The Year of Joan Hackett

I love Joan Hackett. She was a singular actor. I embarked on the Year of Joan Hackett in a bid to complete her filmography.

I love Joan Hackett. She was a singular actor. Onscreen, she had the best and the biggest energy. She was sweet and savory. She was inimitable. She had an instantly recognizable voice and the hair of a turn of the century Gibson Girl. She could make you cackle with laughter or break your heart into tiny splinters. She was explosive and tender. She was overwhelming and gentle. Like the best of our immortalized actors, watching her onscreen is like spending time with a dear old friend.

In January, I was watching her in The Last of Sheila (1973) for the first time (I know! I know! A film made entirely for me that I somehow had not seen age fifteen late on a Friday night with a library DVD). I was thinking about how much I adore her work, and how much I actually hadn’t seen of her short career.

I embarked on the Year of Joan Hackett in a bid to complete her filmography. This is something I successfully did in 2023 with Sandra Dee (and never got around to writing about, naturally), and attempted and failed in 2024 with Audrey Hepburn (so close; I will circle back around to the Lady Hepburn). I am using Letterboxd’s version of her filmography (via TMDb) as it limits her work to feature films and television movies: 31 titles versus the 69 credits on IMDb (this still leaves me so many delicious 1960s and 1970s TV episodes to enjoy at my leisure).

The dark winter months were very successful and I watched many new-to-me Hacketts. I have admittedly fallen off since the summer, but, as the days grow shorter, my appetite for spending time inside laying about on my couch increases.

I have decided to chronicle My Year of Joan Hackett here, and update until I am completed. I have been keeping a ranking of Joan Hackett, and I must say that is purely based on some indescribable Hackettness that I am personally determining and nothing else. Does the film give me the hit of Hackett that I crave? Does Joan get to say or do something wild or chaotic or emotively tender? Is she brittle or is she full of life? The Hackett variations are myriad.

Joan Hackett Filmography

Joan Hackett Ranked

Support Your Local Sheriff! (1969)

Joan Hackett as Prudy Perkins was foundational for me, and I still love to rewatch. I never grow tired of her weirdo performance. All awkward limbs and deep, abiding rage. When she yells, “Death to all tyrants!” and tries to chain herself to a support beam at the city council meeting and they all respond like she has done this many times—perfection! Her chemistry with James Garner is so unbearably generous and fun.

2. Five Desperate Women (1971)

I first watched this eight years ago, and I was obsessed. Truly the stuff the TV movie dreams are made of. A perfect cast from top to bottom, but Joan Hackett still stands out as she spends her entire run-time lying profusely to everyone around her while wearing all manner of elegant fashion before breaking down and admitting she has a TV in every room playing constantly so she won't be reminded she's ALONEEEEE. There is nothing better than Joan Hackett amidst a group of women. You can watch on YouTube here.

3. The Last of Sheila (1973)

As mentioned above, this was a 2025 new-to-me film, and it quickly jumped into the top echelon of Hackettness. She is so good and vulnerable and brittle but with a very sharp edge. She plays everything just right. SPOILER IN WHITE TEXT (HIGHLIGHT TO VIEW): Based on her performance, I genuinely thought that she was one who belonged to the “You are a Homosexual” card, and that she was having an affair with Raquel Welch. THE SIGNS WERE ALL THERE (IN MY HEAD LOL). END SPOILER.

4. The Young Country (1970)

Okay, so this isn’t very good (and was remarkably hard to find to watch), but I do love visiting the wacky mind of Roy Huggins. The unfortunate thing is that he was always trying to make Roger Davis happen as one of his charming rapscallions, and well the man was full of menace onscreen! (He played the only man that Kid Curry ever killed!) He is somehow the lead here instead of Pete Duel who plays a supporting role (this all got sorted out when Alias Smith and Jones premiered the next year). None of this touches Joan Hackett though with her signature hair poof and the driest, smirkiest delivery. Perfection. I have probably ranked it too high, but it’s just such potent synthesized Hackettness. Joan Hackett + Pete Duel is also the smoothest delight. They have wonderful chemistry and their scenes together are the best in the movie. (I have also cheated here and added a photo to the slideshow from her guest appearance on Alias Smith and Jones, because she is just a perfect third with boys).

5. Reflections of Murder (1974)

The girlfriends are plotting murder on an unnamed island off of Seattle, and we are having a great time! Joan Hackett was the queen of full-bodied vulnerability, and she ably portrays a journey into hysteria. I loved her chemistry with Tuesday Weld. And, here, she also demonstrates her skill with acting alongside children. She always has a true sweetness and gentleness in that regard. Watch on YouTube here.

6. Rebecca (1962)

A truly short (sub-hour) live television adaptation of Rebecca (notably adapting the 1940 film, and not the novel), but oh my, she is so good as the Second Mrs. de Winter. I would have loved her in a full adaptation. She has that exact right combination of nervousness and steeliness and freshness. This one is somewhat of a rarity and I had to rent on VHS from my local video store.

7. The Other Man (1970)

Isolated house on the rainy northern Pacific Coast! Melodrama! Joan Hackett doing her greatest hits! This is a really strong Hackett performance. The edgy vulnerability. The gentleness that can explode when provoked by cruelty. The fight between staying safe (internalizing emotions) and being authentic (emotions out loud). She is the star here, and works well with Roy Thinnes.

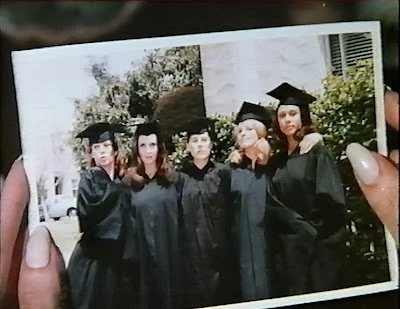

8. The Group (1966)

A wonderful cast of women makes up the group, and there is not an underwhelming performance in the bunch. However, obviously, I am Hackett-biased, and I think she brings a very lovely and very Hackett brittleness here. She stands out even among all the great actors around her. She also just looks so good in a 1930s haircut and dress.

9. Assignment to Kill (1968)

Joan Hackett so cute and charming in this! I love her flippy hair and slacks and ties. I love her eye rolling and quipping. Alas, however, she is not the lead of the film, so we do not get to spend every minute of screentime with her present. It would have been a better film if that was the case. When her character departs the film, so does all my interest. This is a really fun role to see her in, and I will pretend she left that boring man and safely continued her quipping in slacks and ties for the rest of her days.

10. How Awful About Alan (1970)

It would have been entirely easy for this film to have cast Julie Harris and Anthony Perkins as sensitive, awkward freak siblings and called it a day (I would have still watched that film) without bothering to cast anybody good in the role of the patient and supportive fiancé. Thankfully, they cast Joan Hackett. She's darling here, and does some of her inimitable work managing to imbue goodness with such shape and substance. (A true Pisces, I suppose.)

11. The Possessed (1977)

Don’t ask me any questions, but yes, I would love to go to Joan Hackett's School for Girls! This is the absolute pinnacle of Joan Hackett stressed-out acting—she reaches spontaneous combustion levels of work-based anxiety (whom among us cannot relate). This is a performance that really shows how she can hit every big and small beat so perfectly.

12. The Treasure of Matecumbe (1976)

A deeply questionable film that cannot be recommended. Joan Hackett does however have poofy hair, a wild accent, a job running scams, and a gentle aunt energy with the child leads.

13. Dead of Night (1977)

TERRIFYING. I am not equipped for this kind of imagery. Oh, she is so good here as a mother who is losing her mind with grief and maybe also whoops summoning demons? Many actors talk about how it can be hard to act opposite children, but Joan Hackett worked with children many times and always has such a perfect energy match to them.

14. Pleasure Cove (1979)

A nothing of a TV movie, but she is so delightful as one-half of a pair of battling exes who show up at the same resort. She is a professor leading along a young dummy of a boyfriend, and generally being her caustic best. She is simply too much fun and I love her big hair and track suit.

15. The Escape Artist (1982)

I find it singularly painful to watch films starring the O'Neal children. Vulnerable children with no advocate; no safe adult. This one has a distinct sadness as Griffin O'Neal's character spends the film trying to cope with the enigma of his father's death and the confusion and grief of that loss. However, Joan Hackett knows how to work with children, and she is really lovely here in one of the final roles. Her interactions with Griffin sing with such a gentleness and genuine sweetness.

16. The Long Summer of George Adams (1982)

A Joan Hackett + James Garner reunion! Their chemistry so exactly right thirteen years after Support Your Local Sheriff! This was one of Hackett's final performances, and her energy is the heartbeat to this story. (I do not forgive Garner’s character for his betrayal though!)

17. Paper Dolls (1982)

A Joan Hackett v. Joan Collins Joan-Off! A small supporting performance from Hackett, but she is fun as a demanding stage-mom of her teen model daughter. She is all business with a slicked back pony.

18. One Trick Pony (1980)

Joan Hackett is a minor character in this film, so she does not have much to do. She does get to appear wise and wry and also looks great as a sleek blonde. She is the smartest one in the movie and I would have loved to watch her movie.

19. The American Woman: Portraits of Courage (1976)

When I say Joan Hackett completism, I mean COMPLETISM. This is a fascinating artifact of 1976. She plays Belva Lockwood, lawyer/politician, for one scene recounting a story about defending a woman in court against her husband. Not a lot to say here, but I do think that Joan Hackett always looks incredible with poofy late 1800s hair and she does have such gravitas. A natural pick for the role.

