque and metaphorical in this film: just the way I like my pretentious cinema yum yum delicious) of power and control: who has control? how is power used? what makes a person human? how is each person’s humanity to be protected or destroyed?

To feel, as a person, like nothing more than a shadow—nothing more than flesh—is a grievous pain. Loss of autonomy is a grievous pain.

How do we see ourselves? How do we want to be seen? … How do we protect ourselves? How do we construct an image that cannot be breached? If we project coldness and inhumanity, do we save ourselves like the weakest prey puffing up before a predator? If we are sure we’re unlovable, can we say that being loveable is not the point?

Laurence Harvey’s canon of performances is filled with characters certain of their unlovability, and just as quick to present as unlovable in turn. Quick to project a self-image that prizes control and individual autonomy over relationship and community.

I think feeling loveable or not loveable is a universal human concern. It certainly looms quite dominantly when we’re young figuring out how to be. It has always explained to me why Laurence Harvey’s work compelled me. It said, "Build up your barriers! You’ll never be broken! (also you’ll never be happy!)”

Fortunately, I was also compelled in my formative years by two other male figures on my TV (look, I was homeschooled in the woods—I didn’t really see other adults except from my media): John Cassavetes and Mr. Rogers (honest to god, someday look for my comparison post about these two that’s been sitting as a draft since December).

Cassavetes: “And I don’t think a person can live without philosophy. That is, where can you love? What’s the important place where you can put that thing—’cause you can’t put it everywhere, you’d walk around, you gotta be a minister or a priest saying, ‘Yes, my son,’ or ‘Yes, my daughter, bless you.’ But people don’t live that way. They live with anger and hostility and problems and lack of money—with tremendous disappointments in their life. So what they need is a philosophy, what I think everybody needs, in a way, is to say, Where and how can I love, can I be in love so that I can live—so that I can live with some degree of peace? You know?

And I guess every picture we’ve ever done has been, in a way, to try and find some kind of philosophy for the characters in the film. And so that’s why I have a need for the characters to really analyze love, discuss it, kill it, destroy it, hurt each other, do all that stuff—in that war, in that word-polemic and picture-polemic of what life is.

And the rest of the stuff doesn’t really interest me. It may interest other people, but I have a one-track mind. That’s all I’m interested in, is love. And the lack of it. When it stops. And the pain that’s caused by loss or things taken away from us that we really need.”

Mr. Rogers: "Love is at the root of everything, all learning, all relationships, love or the lack of it."

I did not start writing this post intending to end up with Mr. Rogers at the finish, but I cannot say I am too surprised either. I did start writing this wanting to articulate why Laurence Harvey’s work meant something to me at my most impressionable ages. Truly what does a performer dead more than twenty years before I was born have to say through their film roles to a youth in the mid- to late-2000s if not, “Here is one way to live. You’re not gonna like it. But you’re gonna understand it anyway. Deeply understand it.” An extrovert who doesn't want to reveal their feelings? COULDN’T RELATE. I’M UNKNOWABLE! I’M UNKNOWABLE! (I scream into the void while absolutely oversharing, hence this very post on my own blog).

It is hard being human. It is hard to be human with other humans. It is hard to know yourself. It is hard to express yourself. What Laurence Harvey did with his work was to show the excruciating effort it takes to master an “unbreakable” self-presentation, and the open wound of making yourself invulnerable. The call of the void whispers that invulnerability is power, but the truth is in relationship and community with each other. <3

Please clap for the tremendous amount of self-restraint it took to not embed this clip of Daniel Tiger singing about being a mistake at the end of my post and thereby completing the parody of myself that is all this. Disgusting!

Also, this post is dedicated to Emmy—whose recent discovery of Laurence Harvey set me off on this journey down the old memory lane.

And, also to Kate—whose dedicated refusal to appreciate Laurence Harvey inspired many teenage Blogger/Twitter/Tumblr feuds on Friday nights.

-Meg

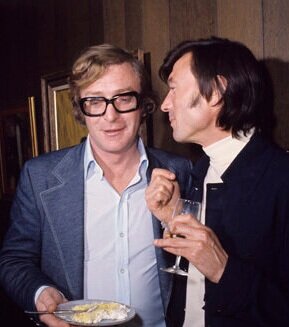

The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970)

The Man Who Haunted Himself // dir. Basil Dearden // United Kingdom

The Man Who Haunted Himself // dir. Basil Dearden // United Kingdom

Do you ever just know you’ll love a movie so much that you cannot even bring yourself to watch it? Not because you’re worried about being disappointed, but because you’re worried that you’ll truly love it too much. You’re worried that you’ll just feel too much?

