Bikini Beach (1964) or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Embrace Joyful Nihilism

Bikini Beach // dir. William Asher // United States

We have had more than one successive day of sunshine here in Seattle, so yes, I am calling it: SUMMER IS HERE! As with many things in life (I resisted adding a heavily sighing “these days”), summer is more of a vibe than an actual tangible construct. So, to celebrate that, I want to celebrate a film that truly understands why vibes are more important than tangible constructs.

Bikini Beach (1964), dir. William Asher, is basically the third in a nebulously numbered series of Beach Party films (whatever the true number of films in the collection is--I’ve seen them all), and it is also the best film of the entire series.

(Quick vibe-check: if you think the best Beach Party film is Beach Blanket Bingo, respectfully, please either keep that to yourself, or quietly exit today’s lecture--thank you!)

Its status as best is perhaps based entirely on the initial determination of my 14-year-old self, but I truly do trust that 14-year-old me remains the best judge of 1960s teen surfer comedies, so we are running with it.

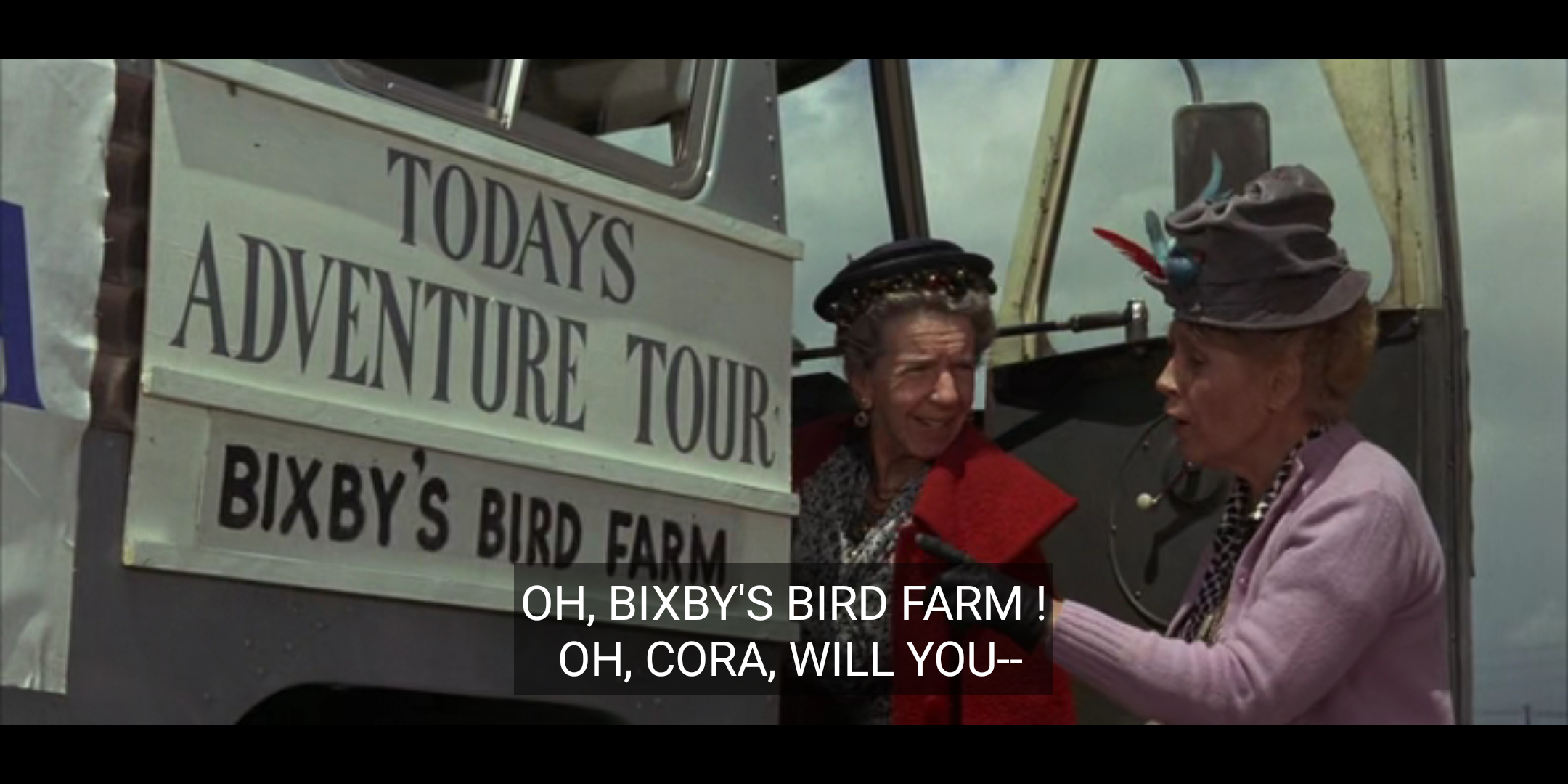

14-year-old me is also where our story begins today, as that was my age upon first viewing this cinema treasure. It was 2008, and back then, Hulu used to have an entire library of ~underappreciated~ 1960s movies to watch for free without subscribing (reach out to discuss Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine at length anytime). I saw this, and quickly showed my childhood best friend and it entered the sleepover rotation, and the rest is history, and I am definitely going to text her “Oooh Bixby’s Bird Farm!” as soon as I am done typing this up--and she will immediately get it.

There is something to the fact that all these films were made by American International Pictures (all hail cinema) very quickly and very cheaply and intended to be direct-to-the-teens movies, and somehow that strategy was still holding up and working out forty-five years later.

The formula works, because it is basically all bright colors, sight gags, and occasional footage of stunt surfers wearing visibly fake Annette wigs. More to the point, the formula works, because Annette Funicello + Frankie Avalon really are fun and charming onscreen. Their performances are truly enjoyable, and they have sweet, friendly chemistry together (I am not the first to say this, obviously, but consider it very Doris Day + Rock Hudson in the best ways).