20. Class of ‘63 (1973)

A TV movie with so many unfulfilled plot-lines, I wondered if the version I saw was edited? Anyway, my only feeling after watching it was: Joan Hackett, a queen! Leave both that short loser and that tall loser behind. Live your life!

21. Stonestreet: Who Killed the Centerfold Model? (1977)

One thing that simply was not utilized enough in Joan Hackett’s career was casting her as a villain. She really is fun here as a sinister lady with giant glasses doing evil business things from behind a phone. Watch on YouTube here.

22. Flicks (1983)

I believe this was her final released performance. Her parody vignette as a spaceship commander ala Star Trek is somewhat painfully unfunny, but not her. She is just a delight. Imagine the dream of her playing this role in a serious production.

Joan Hackett in Progress

Will Penny (1967)

Lights Out (1972)

Rivals (1972)

The Terminal Man (1974)

Mackintosh and T.J. (1975)

Mourning Becomes Electra (1978)

Mr. Mikes Mondo Video (1979)

The Long Days of Summer (1980)

Only When I Laugh (1981)

Playlist of Films Available on YouTube:

-Meg

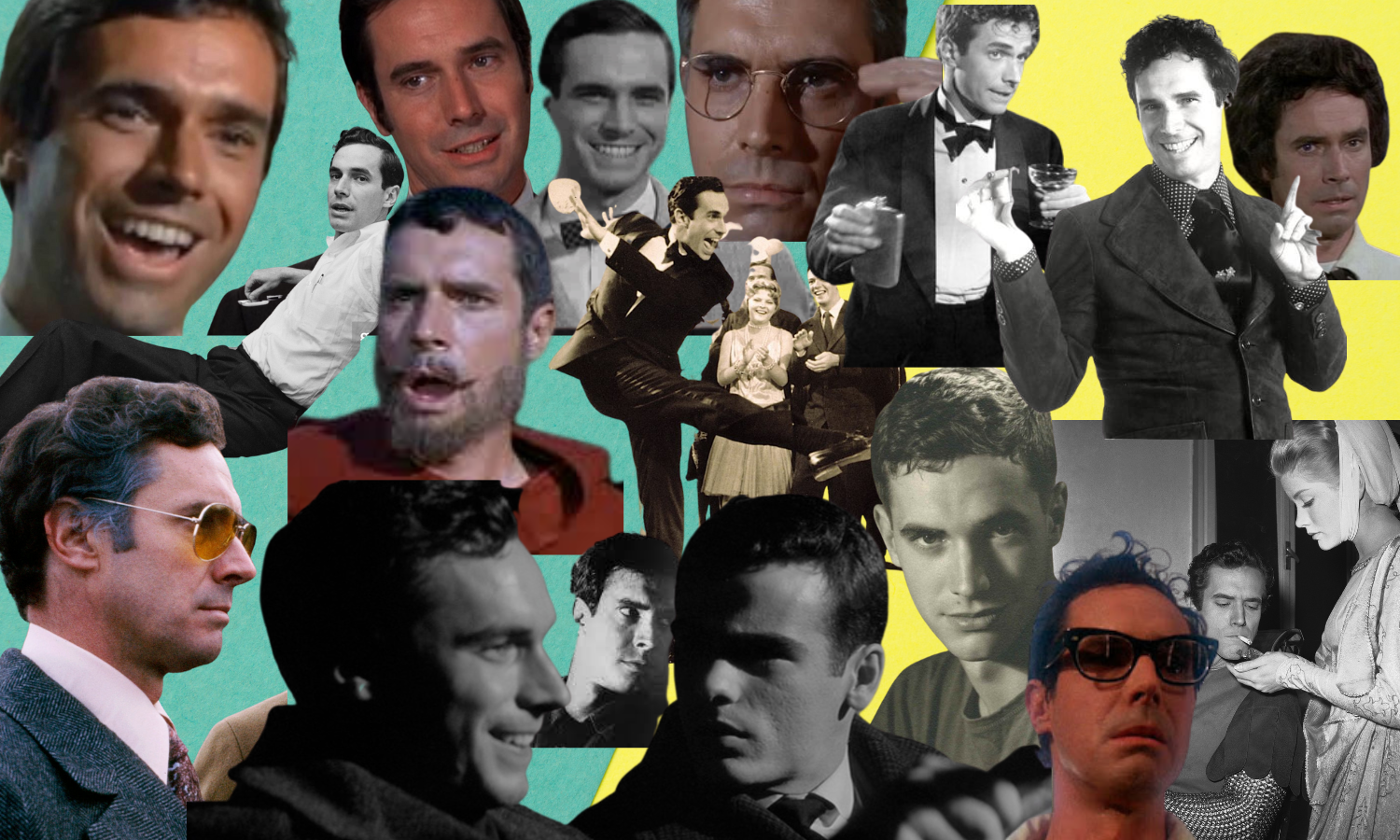

The Sinister Fun of Bradford Dillman

“By my reckoning, in over four decades I’ve been personally responsible for the demise of well over a thousand people. Heck, at Jonestown alone my Kool-Aid took out over nine hundred, and I’ve blown up the Queen Mary twice. Heroes are heroes. They pay the single greatest price of celebrity, the loss of privacy. This explains the army of bodyguards employed by some to keep the adoring multitudes at bay. Villains don’t have these problems. Me, I’ve never been bothered in a bar or boite. People can’t be sure I’m not carrying a knife or a gun.”

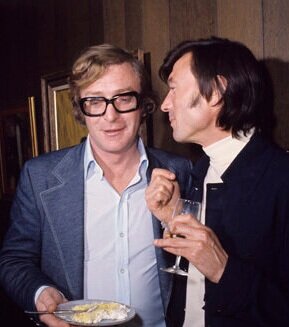

It is April, the sun is shining, and life is returning to some of our weary bones after what can only be described as a long, harsh winter of total discontent. In short, it’s Aries season, friends; and there is no better time to talk about charismatic villainous virtuoso Bradford Dillman (who would have turned 91 this April 14th). Bradford Dillman was an omnipresent actor in Hollywood for decades with a range that took him from The Actors Studio--debuting on stage with James Dean--and originating the role of Edmund Tyrone in the Broadway production of Long Day’s Journey Into Night to creature-feature horror and endless guest-starring roles attempting to kill the heroes in seemingly every 1960s and 1970s television program. He also kissed an ape in Escape From the Planet of the Apes.

Bradford Dillman is an heir to Peter Lorre and predecessor to Michael Shannon in the spectrum of actors giving us high-caliber sinister charm all mixed up with genuine emotional connection. He had the best evil smile in the business: a bent, slightly twisted smile that promised chaos--or at the very least some premeditated malice. His presence filled up all the empty spaces in every medium he appeared. A particular maximalist specialty of Dillman’s was the extended close-up on his face as it moved through dichotomous emotions--joy to rage; sadness to glee. He was acutely aware of movement in his face and body, but at the same time seemed to understand that he was supposed to provide an experience that was not quite human, more like human+. Why go out quietly, when you can go out screaming, howling, and/or cackling?

One of his early film roles was in Compulsion (1959), dir. Richard Fleischer, a fictionalized retelling of the Leopold and Loeb murder and trial. He played Artie Strauss (Loeb), a petulant 18-year-old rich boy who has never experienced a single consequence in his life and is convinced of his own superior intellect. He is as terrifying as he is charming, and his dominance over his (boy)friend as played by Dean Stockwell is the kind of performance that does not let you look away from it. Certainly not when he can be found carrying on an entire sinister conversation with a teddy bear. He shared the award for Best Actor at Cannes with co-stars Stockwell and Orson Welles (but not the teddy bear, which was a total snub). Compulsion is a film which is at times ethically dubious (for one, the murdered child is given almost zero consideration), but is at all times a work of performer-first filmmaking that builds a tremendous amount of tension, lets its actors run wild, and also contains a classic Welles’ fake nose (and fake eyebags?).

Dillman began as a method actor in important productions™, but since he and his wife Suzy Parker (supermodel; inspiration for Audrey in Funny Face) had a large family together, after she retired, he pivoted to being what he called a “Safeway actor”--anything to put food on the table. This is where he really shines: leaving a legacy of untrustworthy characters with intoxicating charm in every possible kind of film or television production. He was the man to go to for southern gothic werewolves or cult leaders or egotistical supervillains, and also sad dads or sweet dates-of-the-week for Mary Richards, or if you needed someone to play the nephew getting murdered by Uncle Ray Milland in an episode of Columbo. (My kingdom, my kingdom for an episode of Columbo with Bradford Dillman playing the murderer! Come on, Robert Culp and Jack Cassidy--stop being so greedy!)

One such unassuming production that got injected with Dillman was Jigsaw (1968), dir. James Goldstone. Jigsaw is a drug-trip murder mystery of uncommon chaos. (One wonders if even the film stock itself was laced with LSD?) It is also total fun, and perhaps even the platonic ideal of a sinister fun Bradford Dillman performance. He plays a repressed, emotionless scientist who wakes up with amnesia, blood on his hands, and in a room with a dead body. Suffice to say, the plot does later require him to trip on acid for ten minutes so he can remember (that’s how it works). The film was shot as a TV movie, but the content was too hot, so it got a theatrical release instead. Bradford Dillman has a great time, and the film plays up his unmatched ability to depict mania. Aside from the unfortunate use of a gruesome murder of a woman as essentially a plot mcguffin, this film offers perfect 1968 colorful+chaotic vibes.