Well, yes, I must say that is exactly how I felt about The Man Who Haunted Himself. I truly cannot remember where I first read about it, but it was in a book about movies and it was given a page with a single image. I was probably 12 or 13. I remember the entry was oddly dismissive. It vaguely explained that it was a rare and singular serious performance from Roger Moore, but it was not financially successful and was perhaps best forgotten.

Of course, that merely fueled my need to see the movie.

Roger Moore’s Simon Templar and I go way back. We’re pals. (The first car I ever drove—a vehicle that truly ran on pure force of will and literally a taped-together exhaust pipe—was affectionately named Simon.) I needed to see this film.

It was impossible to find.

It stayed a low hum on an ever-growing idiosyncratic list of films I NEED to see for one reason or another.

And then, eventually, Kino Lorber put out a release, and I gobbled up a copy last year.

But, I just couldn’t bring myself to watch it. I had waited too long. I instinctively knew I would love it, and what if I just loved it too much? Living alone a year into a pandemic lockdown is enough to make anyone worry that a pitch-perfect Roger Moore performance in a 50-year-old film is enough to break apart the loosely patched seal enclosing my deepest human feelings. Right?

Anyway, my old pal and partner-in-1960s-ITV-shenanigans Emm suggested watching it together this evening over video call and it was just the nudge I needed.

I almost cried before the film had even started, because I was thinking about how much I love cinema. WE’RE DOING GREAT OVER HERE.

Roger Moore plays Pel with such control and with such internalized emotion: be it self-loathing or exhaustion. His inhibitions reign. His façade of success hides an increasingly-apparent sense of isolation. As the film goes on, he becomes less sure of himself—and Moore plays that so acutely and so naturally, it’s astonishing.

So natural does he fit that when we see Moore play another version of Pelham—a charming, confident, self-assured, swaggering version with quick lines and quick smirks ala Simon Templar (or even Roger Moore’s own public persona)—it immediately reads as false; as diabolical.

This film pries open the unstoppable Roger Moore-like persona to focus on a vulnerable, unsteady character who lives only in others’ perceptions of him. He looks in mirrors wondering what they see.

This was Roger Moore’s personal favorite performance and film, yet it was not financially successful. He played vulnerable for the screen, and it was rejected. Lesson learned: he almost immediately went on to play James Bond for the next 100 years.

He was always dismissive of his own acting and talents. He claimed to have never received any critical praise for his own abilities. His success was based on the effectiveness of raising one eyebrow or the other. But, in the midst of the self-deprecation, he always had a word of earnest pride for his work in this film.

“It was a film I actually got to act in, rather than just being all white teeth and flippant and heroic.”

I suppose that is what (ahem) haunts me most about this film: it is a story driven by personal identity and the fear of being wholly oneself, yet the person who cared the most about the film spent the rest of his life feeling his work in it had never reached its audience.

Look, yes, I am going wild on my reading of this film, but that’s cinemaahh, baby. My ability to see earnest effort and vulnerability inside the most technically unexpected places is literally undefeated. (Also, everything written previous to this sentence was written late at night right after I watched the film, and the rest of this was written on a sunny afternoon two days later.) I can and will go on. But, first let’s talk about this scene that eerily and accurately describes how it feels to watch YouTube late at night when you cannot sleep.

^That’s just ASMR, baby!

(I have picked up saying “baby” in a really exaggerated way—primarily blaming aforementioned YouTube and particularly clips of James Acaster saying anything—and I am genuinely distressed to see it has migrated to my writing. But my writing style is conversational, so I am sorry to say I cannot delete the “baaabys” when they appear. It would be artistically unethical.)

Now that I have got my earnest emotional rush out of the way (and I cannot promise it won’t return at any moment), I really want to talk about the glorious aesthetics of this film. Because that is how you reach me: characters expressing inner turmoil+vulnerability with cool camera angles and maybe some fun neon lighting if we deserve it.

This film took it a step further. Basil said, yes, you deserve fun neon lighting! Lads, let’s give ‘em bisexual lighting while Roger Moore has an emotional breakdown driving a car in a rainstorm! We love to see it. :’)

The style of this is film is utterly and precisely and specifically a 1970 release—she’s delicious!