In this film (and others in the series), Annette Funicello has the often thankless role of trying to get Frankie to think about his future, but she does so with a mischievous twinkle and a strong presence. She also really knows how to sing softly+sweetly while walking on a rear-projection beach at night-time, and I am not being ironic by saying that. It is an actual skill to inject so much personality and professionalism into formulaic, low-budget films. Plus, I have never stopped thinking about these pants.

And, Frankie Avalon in Bikini Beach? Well, let’s just look at the first note I scratched out while considering what I wanted to write here: “Tour de force Frankie Avalon the only good teen boy 60s actor.”

Those who know me well, will know that while I do enjoy frequently saying the phrase tour de force out loud, I do tend to truly reserve it as a description for work like Paul Robeson in Body & Soul, or Irene Dunne in The Awful Truth, or Tom Hardy in Venom. So, when I say Frankie Avalon’s dual role (!!!) as Frankie and as The Potato Bug is tour de force, I truly mean tour DE force. On that note, what I am about to tell you is going to make you reconsider trusting 14-year-old me as a cinematic arbitrator, but actually it should just reinforce the objectively career-pinnacle work Frankie Avalon does here.

So, Frankie plays two parts here. He plays “Frankie,” the lead youth who lives each day as it comes and regularly breaks the fourth wall to chat to the audience, and he also plays The Potato Bug, a British pop singer ala The Beatles as interpreted by Terry-Thomas (the accent and the gap tooth really give away that inspiration). At one point, “Frankie” dresses up like The Potato Bug to fool Annette, and shenanigans ensue. Anyway, yes, 14-year-old me--an already sophisticated film fan with a wide-range of film interests and deep well of films watched--did, in fact, think that there was a different actor playing The Potato Bug and that when “Frankie” pretends to be The Potato Bug in-film that it was just Frankie Avalon doing a convincing but not perfect impression of the actor playing The Potato Bug. AND YES, when the end credits scroll said,

Frankie Avalon as Frankie

Frankie Avalon as Potato Bug

I GASPED.