That same year saw a theatrical release of another American television production with The Helicopter Spies (1968), dir. Boris Sagal, a two-part episode of Man From U.N.C.L.E. edited together as a single film for an international theatrical release. It contains an astonishingly fun performance from Dillman as the leader of a cult called The Third Way. Everyone in the cult (aside from him) is forced to dye their hair white blonde to match The High Priestess, while he wears an entirely white outfit (suit, shirt, shoes). Cult members greet each other by saying, “Keep the faith!” while offering a thumbs up. Naturally, he has plans to take over the world, charms absolutely everyone into believing him (including our two heroes), and goes on scamming. Because it is Dillman, we are never quite sure whether he is maliciously scamming for power and using the cult as a means; or whether he is maliciously scamming for power while actually believing in the cult. Delicious!

It is that level of morally unstable character (to borrow a line from The Naked Spur) that makes even supporting performances in films like Five Desperate Women (1971), dir. Ted Post, so much fun. The titular women are Joan Hackett, Stefanie Powers, Anjanette Comer, Denise Nicholas, and Julie Sommars. They are college BFFS reuniting on a private island cabin after five years--and they are a "mess" (some of them don’t even have husbands or babies yikes!). The chemistry between the women is genuinely perfect, and is a great intersection of heartfelt and camp. What we know, but the women do not, is that a murderous man is currently loose in the area. Naturally, our suspicion falls on Bradford Dillman as the boat captain who ferries them over to the island. He is a real weirdo and alienates them all almost immediately by explaining nutrition and how they clearly do not understand health like he understands it. Bradford Dillman keeps us dancing the whole time on the power of his sinister reputation alone.

This reputation for crafting exceptionally twisted...but fun characters (imagine I am saying that in a Sullivan’s Travels-like “with a little sex in it” cadence) kept him employed for decades. One of his final films was the Roger Corman-produced Lords of the Deep (1989), dir. Mary Ann Fisher. Honestly, this film is weird and freaky--and worth it for the wild camera work and special effects alone. It opens with a title card letting us know the year is 2020, and “Man has used up and destroyed most of Earth’s resources.” *gulp* Bradford Dillman is the good company man who commands a huge corporation’s experimental underwater habitat. He is a sinister capitalist who will see everyone dead before losing a drop of profits. He slithers around saying things like, “Are you imPLYING that I would endanger the lives of MY crew?” and “We used to have a thing called an Ozone, Jack. Remember? ... You idiot.” It had been thirty years since Compulsion, and he had not lost an ounce of his ability to terrify and charm in equal measures.

These five films I have picked practically at random, and they do not even begin to touch on the levels of delight to be had in Bradford Dillman’s 40-year, 142-credit film and television career. (These five are all available on streaming, however. I would especially give a look toward searching these titles on YouTube, ahem.) You can choose any one of his 142 performances and find something to shock, awe, and/or entertain you.

And, he certainly did not always play the bad guy (not even in all of these five films), but just as his villainy was multifaceted--his goodness was complicated. Suspicious, dark, twisted and bent like his famous smile. The man knew how to show us a good time.

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 04/05/2021.

-Meg

An Ode to Sandra Dee

Let me paint a picture for you: It’s 2008, and I am 14-years-old, and newly attending a local homeschool co-op that meets every Monday in a church that’s forty minutes from my home. A homeschool co-op is an educational construct in which a bunch of homeschool moms (and it’s always moms) create their own insular school system and then teach the children of the other moms so that the art moms can just focus on art, the theology moms theology, the founding fathers moms the founding fathers, and the one mom who is really good at math tries to explain calculus to a bunch of teens who had taught themselves how to add and subtract and multiply and divide. There is no science mom.

This is as close to a classroom or school setting as I had ever been at the time, and I was delighted by the concept of school supplies at last (oh, how I had coveted those overflowing bins at Target), and naturally, immediately decorated my class folders with photos printed out at the public library. I had a James Dean folder, a Grace Kelly folder, an Audrey Hepburn folder, an Ingrid Bergman folder, and a Sandra Dee folder.

On that first Monday, the teacher-mom for the Sandra Dee folder class (it was something like American Citizenship 101) asked me who was on my folder. I said with enthusiasm, “It’s Sandra Dee!” This was a few months before I started my film blog, and I was eager for any outlet to talk. In a move that prepared me for every internet-splainer to come, teacher-mom responded, “No that isn’t Sandra Dee. Sandra Dee is a character in Grease. ‘Look at me, I’m Sandra Dee…’” (She did not finish the lyric, which clearly was a spectre from her heathen youth, as Grease was not co-op approved.) I was torn between knowing that adults should never be corrected, and also by knowing that, well, it was Sandra Dee on my folder. I went with a mumbled, “This is Sandra Dee, the actress.” Teacher-mom said, “No, you must be confused.”

And that was that. I saw no path to victory, but internal fuming, and going home and turning on my library’s DVD of Gidget (1959, dir. Paul Wendkos) that was on semi-permanent loan to me, and watching Sandra Dee prove all her doubters wrong.

Sandra Dee on-screen always proved her doubters wrong. And it was exactly what I needed. She remains one of my favorite people to return to on film: a friendly cinema companion. Her presence carries a quality, a tangibility, a gravitas that has never been allowed to be attached to her name by critics or public opinion. Lucky then that Sandra Dee did not need permission to be indelible.

She is unmistakable onscreen and entirely irreplaceable. The Gidget sequels are enough to tell you that. I mean, look, I am one of the bigger supporters of Gidget Goes Hawaiian, and yes, I did once tell Carl Reiner that Gidget Goes Hawaiian was a great film to which he responded, “No.” But, Deborah Walley as Gidget is just filling space. (And we do not talk about nor acknowledge Gidget Goes to Rome.)

Sandra Dee’s Gidget is alive, so fully alive. She is energy and enthusiasm and vulnerability and confusion and angst and elasticity. Her triumph in learning to surf feels like an earned triumph and the joy is palpable, and equally her scenes late in the film with Cliff Robertson’s predatory Big Kahuna are genuinely distressing because of her performance and her efforts. While Sandra Dee’s work is often tossed away as light-weight and sterile based on some historical collective false memory, her performance in Gidget should really be considered a direct predecessor to Elsie Fisher’s recent acclaimed work in Eighth Grade (2018). Sandra Dee gave us a realistic vulnerable yet determined teen girl who absolutely triumphs (with the loving support of her teen girl BFF) and teen girl me said, “You love to see it! Can you please ditch Moondoggie though? He is a drag.”

Sandra Dee’s known public image today and her original popularity was definitely predicated on her fulfilling some sort of white wholesome teen girl ideal for a 1950s American audience, but conversely her characters are boundary-crossing troublesome girls and young women. A defining characteristic across so many of her roles is a refusal to conform--in small ways and big.

In The Reluctant Debutante (1958, dir. Vincente Minnelli), only her second film, in the midst of swirling mania, she is the cool one--observing the hysteria with bemusement and maintaining her personal sense of self throughout. She assuredly partners with Kay Kendall and Angela Lansbury with a level of confidence that astounds. Her comic timing is already excellent here, and so is her ability to work ensemble. Her most perfect ensemble obviously being Come September (1961, dir. Robert Mulligan), a film that is surely one of the reasons cinema exists as a visual art medium. Sandra Dee and her tangibility are vital. With all due respect to the blonde youth actresses of the 1960s (I love many of them), how many of them would have the precise energy to match so comfortably on-scene with peak powers Gina Lollobrigida and Rock Hudson? There is a scene in which she psychoanalyzes Hudson that is masterfully funny. Her scenes with Bobby Darin are equal parts tentative and confident; sweet and confused. And with Gina Lollobrigida, she is sincere and kind with immediate rapport. There is no danger of fading into one-half of the obligatory forgettable youth B-couple of the movie--even in the presence of the dazzling Lollobrigida and Hudson.

The other two films in the Sandra Dee-Bobby Darin trilogy are also particular fun--with outlandish plots. In If A Man Answers (1962, dir. Henry Levin), she decides to change Darin’s behaviour with a dog training manual, and in That Funny Feeling (1965, dir. Richard Thorpe) via some classic mistaken identity she convinces him his apartment is actually her apartment. She is the firm center, sweetly spinning Darin and the rest of the film around in circles of befuddlement while she decides what she wants and when.

This aura of self-autonomy made Sandra Dee one of my figures of aspiration as a girl. In her characters, she lets the audience see the process of doubt and vulnerability while also making the decision. Her way of speaking is memorable: sometimes halting with clipped sentences and sometimes too many words spoken too quickly, but she really does always keep speaking.

Her openness onscreen is definitely why young me always preferred to rewatch her comedies rather than her melodramas--the vulnerability was too real. I have a very vivid memory of watching A Summer Place (1959, dir. Delmer Daves) as a 12-year-old hoping it would be another Gidget and my dawning horror as the melodrama played out. Sandra Dee played yearning angst and vulnerability so acutely--it hurt me. I must confess I have never rewatched the film, and to this day, hearing that wistful theme tune is enough to re-traumatize me.