Each of the characters, not just Roger Moore’s Pel, are very interested in the way they visually present themselves to others. We see the art in the homes, we see the individual wardrobes and closets, we see the specific care put into hairstyles, and we even see the way characters pose and position themselves for effect.

Even the psychiatrist wears an intriguing pair of dark lenses indoors—contrasting with the slouchy look of his clothing.

The film concerns itself with unfulfillment, and while there is a somewhat plastic, shallow 1970 sheen cast upon it, there is also a uniqueness and a depth to each of the characters. Certainly, Pelham’s sense of self experiences fluctuations that Roger Moore plays with honestly a beautifully precise touch.

Hildegarde Neil plays Eve Pelham, Pel’s wife, with a level of malaise that hits perfectly. She is trapped in the same patterns and outcomes: all of which are unfulfilling. She does, however, present herself perfectly to the world and to her husband: it is one of the efforts she makes to break the patterns—to rise to the occasion. She is incredible.

Also, this gown is uhh v. dreamy.

Since I have taken a detour into clothing, let me now talk about Olga Georges-Picot. She also elevates the truly minor “random, mysterious woman required by script convenience to mostly lounge about in untied robes” character beats she is given. I was intrigued by her. I wanted to know more. She played the straight man to Pel’s shattering breaks in reality, but crucially, I always got the sense her Julie had a life that continued when she wasn’t onscreen dealing with that man haunting himself.

ALSO LOOK AT THIS ICONIC LOOK.

I—well—

okay, friend! love the way you present yourself to the world. love those paper flowers on the wall especially! fun!

Julie is the only person I felt like, “She’ll be fine.” And that’s truly an accomplishment as a secondary female character in a 1970 psychological horror production. I say without irony, GOOD FOR HER.

I need to end this post, because honestly soon it will devolve into me eventually just listing every lighting choice that I felt in my cinematic soul or something.

I really just want you watch it—and then leave me a comment, so we can start an email correspondence subject line: ROGER MOORE’S TORTURED FACIAL EXPRESSIONS.

When you get down to it, the reason I felt so deeply emotional about this (unfairly) forgotten film is because of the parasocial bond I developed toward Roger Moore when I was at my most impressionable age. I have actually never seen any of his Bond films (in the reverse of the opening premise of this post in that it’s a case of knowing I will hate a movie so much I don’t ever want to see it and feel too much), but as mentioned before—I adored his Simon Templar.

I grew up in an isolated circumstance, and did not have very much meaningful interaction with people outside of my family or the world outside a limited set of places. I felt constantly unsure of myself, and my place in the world. I was labeled a shy child, but I wasn’t. I was just a child without the safety to be fully myself—confident in myself—confident to know myself.

enter film and tv (mostly only films made during the Hays code [lol], and TV from the ‘50s/’60s).

Send the scientists to visit little Meg for some textbook parasocial relationships.

I had an entire pantheon of my people: the characters and actors and performers I sought to steal a little bit of something from—or maybe use as a Rosetta stone for my own already existing identity.

From Simon Templar, I saw confidence, an understanding of the absurdity of life, and the vague notion that one must be of service to others to live (to be sure, Templar’s level of service is highly dubious and highly errr self-serving). Simon Templar was fun and had a good time and always knew who he was in every circumstance or relationship. He was also taller than everyone else. None of these things transferred so easily or exactly.

This should say enough to see a glimmer of why Meg in her late ‘20s (just truly crossed that threshold two hours ago) would get so emotional about a film starring Roger Moore actively fighting his own persona of confidence to express an absolute confusion about himself.

mamma mia! I didn’t want to feel this much! </3

Anyone, please enjoy this below prescription that is also exactly what I’ll be doing when I get that second vaccine dose!

I also want to note that early into this screening, Emm suggested that Roger Moore would have been an iconic casting choice for Sir Percy in The Scarlet Pimpernel (a childhood favorite book for reasons which are probably odiously obvious), and I honestly will never forgive her for putting that idea out there knowing I can never have it. boooooo!

-Meg

Piranha (1978): “Terror, horror, death. Film at eleven.”

Piranha // dir. Joe Dante // United States

Piranha // dir. Joe Dante // United States

okay, I loved this movie. I am actually shocked how much I loved it. It was actually really…great?