I still cannot explain this absolute lapse to you except that it was a tour de force performance.

Also, this bit of trivia was included in my Beach Party boxset: "Frankie Avalon's make-up and heavy accent were so convincing, visitors to the set were not aware that he was playing the role of Potato Bug." Think kindly of 14-year-old me. I was not alone in this.

Now that proper deference has been given to this iconic ringer performance, consider the other members of the cast. These movies have a structure that, along with the regular youth crew, includes an antagonist (usually older familiar actor), a sparring partner for the antagonist (usually older familiar actress), a guy running a hangout (usually a Don Rickles or Morey Amsterdam), and a surprise cameo guest from a true legend.

The reason Bikini Beach is the best of the series is that each necessary ingredient is there, but also actually good. In the original Beach Party, Robert Cummings plays the older familiar face role as a professor “studying” youth culture, and comes off as such a creep that even Dorothy Malone sparring with him cannot save the cringe. Here, however, we have Keenan Wynn--an actor who can slot in anywhere in any film and elevate the whole thing. He plays an unscrupulous land developer who is trying to turn public opinion against the surfers, so he can buy up land for his assisted living empire. He does this by bringing along his pet ape Clyde everywhere to prove that the youth are no better than apes. He offers gravitas and wit to a role that requires him to be chauffeured around by a person in an ape suit on rear-projection.

Here his sparring partner is Martha Hyer, a local school teacher who is hip and wants to advocate on behalf of the youth. She is great, and gracefully dances the Watusi with the aforementioned person in the ape suit. Don Rickles owns the local drag strip and the hangout and paints on canvases all over the bar. A strange older man, who is only visible from the back, keeps looking at the paintings but never buying. When his identity is revealed in the finale--it is a delightful surprise. I won’t spoil, but other films include cameos from Peter Lorre, Vincent Price, and Buster Keaton.

There is also the regular crew including Donna Loren (and her headbands!), Jody McCrea (exact replica of father Joel), Candy Johnson (fringeeeee), Stevie Wonder (still Little Stevie Wonder here), and--in typical inexplicable, but oddly obvious fashion--Timothy Carey playing a pool-playing, growling South Dakota Slim. Never let it be said that there was no edge to Annette + Frankie’s beach.

In fact, there is a bit of unsettled anarchy to these films. Certainly, there is a peculiar kind of lawlessness present. They never once address any big contemporary social issues, and they are almost uniformly white (and sometimes have casually racist elements like Buster Keaton playing a “native witch doctor” in How to Stuff a Wild Bikini), and they cannot be considered any sort of radical or counterculture art. However, they do offer pure, ungraded joyful nihilism.

There is a utopian element to Bikini Beach, with the unsupervised young adults living communally on the beach: sharing resources and experiences. They take each day as it comes, learn new things, and spend a lot of time dancing in the sand. The youth are mostly kind, or at least benign, and tend to solve individual problems by coming together. There are always hints that they know the world does not work that way, and so they just choose to ignore the world. In the ecosystem of the Beach Party, that works out for them just fine. They live outside of general society, and have created a new one.

In this society, plot, logic, and physics mean nothing. It is all vibes. 100 minutes of colorful vibes. There is no sight-gag too disruptive, and no innuendo too obvious, and no pratfall too chaotic to be included. There are chase scenes, a breaking up the bar fight, a little surfing, some drag-racing, and multiple musical numbers. Physics means nothing, but commitment to the film is everything. And, everyone involved was professionally committed to the silliness. Many years later, William Asher (director, co-writer, and essentially architect of the series) said about the “sheer nonsense” of the films, “The whole thing was a dream, of course. But it was a nice dream.”

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 05/05/2021.