Sandra Dee played Lana Turner’s daughter twice, most famously in peak melodrama Imitation of Life (1959, dir. Douglas Sirk), and again in the seedy Portrait in Black (1960, dir. Michael Gordon). Dee and Turner match up perfectly, both so adept at playing girls and women grasping for self-autonomy and self-preservation in a world that has no intention of making it easy. I wonder if Sandra Dee’s career had continued past her 20s if she would have found herself in Lana Turner-like roles?

Instead her final film appearance came in 1970, at the age of 28, in The Dunwich Horror (dir. Daniel Haller). She plays opposite another former teen-actor-with-substance Dean Stockwell in a freaky tale of the occult and monsters that feels subtly template-like for many films that followed. Her soft vulnerability amidst the chaotic production stuns. In Sandra Dee’s hands, Nancy is not a stupid, gullible woman led easily into danger, but an open and empathetic woman trying to balance danger against desire: a navigation that is true in every day life even when your job and studies do not include the possibility of your body becoming a gateway vessel for demons.

Oh Sandra Dee, I wanted to compose an ode to you, but I do not have all the words I need.

Oh Sandra Dee, you’re not a pastiche of people’s false memories, a relic from a plastic era, or the line from a song-- instead, resolve and humor, humanity and kindness, and an absolute knowledge of the ridiculousness of life--it all showed up on screen and bolstered a girl who desperately needed to see another girl triumph. 💖

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 09/05/2021.

-Meg

QUIZ: Who is Your Classic Film Character Summer Fling?

I love a personality quiz. When I was a kid, I lived for the quizzes in my American Girl magazines. Which kind of dog are you? What famous female athlete are you? What kind of cheese are you? It did not matter. I wanted to answer the questions, and then proudly know that I was unique. I was not like other girls. I was a border collie (as true now as it was then).

We’ve reached the highpoint of summer. Heat domes all over the place. Honestly, too much sun, if you ask me. (No thank you, sun. I’m good.) The time is right to kick back with a cold beverage and take my little quiz and learn who your perfect classic film summer fling is going to be (oooooooh)....from the 7 options I am giving you (to be frank, they were the ones top o’ my mind, and all delightful characters).

Here is how it’s going to work: as you go, write down the number of your answer to each question, and at the end, add up your answers to find your perfect partner for this season. Aka if you answer mostly 1s, then 1 is your summer fling or mostly 5s, etc. I have included an answer key at the bottom. If you’re more love ‘em and leave ‘em, then consider a ranked choice system to come up with your top three beaus!

QUESTION ONE: It’s summertime! It’s time to take a holiday. You’ve been working hard, and you deserve a break. Your ideal vacation is______.

1. Kicking it back in an Italian villa. You like to spend your time in luxury, and you are not looking to do much else but chill out. Maybe a vespa ride around the countryside or a dance here or there, but mostly you like lounging out in the sun.

2. Taking a trip on a sailboat. You don’t even mind working as crew–you just want to get out there on the waves and experience that freedom that only the open ocean can provide.

3. Staycation! You live in the big city, and you enjoy your life. There is always something new to do, or explore. You do not need to go anywhere to relax.

4. Nothing planned. You are all about spontaneity. You pick a new place to visit and just go exploring. You are sure you will find an adventure.

5. Not a family vacation! You are trying to get away from your family, not spend more time with them.

6. On a train. You love to travel by train and stop off along the way throughout the countryside and little towns. Hiking, running, scrambling over rocks–anything that gets you outside and active.

7. VACATION? Who has time for vacation? You do not. You have things to accomplish, and nothing else matters.

QUESTIONS TWO: Ahh food! There are few things better in the world than sitting down to eat your perfect meal. The food you crave most is____.

1. Italian food paired with a perfect wine.

2. Well, food does not really satisfy you in itself–but you love an experience. You have always wanted to have a real picnic!

3. This little Japanese restaurant down the street that has an incredible, authentic menu.

4. Whatever food is right in front of you! You love to feast and feast and feast. You keep snacks next to your bed–just in case–and a jar of pickles is never unwelcome.

5. A home-cooked meal from someone you love. It does not matter what it is, it is worth all your money.

6. Simple fare. Anything that is easy to find along the road. You love a sandwich.

7. FOOD? Who has time for food? You do not. You have things to accomplish, and nothing else matters.

QUESTION THREE: What is the most played song on your playlist?

1. "Mambo Italiano" by Rosemary Clooney

2. "bad guy" by Billie Eilish

3. Anything new and avant-garde.

4. "I Love It" by Icona Pop

5. "I’m On Fire" by Bruce Springsteen

6. "Run for Your Life" by The Beatles

7. You don’t listen to much music, but you love to sing. People always know you’re around when they can hear you singing.

QUESTION FOUR: What was your favorite game to play when you were a kid?

1. Musical Chairs. You love group games, dancing, and making sure everyone is having a good time.

2. Wink Murder. No one ever guessed it was you even though you drew the murderer card every time.

3. Anything you could make a bet on. You knew how to win and make money from a young age.

4. Games with rules are boring. And don’t even get you started on board games: you get tired of them easily and tend to flip the board!

5. Spin the Bottle. hehe.

6. Hide and Seek. You were always the best.

7. Clue. You are clever, patient, and determined. You always found the murderer.

QUESTION FIVE: What is your favorite animal?

1. Definitely not parakeets.

2. Sharks. You saw a group of sharks attack an injured shark once and have never forgotten the spectacular sight.

3. Anything wild and free. No domesticated cats.

4. Honey Bees. You're here for a good time, not a long time.

5. Geese. When you've found the right partner, you're in it for life.

6. Foxes. You love their cozy little hidden dens.

7. A lone wolf. You admire their ability to track and hunt.

QUESTION SIX: What is your greatest fear?

1. Not being taken seriously.

2. Not getting to see the sunrise one last time.

3. Getting trapped.

4. Being bored and/or running out of snacks.

5. Being disrespected.

6. Someone telling lies about you.

7. Not fulfilling your purpose in life.

QUESTION SEVEN: You’ve been shipwrecked and stranded on a desert island, but you managed to carry two items with you from the sinking boat that you knew you needed to survive. Those items are_____.

1. A portable two-way radio and signal flags.

2. A knife and a gun.

3. An inflatable lifeboat and a compass.

4. A pair of scissors and a large jar of pickles.

5. Flint and a first aid kit.

6. A tarp for shelter and a machete to cut open coconuts. I guess you live here now.

7. Does it matter? You’ll figure a way out.

QUESTION EIGHT: Your favorite way to interact with other people online is___.

1. You are on every app at all times and have literally thousands of devoted fans, errr, friends.

2. Twitter. It is both the source of your sickness and its only antidote.

3. LinkedIn. Professional use only. The real life is happening offline.

4. Tumblr, baby! You know how to curate!

5. Exchanging numbers with your Tinder matches and then texting for 12 hours straight.

6. Signal messaging via burner phones only please.

7. You do not really have time for this, but okay, you sometimes post cryptic yet wistful poetry on your old LiveJournal. It reminds you of a different time when you were younger and happier.

ANSWER KEY

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 1's....

Your summer fling is Lisa Fellini as played by Gina Lollobrigida in Come September (1961). You are fun and flirty and a great communicator. You love to socialize and everyone sees you as the life of the party. You know what you want and you have great boundaries. Enjoy riding that vespa around the Italian Coast with the most beautiful woman in Italy. She demands respect, honesty, and commitment–so do not mess this up!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 2's....

Your summer fling is Elsa Bannister as played by Rita Hayworth in The Lady from Shanghai (1947). The people that know you would say that you are intense. But they also cannot look away from your allure. You are mesmerizing and totally misunderstood (but also a little evil, sorry!). Your cynicism is a good match for Elsa, and you both are not expecting more than you can offer. You and Elsa are either going to have a great summer or immediately break up. Hard to say, but it will be a wild ride while it lasts! Good luck!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 3's....

Your summer fling is Jack Parks as played by Sidney Poitier in For Love of Ivy (1968). You are independent and reliable, and undeniably cool. You know all the best places to eat and hang out. You live in the city and you love it at every hour–day and night. Just like Jack, your community is important to you, and you work hard to make sure the people around you are taken care of each day. You and Jack are both not looking to settle down…or are you?

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 4's....

Your summer fling is Marie I and Marie II as played by Jitka Cerhová and Ivana Karbanová in Daisies (1966). You are chaotic, unpredictable, and totally vibrant! You are not big on plans and love to take each day as it comes. You deeply understand the futility of society and choose your own path of joyful nihilism. You absolutely do not like to be left alone for any amount of time, and neither do the Maries! Get ready for a summer of feasting, snacking, and decadent food fights. Grab a baguette and jump in–the milk bath temp is wonderful!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 5's....

Your summer fling is Clara Varner and Ben Quick as played by Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman in The Long, Hot Summer (1958). You’re intense and focused, but also a hopeless romantic. You have high standards and a great deal of self respect. You are not going to settle for anything less than the best, but once you have your sights on the best–watch out! Clara and Ben saw you from across the bar and liked your vibe…

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 6's....