Earlier, for reasons, I was rereading the obituary post I wrote for Bradford Dillman in 2018. I quite like this bit of writing actually. I feel like it articulates with sincerity and earnestness my appreciation in a way that feels personal to me. After reading it, I had to watch something with The Dill Man. Piranha had been circling around in my brain for a while, and it seemed like I was finally ready. I have spent the last few years watching (admittedly mild) horror films with Malakie and Paul, and I feel like I have become inoculated to the blood and guts and gore more than I ever was previously.

Piranha’s time had come.

(some mild spoilers may appear in this post, but nothing too wild)

This is actually my first Joe Dante movie. For some reason, in my mind, I had considered myself a fan of his work, and now I am realizing that probably just stems back to TCMFF 2014, and sitting in the audience while he introduced a 35mm screening of the original 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Martin Scorsese’s personal print). He talked and shared stories and it was fun time. I cannot remember a single story or anecdote he shared, but I do remember him talking about working with Kevin McCarthy—a very cool actor I have loved since I was kid.

In this film, Kevin McCarthy has possibly greatest screen entrance I have ever seen. This is literally his first shot in the film:

Literally always going for it. That’s one of the big reasons this film works so well, because it is filled with a collection of pros who know what needs to be done. I will talk a bit more about my beloved Bradford Dillman in a bit, but also here we have Heather Menzies—an actor I primarily associate in my brain not with The Sound of Music, but with this one incredibly off-putting character in an episode of Alias Smith and Jones. She is a lot of fun here as a “skiptracer” out to find two missing youths who have disappeared (got piranha’d in the opening scene). She is resourceful, and indomitable, and quite brave. She’s also the person Kevin is screaming at in his entrance, as she unfortunately is responsible for the piranhas getting loose in the waterways. ooops.

Also of note, Barbara Steele is glorious as an absolutely terrifying military-adjacent scientist. When she stares right at the camera and says the film’s final line, “There’s nothing left to fear,” I felt that chill running up my spine.