Your summer fling is Richard Hannay as played by Robert Donat in The 39 Steps (1934). Frankly, you have a lot going on. You are a busy person always on the go, go, go. A natural traveler, you feel comfortable in every situation and circumstance and you make friends easily. There is nothing quite like a scramble over the rocks or a walk through the moors, and you do well outdoors. Although incredibly likable and adaptable, you and Richard both tend to hide your true selves and have trouble trusting other people. This may make your relationship a short-lived one, but if you can find a way to let each other in–maybe you go the distance together!

IF YOU ANSWERED MOSTLY 7's....

Your summer fling is Tetsuya "Phoenix Tetsu" Hondo as played by Tetsuya Watari in Tokyo Drifter (1966). You do not have time for a relationship, as you are all-consumingly focused on your life’s mission. Everything else fades in the background. You must complete your task; you must fulfill your purpose. You are lonely, and although you might sometimes seem like a hard-hearted island of a person, you are actually very tender and gentle in your soul. There is a real softness about you, and if you could just be free of your work–free of your drive–you know that you would choose a very different life. Tetsu is on a parallel path as you, and together maybe you finally accomplish that

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 08/11/2022.

-Meg

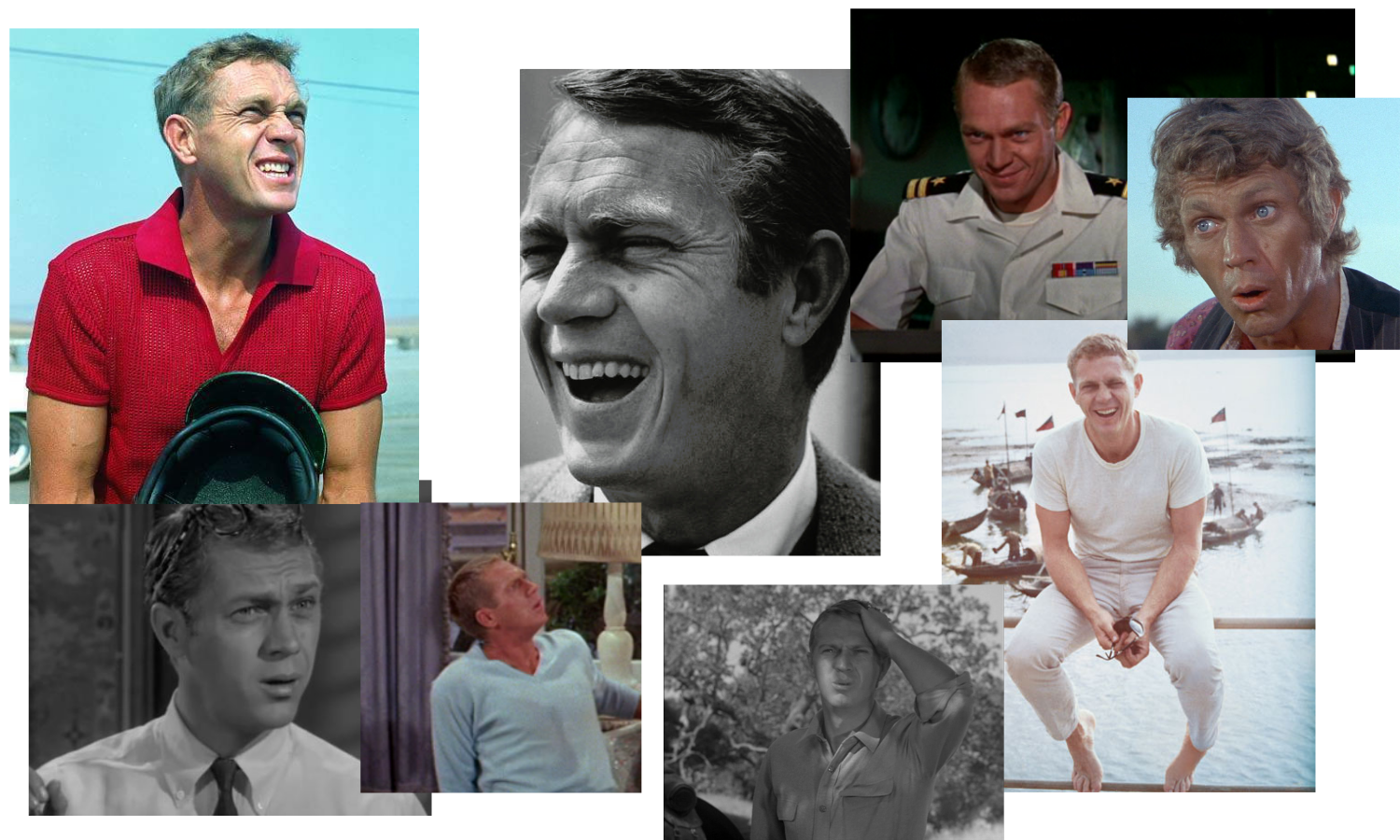

Steve McQueen, Cinema Goofball

Popular culture remembers Steve McQueen as the King of Cool, a paragon of stoic masculinity, a laconic man of few words and fewer emotions. But, what of the other side of Steve McQueen’s on-screen persona?

Popular culture remembers Steve McQueen as the King of Cool, a paragon of stoic masculinity, a laconic man of few words and fewer emotions. The remembered idea of him is two-dimensional, and–as a marketing scheme–highly successful: his name appears regularly in the lists of the most profitable dead celebrities. He is an image: stern, unflinching, immovable, untouchable. He doesn’t crack under any pressure, just like a Tag Heuer watch. He is “The Absolute Man” according to the vodka brand.

But, what of the other side of Steve McQueen’s on-screen persona? Not the vroom-vroom car chases and cool sunglasses and dialogue-free scripts. Not the decades of co-optive advertising. The other side: the much-maligned (but much-beloved-by-me), entirely uncontained, earnestly unsure total goofball.

I came to Steve McQueen early in life. He is my oldest brother’s favorite. Five years older than me, this brother always had a Steve McQueen movie playing, or a DVD lying about. My understanding of McQueen was formed first by the television series Wanted: Dead or Alive. And yes, he does play a cool loner bounty hunter traveling through the American settler west of the 1870s. But, his Josh Randall is also deeply connected to the people he meets along his travels, always getting involved, solving troubles, and occasionally forced into absolutely wacky shenanigans.

Burned into my memory, is an episode from the final season released in 1961, titled “Baa-Baa.” Josh Randall is sent in search of a lost pet sheep, there’s a singing chorus, montages of him chasing sheep over hills, and pratfall face grimace combinations not seen since the days of Cary Grant flying through Arsenic and Old Lace. That is my enduring image of Steve McQueen: flailing and just a little earnest.

I have written bits and pieces before about Steve McQueen’s depiction of masculinity. It fascinates me. It never seems to me to be the confident, unbreakable idea that endures from his most famous roles, but in actuality rather fractured and unsure, as if he was precariously holding himself together. Often the only outlet of emotions in these performances is violence. Once stardom took hold, there was an increasing unwillingness on-screen to divert from tightly-contained emotions and limited dialogue; almost as if to open himself up at all would be the end of his control.

This is a marked difference from some of the other enduring cool guys of the era, like Sidney Poitier, Toshiro Mifune, or James Garner. Their self-confidence felt entirely real and fully true to themselves in every kind of film or performance. James Garner was good pals with Steve McQueen, but also had this to say in The Garner Files, “He was a movie star, a poser who cultivated the image of a macho man. Steve wasn’t a bad guy; I think he was just insecure. … Deep down, he was just a wild kid. I think he thought of me as an older brother, and I guess I thought of him as a younger brother. A delinquent younger brother.” (Note: This is also what happens when you put two Aries together, I say as an Aries.)

That delinquent younger brother energy is a dominant theme in all of Steve McQueen’s “b-side” films: those films that do not comfortably fit into his steely iconography, and are left out of all the advertising and the cool montages.

Steve McQueen’s best performance comes in one of these films, Love with the Proper Stranger (1963). A romantic drama permeated with sweetness, it is McQueen’s softest role. His co-star Natalie Wood is glorious, confident, and self-assured even while her character is facing extraordinary fears and pressures. McQueen plays his character hesitant and awkward. He is a cool-cat jazz musician who trips over and mumbles his words and hunches and slouches his body. The finale of the film is the ultimate goofball gesture–and stunningly earnest.

Sometimes, Steve McQueen’s ventures into goofball territory are far less earnest. The Reivers (1969) is a film I would charitably describe as YIKES (but what a supporting cast! Rupert Crosse! The great Juano Hernández!). It is also a strange amalgamation of his competing film energies. There is the obsession with a car and emotions processed via violence (particularly directed at women), but there is also slapstick slipping in the mud and very big reaction faces. There is an internal battle for his performance soul warring throughout this film, and violent goofball is not really a comfortable spot to land.

Critical and public appraisal of McQueen’s ventures outside his narrow sphere has never been laudatory. Anything he did that came close to comedy has been thrown out in confusion with a note that it is “really not his thing.” Yet the problem with The Reivers is not the earnest comedy, but the elements of coldness and violence. Steve McQueen’s image sells luxurious watches under the promise that he doesn’t crack under pressure. Ice cold silence sells. Flailing limbs and high-pitched scrambling does not sell vodka--apparently!

Yes, the time has finally come to talk about The Honeymoon Machine (1961). This movie is bonkers, but with that impeccable internal logic that makes 1960s comedies run so smoothly in their own wild realities. It is also peak goofball McQueen. As a scheming sailor with a plan to game the roulette wheel in a Venice casino using a naval computer, he talks extraordinarily fast–often at a high-pitched squeak–and says more words than most of his other films all put together. He stumbles and trips and sways. He is a delight. He hated it.

He walked out of the first preview, and said he would never work with MGM again.

I think it is one of the most endearing McQueen performances. To watch him play a James Garner comedy role without James Garner levels of self-assurance is such a feat of sincere effort. He pulls it off too, because it is all McQueen. He may be playing a zany goofball, but the threat of violence feels ever-possible as he hops about manipulating everyone around him and talking about Nietzsche.

I love Steve McQueen’s on-screen work. 12-year-old me somewhat unconsciously attempted to model my stride on his after watching that long opening shot of him walking down the street in The Cincinnati Kid. His Vin in The Magnificent Seven is one of my favorite characters dear to my heart. His work as Sweater Detective in Bullitt is an aesthetic triumph. Wanted Dead or Alive fills my soul with joy (and I once wrote a piece about its fashion when I was 17). That episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents where he bet Peter Lorre his finger is a lesson in building tension in 25 minutes (I also love that episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents where he is a goofball Martian).

But, my understanding of Steve McQueen is not an image used to sell watches and vodka and cars. My Steve McQueen does sometimes crack under pressure. Sometimes, Steve McQueen was bold, violent, cold, angry, and harsh–causing pain that ripples. Sometimes, Steve McQueen was fractured, unsure, flailing, earnest–looking for a safe route to just be. Sincerity even in its tiniest measure is a hard-won human triumph! Long live the sincere goofball cinema of Steve McQueen! (Maybe don’t watch Soldier in the Rain though.)

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 01/10/2022.

-Meg

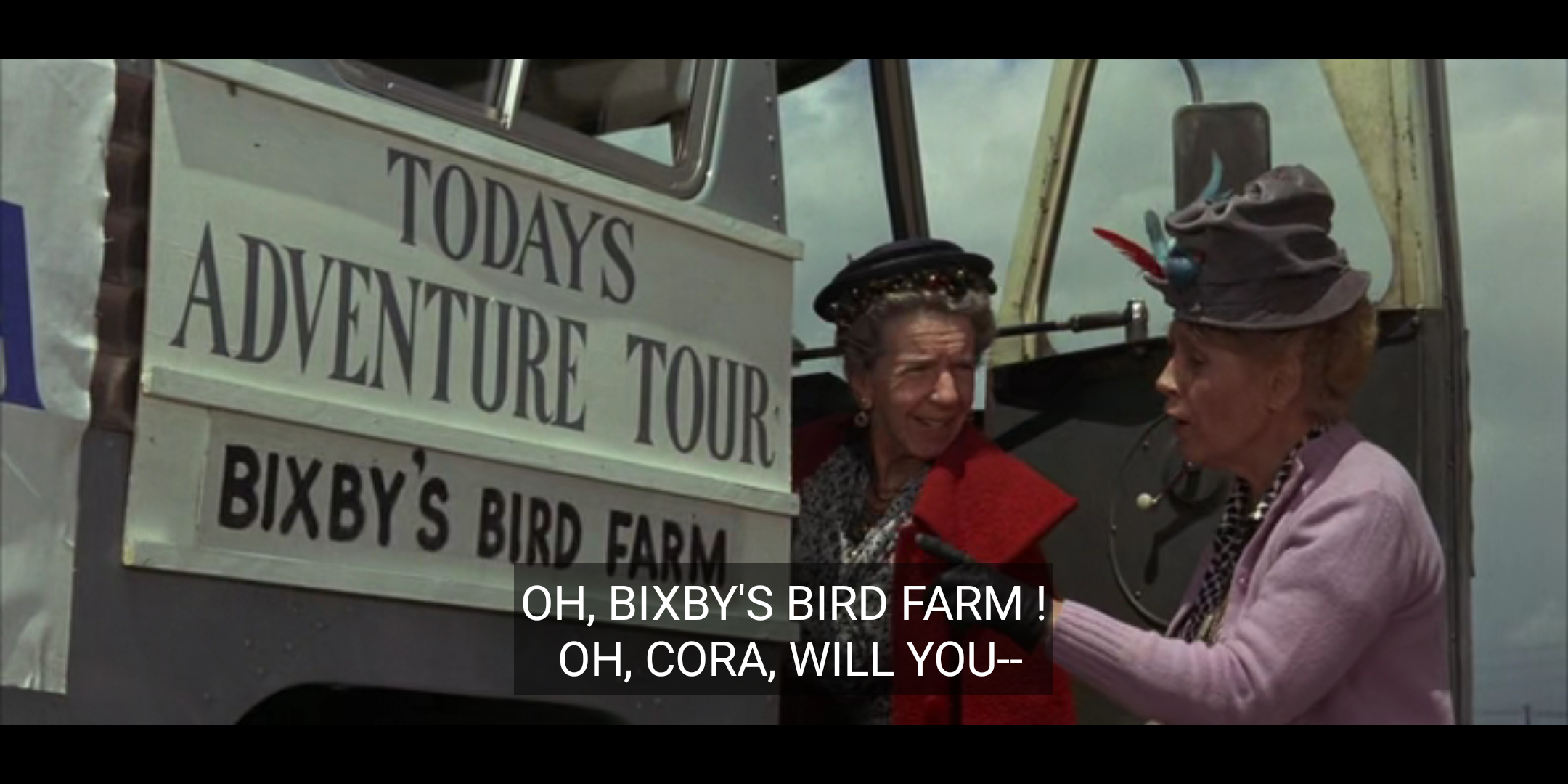

Bikini Beach (1964) or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Embrace Joyful Nihilism

Bikini Beach // dir. William Asher // United States

Bikini Beach // dir. William Asher // United States

We have had more than one successive day of sunshine here in Seattle, so yes, I am calling it: SUMMER IS HERE! As with many things in life (I resisted adding a heavily sighing “these days”), summer is more of a vibe than an actual tangible construct. So, to celebrate that, I want to celebrate a film that truly understands why vibes are more important than tangible constructs.

Bikini Beach (1964), dir. William Asher, is basically the third in a nebulously numbered series of Beach Party films (whatever the true number of films in the collection is--I’ve seen them all), and it is also the best film of the entire series.

(Quick vibe-check: if you think the best Beach Party film is Beach Blanket Bingo, respectfully, please either keep that to yourself, or quietly exit today’s lecture--thank you!)

Its status as best is perhaps based entirely on the initial determination of my 14-year-old self, but I truly do trust that 14-year-old me remains the best judge of 1960s teen surfer comedies, so we are running with it.

14-year-old me is also where our story begins today, as that was my age upon first viewing this cinema treasure. It was 2008, and back then, Hulu used to have an entire library of ~underappreciated~ 1960s movies to watch for free without subscribing (reach out to discuss Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine at length anytime). I saw this, and quickly showed my childhood best friend and it entered the sleepover rotation, and the rest is history, and I am definitely going to text her “Oooh Bixby’s Bird Farm!” as soon as I am done typing this up--and she will immediately get it.

There is something to the fact that all these films were made by American International Pictures (all hail cinema) very quickly and very cheaply and intended to be direct-to-the-teens movies, and somehow that strategy was still holding up and working out forty-five years later.

The formula works, because it is basically all bright colors, sight gags, and occasional footage of stunt surfers wearing visibly fake Annette wigs. More to the point, the formula works, because Annette Funicello + Frankie Avalon really are fun and charming onscreen. Their performances are truly enjoyable, and they have sweet, friendly chemistry together (I am not the first to say this, obviously, but consider it very Doris Day + Rock Hudson in the best ways).

In this film (and others in the series), Annette Funicello has the often thankless role of trying to get Frankie to think about his future, but she does so with a mischievous twinkle and a strong presence. She also really knows how to sing softly+sweetly while walking on a rear-projection beach at night-time, and I am not being ironic by saying that. It is an actual skill to inject so much personality and professionalism into formulaic, low-budget films. Plus, I have never stopped thinking about these pants.

And, Frankie Avalon in Bikini Beach? Well, let’s just look at the first note I scratched out while considering what I wanted to write here: “Tour de force Frankie Avalon the only good teen boy 60s actor.”

Those who know me well, will know that while I do enjoy frequently saying the phrase tour de force out loud, I do tend to truly reserve it as a description for work like Paul Robeson in Body & Soul, or Irene Dunne in The Awful Truth, or Tom Hardy in Venom. So, when I say Frankie Avalon’s dual role (!!!) as Frankie and as The Potato Bug is tour de force, I truly mean tour DE force. On that note, what I am about to tell you is going to make you reconsider trusting 14-year-old me as a cinematic arbitrator, but actually it should just reinforce the objectively career-pinnacle work Frankie Avalon does here.

So, Frankie plays two parts here. He plays “Frankie,” the lead youth who lives each day as it comes and regularly breaks the fourth wall to chat to the audience, and he also plays The Potato Bug, a British pop singer ala The Beatles as interpreted by Terry-Thomas (the accent and the gap tooth really give away that inspiration). At one point, “Frankie” dresses up like The Potato Bug to fool Annette, and shenanigans ensue. Anyway, yes, 14-year-old me--an already sophisticated film fan with a wide-range of film interests and deep well of films watched--did, in fact, think that there was a different actor playing The Potato Bug and that when “Frankie” pretends to be The Potato Bug in-film that it was just Frankie Avalon doing a convincing but not perfect impression of the actor playing The Potato Bug. AND YES, when the end credits scroll said,

Frankie Avalon as Frankie

Frankie Avalon as Potato Bug

I GASPED.