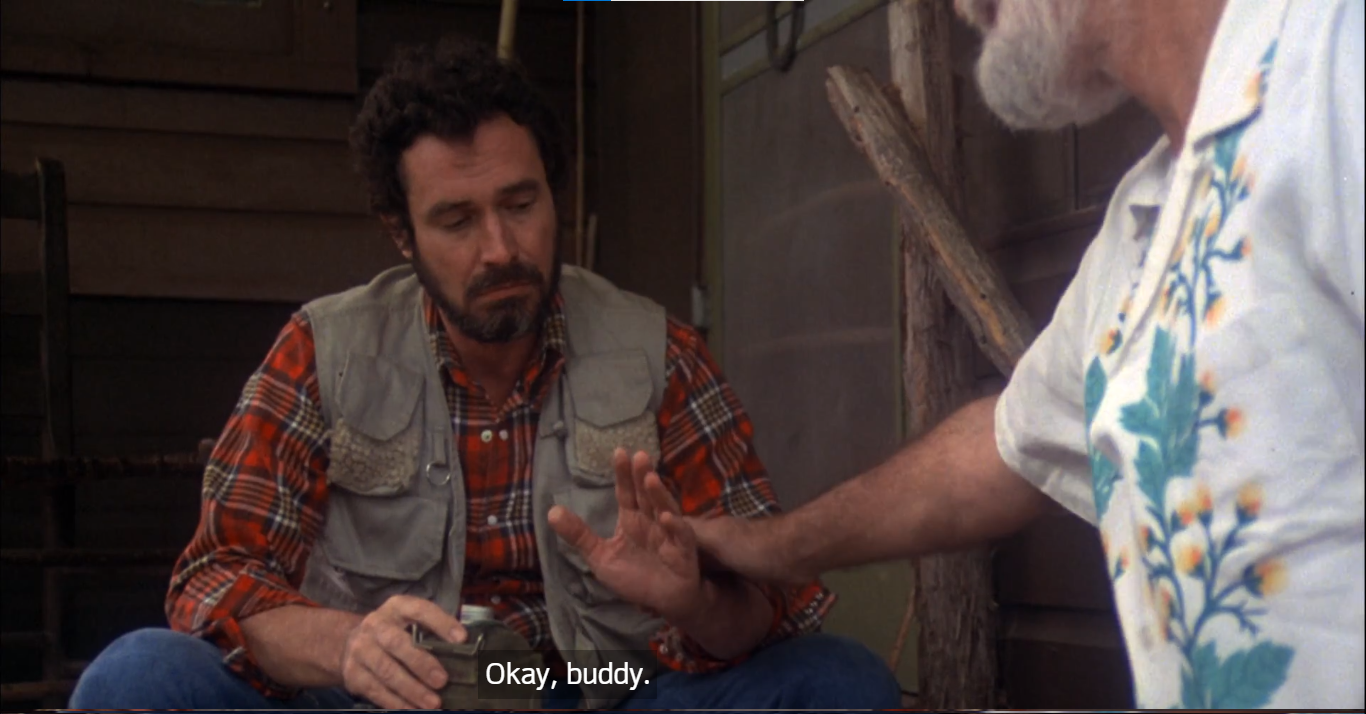

I also loved seeing a favorite Keenan Wynn popping up for a sadly short-lived role. What an evergreen performer he is in every film. I especially enjoyed the very sweet dynamic between him and Bradford Dillman. In those two, you have two actors used to creating something out of nothing—and, in this film, they are enjoying having a little something together. (also, I really like Keenan’s shirt in this scene. I would like to own it.)

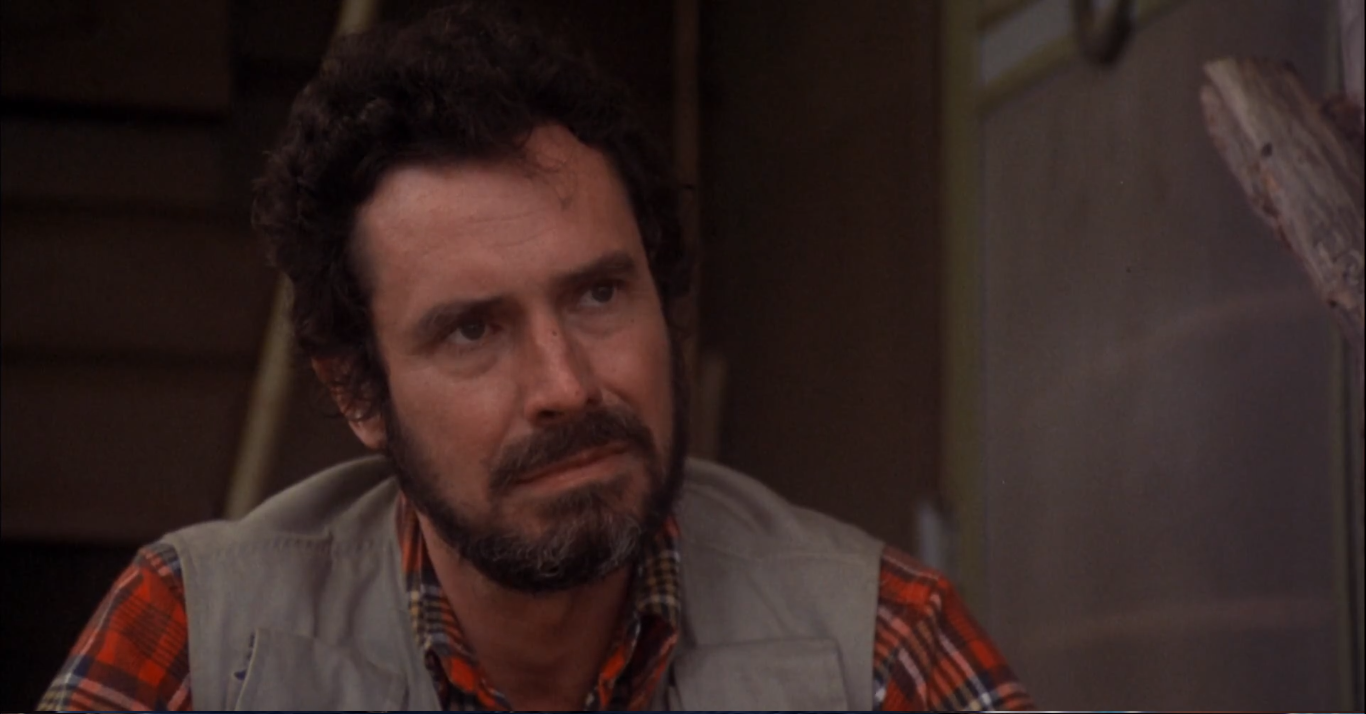

This, I suppose, brings us to Bradford Dillman. oh, how I love his work. And, oh, how perfectly he fits into this film’s somewhat straight-faced anarchy. This could have easily been very stolid in the hands of another 1970s B-actor. But, not in the hands of the owner of the best evil and/or bent smile in the business. What a charismatic joker.