I still cannot explain this absolute lapse to you except that it was a tour de force performance.

Also, this bit of trivia was included in my Beach Party boxset: "Frankie Avalon's make-up and heavy accent were so convincing, visitors to the set were not aware that he was playing the role of Potato Bug." Think kindly of 14-year-old me. I was not alone in this.

Now that proper deference has been given to this iconic ringer performance, consider the other members of the cast. These movies have a structure that, along with the regular youth crew, includes an antagonist (usually older familiar actor), a sparring partner for the antagonist (usually older familiar actress), a guy running a hangout (usually a Don Rickles or Morey Amsterdam), and a surprise cameo guest from a true legend.

The reason Bikini Beach is the best of the series is that each necessary ingredient is there, but also actually good. In the original Beach Party, Robert Cummings plays the older familiar face role as a professor “studying” youth culture, and comes off as such a creep that even Dorothy Malone sparring with him cannot save the cringe. Here, however, we have Keenan Wynn--an actor who can slot in anywhere in any film and elevate the whole thing. He plays an unscrupulous land developer who is trying to turn public opinion against the surfers, so he can buy up land for his assisted living empire. He does this by bringing along his pet ape Clyde everywhere to prove that the youth are no better than apes. He offers gravitas and wit to a role that requires him to be chauffeured around by a person in an ape suit on rear-projection.

Here his sparring partner is Martha Hyer, a local school teacher who is hip and wants to advocate on behalf of the youth. She is great, and gracefully dances the Watusi with the aforementioned person in the ape suit. Don Rickles owns the local drag strip and the hangout and paints on canvases all over the bar. A strange older man, who is only visible from the back, keeps looking at the paintings but never buying. When his identity is revealed in the finale--it is a delightful surprise. I won’t spoil, but other films include cameos from Peter Lorre, Vincent Price, and Buster Keaton.

There is also the regular crew including Donna Loren (and her headbands!), Jody McCrea (exact replica of father Joel), Candy Johnson (fringeeeee), Stevie Wonder (still Little Stevie Wonder here), and--in typical inexplicable, but oddly obvious fashion--Timothy Carey playing a pool-playing, growling South Dakota Slim. Never let it be said that there was no edge to Annette + Frankie’s beach.

In fact, there is a bit of unsettled anarchy to these films. Certainly, there is a peculiar kind of lawlessness present. They never once address any big contemporary social issues, and they are almost uniformly white (and sometimes have casually racist elements like Buster Keaton playing a “native witch doctor” in How to Stuff a Wild Bikini), and they cannot be considered any sort of radical or counterculture art. However, they do offer pure, ungraded joyful nihilism.

There is a utopian element to Bikini Beach, with the unsupervised young adults living communally on the beach: sharing resources and experiences. They take each day as it comes, learn new things, and spend a lot of time dancing in the sand. The youth are mostly kind, or at least benign, and tend to solve individual problems by coming together. There are always hints that they know the world does not work that way, and so they just choose to ignore the world. In the ecosystem of the Beach Party, that works out for them just fine. They live outside of general society, and have created a new one.

In this society, plot, logic, and physics mean nothing. It is all vibes. 100 minutes of colorful vibes. There is no sight-gag too disruptive, and no innuendo too obvious, and no pratfall too chaotic to be included. There are chase scenes, a breaking up the bar fight, a little surfing, some drag-racing, and multiple musical numbers. Physics means nothing, but commitment to the film is everything. And, everyone involved was professionally committed to the silliness. Many years later, William Asher (director, co-writer, and essentially architect of the series) said about the “sheer nonsense” of the films, “The whole thing was a dream, of course. But it was a nice dream.”

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 05/05/2021.

-Meg

The World Ten Times Over (1963)

The World Ten Times Over // dir. Wolf Rilla // United Kingdom

Queer ladies living it up, loving each other, and surviving to the end of the film–IN 1963 BRITISH CINEMA?

The World Ten Times Over // dir. Wolf Rilla // United Kingdom

“People like us do what we want to do, not what people tell us to do.”

Queer ladies living it up, loving each other, and surviving to the end of the film–IN 1963 BRITISH CINEMA? Wolf Rilla’s film, The World Ten Times Over, is an unexpected and underseen delight. Shot on location on the streets of Soho in London, and anchored by beautifully tender and fun performances from Sylvia Syms and June Ritchie, this is a film that deserves to be seen and known.

Billa (Syms) and Ginnie (Ritchie) are long-time companions who share a flat and a bed, and both work as escorts in a local nightclub. The film follows a few days in their lives as Billa’s country-mouse father (William Hartnell) comes to town for a weekend visit and Ginnie navigates a sexual relationship with a wealthy businessman (Edward Judd).

Sylvia Syms, in particular, is extraordinary here. Two years after playing Dirk Bogarde’s wife in Victim--the first English-language film to use the word “homosexual”--she starred in this film, which the BFI considers to be the first implicitly lesbian relationship depicted in British cinema. (Syms remained a legend with her final role being in the 2019 queer television drama Gentleman Jack.) Syms has a screen presence full of that elusive star energy. When she is lively, she can be very lively. There is an organic joy to her work that is potent. And, when she is vulnerable, she can be very vulnerable. In this film, she plays the longing cynic Billa impossibly entangled with the effervescent and somewhat unreliable Ginnie.

They push and pull throughout the film, one or the other taking the lead in their relationship; both expressing a sense of fatalism, but Billa’s version is quietly resigned and Ginnie’s version is hedonistic. Ginnie wants to forget fate, and Billa can only remember it.

They are gentle with each other, and also cruel. There is a constant sense of external pressure looming and crushing. In their tiny studio flat, the shared bed prominently displayed throughout, they are free to exist without pretense or lies–except the ones they are telling each other to avoid vulnerability and rejection.

The film opens as it ends, and as much the film is spent: in their flat. Billa is returning from work late at night and calls out for Ginnie only to see their bed is empty and still made. The camera tracks around the apartment as she gets ready to sleep, catching all the little knick-knacks and photos, depicting a cozy shared home. The first shot post-credits is Billa gazing at a photo of Ginnie.

The film cuts to Ginnie in bed with the wealthy businessman. She jumps out impulsively refusing sex, because she doesn’t “feel sexy” tonight. They argue about his wife, she hops about playing piano and talking about his wealth. She smashes the piano keys with frustration and the film cuts to the next morning and Billa’s and Ginnie’s morning routine in the flat. Ginnie is in the bath reading newspapers and taking calls, and Billa is the housewife bringing her tea.

Their home is the location for many scenes of quiet intimacy throughout the film, and establishes their often-shifting relationship dynamics. Both characters have separate emotional breakdowns in their apartment, but in those moments the other rises to the moment to bolster and support and comfort. They are equals, sharing burdens and secrets and jokes and purpose.

They have lived and worked together for some time, but, as the film begins, the twin burdens of finances and their unsanctioned relationship are beginning to wedge them apart. As they argue over money and their relationship that first morning, Ginnie shouts impulsively, “I want out! OUT!” Billa, ever practical and resigned, replies firmly, “Out where?” There is no getting out or being out.

The film follows Ginnie as she flits in and out of considering a long-term relationship with the wealthy businessman. She extols her desire for wealth and the ability to have fun all the time–to run away and make a life a party–to run away and forget being trapped in a harsh society.

In a parallel track, we see Billa meet with her visiting father. She becomes increasingly frustrated that he refuses to see her for who she is in any way. His benign neglect and disinterest in her life pushes her to try to shock him with her work and her relationship with Ginnie. She blurts out, “She is going to leave. She’s going to, how do you say, live in sin.” His uncomfortable reply, “Of course, moral standards are changing–greatly. He follows this by asking his daughter, “I’ve always wondered if there was someone in your life, a nice boy?” The conversation and their relationship deteriorates quickly from there.

Interwoven are these scenes of Billa and Ginnie pursuing their relief from external pressures, and how they believe they will find relief: Billa through being known and loved unconditionally by her father, and Ginnie with wealth and the freedom from all societal constraints that it promises.

They keep returning to each other, shedding personas, and becoming vulnerable. Ginnie is unable to commit to a decision whether to join the man and his wealth or to stay. Billa is unable to bring herself to ask Ginnie to stay with her, but in Sylvia Syms’ hands, the open longing is tangible and ever-present. She is half agony, half hope (to borrow from Austen).

I am going to discuss the ending of this film, and specifically how it subverts tropes. If you do not want to have narrative plot points spoiled, I suggest we bid adieu for now. You can watch the film in its entirety for free here on Vimeo.

I also want to note content warning for a mention of attempted suicide.

Billa confesses to Ginnie that she is pregnant by one of her clients. Ginnie promises she won’t leave her, saying, “I may be a bitch, but not that kind of bitch.” Billa gleefully helps her evade the wealthy businessman who shows up planning to take Ginnie away to a tropical island. He is suspicious and antagonistic toward Billa, she responds breezily and they sneak out off to work and Billa stops to blow a kiss goodbye in his direction.

At their work, we see them at dinner with clients. They are playful and manic–in a scene reminiscent of Vera Chytilová’s Daisies (1966). Billa’s father shows up, but Ginnie gallantly defends her by trying to outrage and shock him.