He never offers half-measures, and every performance is interesting and fully-realized. He may have sometimes been given characters who were not interesting or fully-realized on script, but they never made it to the audience that way.

He could work his craft, but instead he often seems to want to twist his craft. A serious, trained ac-tor, he knows how to create achingly real human characters, but sometimes he seems to say, I can give you human reality, but why take that when I can give you realityish, you know, human+ ?

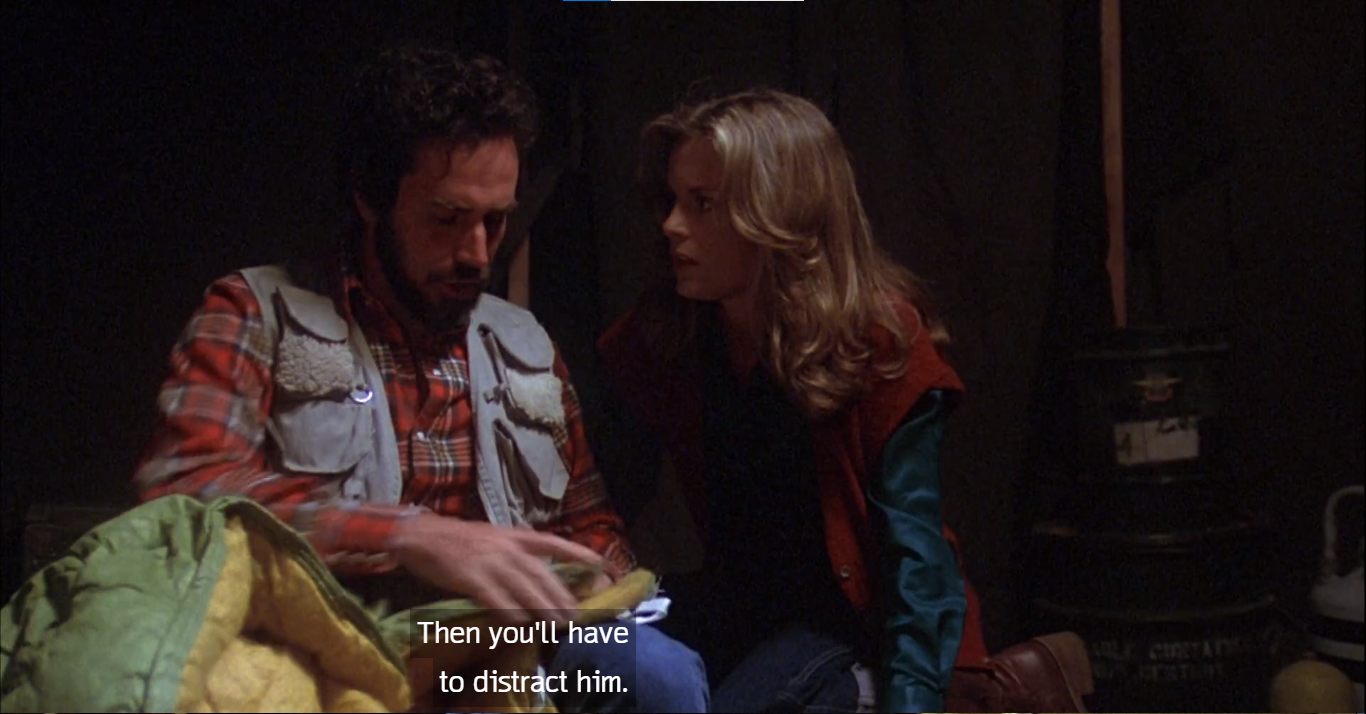

He reads this film so well. He brings both empathy and a transcendent twinkle to play inside the lines of Joe Dante’s often quite satirical work. There is the pre-piranhas quiet desperation, the frantic concern to make things right and protect his daughter, and the genuine grief and tears over the death of a friend. There is also the perfect understanding about just how ridiculous this all this. He and Heather Menzies have very good chemistry and fun rapport from the very beginning.

“Whitney: The piranhas...

Buck Gardner: What about the goddamn piranhas?

Whitney: They’re eating the guests, sir.”

The most unexpected delight in this movie for me was its absolutely unsubtle political messaging. I hits well for me, because I love a social-minded horror. One of the main targets of this film is the US military and the war+death complex. Turns out the ravenous, mutant killer fish were created by the US military to use against the Vietnamese. When the US were defeated and the war ended, the program was scrapped. The fish survived, because scientist Kevin McCarthy couldn’t bear to stop the good times and see his creations destroyed, and as Barbara Steele notes quite cheerfully, “There’s always going to be another war.”

Also targeted are the police (the domestic arm of the war+death complex), corrupt politics, corrupt business, consumerism, inhumane news practices, and adults who bully children. Each of these are responsible for the death and destruction. Each safeguard crumbles immediately in service of big money and big war…or just in service of belittling and bullying children. Some end righteously piranha’d, and others end the film with no consequences and no limits made on their power.

It is only individuals banding together in community to protect each other who do any good.

Also, speaking of individuals trying to do good, I have so many questions about the little walking piranha lizard that spends the entirety of the early lab scene skulking around unnoticed by anyone, but observing everyone and everything. I was convinced this would be ultimate saviour of the film, yet it is never noted by anyone or mentioned ever—nor is it ever seen again. WHAT DOES IT MEAN. THE PEOPLE WANT TO KNOW.

Me when you say, “Keanu Reeves seems like such a nice guy…”

“…but he’s a terrible actor. lol”

Another creature I would like to know a little bit more about is this little Godzilla fish in a tank who seems to respond to Heather Menzies’ disgust with an expression that can only be read accurately as, “Same to you lady!”

Incredibly, we almost never see any actual piranhas in this film. Instead, most attacks are first from a very funny, but also absolutely unnerving Jaws-like piranha view of the human victim and then just wild splashing, freaky trilling noises, and blood. lots o’ blood.

The true villains and obstacles in this film are less the mutant killer fish—and more the rich and powerful killer structural systems.

The need to escape military guard did necessitate this perfect exchange with some all-time Dillman line-readings, and some excellent reaction work from Menzies.

I think this film may have delighted me so thoroughly because I was just expecting some late ‘70s exploitation Jaws-knock-off with Bradford Dillman playing the Dr. Frankenstein. But, he didn’t create these monsters. He was just chilling! Trying to figure out his life on unemployment (after getting laid off), before it runs out and he needs to find a new job (who among us!). He has a convenient raft, because he built it with his daughter while they read Huck Finn! (raft in river bad idea tho as it turns out) As Emmy said when I insisted on live-messaging her throughout the film: “We love a Dadford Dillman!” Really, I can’t think of a better place to end this post than that borrowed line.

A fun movie, and I quite recommend it if you can handle a bit o’ gore that is mostly easy to glance away from as needed. I have only scraped the lightest bit of the surface of this film. So many other wild, and fun, and WILD things happen throughout!

I have to tell you, I wrote out the most wonderful and complete post. It was divinely inspired. I felt like everything was clicking along perfectly. Two hours later, I go to hit publish—AND THE COMPUTER GLITCHES AND EVERYTHING IS LOST DRAFT AND ALL. So, this is me just writing scraps at 3AM—typing with no small amount of rage. Once I write something out about a movie or talk it out with someone, it’s lost to my brain. I can’t get it back. Only vague notes of it. I couldn’t even begin to just retype it. So I just wrote little bits here and there of new, worse words. RIP Piranha post that read like poetry hope you’re in a better place. 💔

-Meg

cinema’s hottest coupleTM

plus bonus cinema’s second hottest couple™

Machine Gun McCain (1969), dir Giuliano Montaldo. A forgettable film with absolutely bonkers dubbing (why are you dubbing Gabriele Ferzetti, you cowards!) and no Falk-Cassavetes onscreen fun, but it does give us 8 beautiful minutes of pure charisma and presence when Gena Rowlands strolled onscreen. Love to be dazzled by cinema’s hottest couple™.

The Drowning Pool (1975), dir Stuart Rosenberg. A meandering film, and not in a good way: boring. (also extremely queasy exploitation of Melanie Griffith). The actual drowning pool sequence is delightful. But, I digress, ad I am really here to talk about cinema’s second hottest couple™. Joanne Woodward showing up to give us the caftan-wearing, lounging about goods.

-Meg

GIVE US THE MACHINE GUN LOVERS PREQUEL WE DESERVE! GIVE US ROWLANDS + CASSAVETES BONNIE & CLYDE!