While cackling on their way to the restroom, Billa suggests they raise the baby together. As she goes on happily, the camera follows a suddenly serious and terrified Ginnie. She abandons Billa to the clients and her father and goes to the wealthy businessman. Billa’s father ultimately leaves, but not before calling her “trash” in seeming final note to their relationship.

Ginnie finally makes her choice, and leaves the wealthy businessman, but returns home to Billa’s absence. She screams Billa’s name again and again. The film cuts and returns to Billa.

Billa stays at the club until the very end of the night, and brings another worker home with her. This woman has nowhere to sleep that night, and Billa offers her Ginnie’s side of the bed, because she believes Ginnie has left her forever. The woman goes into the bathroom, and discovers Ginnie bleeding from a suicide attempt. As the audience, we only see a limp hand, and the presumption is that Ginnie has died.

This outcome seems pre-ordained. Cinema is full of dead queer characters. The phenomena is perhaps best known as the trope Bury Your Gays. Even films sympathetic to queer people see a tragic death as the most logical or realistic conclusion due to “society.” Additionally, in films of this era, still somewhat bound by censorship boards and codes, any woman acting outside of true womanhood must either be returned to those constraints or be deeply punished. A tragic death is a fitting punishment.

Yet.

Ginnie has not died. Her attempt was unsuccessful. She has survived with minor injuries. The doctor bandages her hands, dismisses it as attention-seeking, and leaves. Ginnie is lying in their bed without expression or words. Billa freaks out, hurling her anguish at Ginnie, and screaming. The forgotten woman from the club breaks the tension, yelling, “She’s alright!” She then says that trains are probably running now and peaces out of being the unwanted third wheel.

What follows is a finale of incredible tenderness, as they both finally open their vulnerabilities completely. Ginnie wanted to die at that moment, she explains, because she came back to the empty flat and thought that Billa had left her. She had finally made her choice–life with Billa–but she thought it was too late. Billa holds her hand, touches her arm, finally they embrace fully. They face a life with obstacles no less surmountable than they had been days before, but they repeat together a single refrain directed at society, “Damn them all.”

Two promiscuous women, one pregnant and other shown having sex with a married man, well, they must be punished. The censor boards and the codes demand it. So, in a breathtakingly perfect punishment, the film delivers and subverts the most classic of cinematic punishments: the woman ending up alone and unmarried and unwanted by any man. The film says, here they are, fully punished. They have no man. They only have each other.

And, in a touch of grace and hope and fervent expectation of a future, the film ends with the sun rising, the neighborhood going about its daily routine, and one final shot: Ginnie stirring in their bed and turning to embrace Billa as they sleep on peacefully together.

The sun rises, they love each other, all will be well.

-Meg

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 06/05/2022.

“I am not loveable”: Laurence Harvey and the performance of self-presentation

“Someone once asked me, ‘Why is it so many people hate you?’ and I said, ‘Do they? How super!’ I'm really quite pleased about it.”

“Someone once asked me, ‘Why is it so many people hate you?’ and I said, ‘Do they? How super! I’m really quite pleased about it.’”

Laurence Harvey fascinates me as an actor. As someone who had a relatively low-impact career (and certainly a short life, dying age 45), his acting continues to inspire a remarkable level of divisive responses among film people™. I have never quite been able to figure out exactly why, but it does seem rather instinctual. And, I am not usually one to wade into film people™ fights without a firm ground. (You can find teenage me timidly acknowledging, “people either love him or hate him,” in a review of The Ceremony.)

Nevertheless, my first instinctual response to Laurence Harvey was absolute delight. I was maybe 11 or 12, and I saw his episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. It has stayed firmly planted in my memory from the pure audaciousness. It is quite gruesome and unrepentant. Harvey plays the titular chicken farmer named Arthur, a charming but basically anti-social figure. He opens by telling the audience, smiling, “I am a murderer,” and then narrates his story. He murders his fiancé, disposes of her body in the chicken feed, raises chickens on that feed, and eventually sends some gift chickens to an investigating cop. The cop is so enamored with the taste, he asks for a list of feed ingredients. Arthur obliges, turning to the camera to state smoothly, “All but one. I left out that one special ingredient that really made it.” There is no justice and there are no consequences. (Hitchcock does offer a cheeky closing statement about the chickens growing to an enormous size and then probably killing and eating Arthur.)

I was transfixed. His character, and the story, were certainly misogynistic (a common characteristic across many Harvey roles), but there was something that intrigued me: the utterly manufactured façade of a self-image he projected.

Around the same time, I unintentionally saw his episode of Columbo (released in 1973, just a few months before his death): he played an emotionless chess freak murderer. In this, his character is once again set apart from natural and expected human warmth and emotion. I said, “Well, well, well. Tell me more.” (Let us not delve into my childhood psyche nurtured on too much Hitchcock and Columbo, and the Beatrix Potter story in which Tom Kitten is almost turned into a roly-poly pudding by giant rats.)

From then on, I kept an eye out for Laurence Harvey (carefully learning, with a couple missteps, to differentiate his name in a cast list from that of the viscerally terrifying and despicable presence of Lawrence Tierney). What he had onscreen, I could never quite articulate in my blogging youth, but I understood it and was drawn to it.

His screen persona was always openly enigmatic. He never tried to hide the fact that he was hiding—hiding his true self; his true feelings.

I have always connected his depiction of masculinity with that of Steve McQueen actually. McQueen is held up in popular memory as some icon of masculinity in the same limiting and distorted fashion that Marilyn Monroe is held up as an icon of femininity. Of course, they were actually both much more—and infinitely more complex—than the shallow containment allows (more on the glorious Monroe another time).

McQueen’s depiction of masculinity is far more complicated (and interesting) than his popular legacy would suggest, and far more aligned with Harvey than immediately obvious. Just as Harvey’s characters were often steeped in misogyny, McQueen’s were often violent—uncomfortably so. But also fractured. As if the confidence to live and express himself only worked in a narrow, tightly-controlled sphere, and he better not say too much or change his ways too much—or everything might disintegrate.

McQueen’s characters distracted us from their internalized self-doubt with an erected façade of coolness. He looked cool, and did performatively cool things, and never said too much—so how could we say he was anything but supremely confident himself? The cracks showed through though. (And his own pal James Garner called him an “insecure poseur” in real life, which is blatant Aries v. Aries violence but I’ll allow it.)

Why have I taken a detour through McQueen to talk about Harvey? I think they both spent their short careers depicting unsafe men: men who correspondingly never felt safe themselves to just be. McQueen covered his characters’ fractures with uncannily good film choices and an ability to project coolness. Harvey never even tried to play his characters as anything but self-loathing.

in his directorial debut The Ceremony (1963)

Laurence Harvey played roles of disliked men; broken men; loathsome men. To them, he gave the brutal honesty of self-doubt and self-loathing, often coupled with the inability to articulate these feelings—or even to fully understand the feelings for themselves.

His most famously remembered role today is probably Raymond Shaw in The Manchurian Candidate, but it is both typical and atypical Harvey. Typical, in the sense that his character is pretty universally disliked by all the other characters for much of the film, and also his emotions are tightly controlled, cold, and hardened. But, atypically, Raymond Shaw can articulate what he feels and understands about himself. He just has to get a little drunk first to say, “I’m not lovable. Some people are lovable, and some people are not loveable. I am not lovable.”

In his characters, he captured the angsty longing of James Dean, but without the openness; without the bare emotions; without the yearning reach toward other humans. As a teen Dean devotee, my innate alignment with Harvey’s work makes perfect sense to me. It appeals to the unconfident child with plans to show themselves to the world within a carefully chosen and constructed presentation.

It is a tricky business transposing screen persona over a fully-formed human person—and I really try to steer away from that in the general sense (*everyone ever trapped in a text thread while I discuss my favorite performers is now laughing heartily at this statement*). I do not know enough about the short life of Laurence Harvey to exhaustibly essay on it, but all due consideration to the death of the author, I can tell you why his screen persona—which often slotted in with his projected public persona—compels despite its carefully structured coldness.

His Joe Lampton in Room At the Top is fully concerned with the work of self-presentation. How can he react to the trauma and pain of life in a way that gives him strict control and power over his image to others? Of course, in this film, his image control is primarily routed through destructive and deeply misogynistic interactions with women. The self-loathing is strong here, and so is the childhood trauma. (He even steals a beat from James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause writhing-in-turmoil-with-a-toy-in-the-street performance near the end of the film.) The story concerns itself with the catastrophic ills of classism, and wealth’s casual habit of ignoring, dismissing, and then crushing to dust any would-be rebels in the system. Truly, an evergreen subject.

I recently rewatched this for the first time since my own angsty teens, and I was struck pretty much the same: adoration for the resolute clarity Simone Signoret gives her Alice, and a resigned *yikes* floating in the general direction of Harvey’s messy, messy Joe.

Joe is truly so very unlikeable in his attempts to beat his oppressors by becoming them. Harvey’s performance here works as a sort of thesis for his entire career of characters: resolutely individualistic, powered by self-loathing, somewhat irredeemable, yet still lit with a spark of uncanny energy. In every film, he was never anything less than calmly chaotic.

(his characters can oscillate between chaotic neutral and chaotic evil—but rarely even begin to whisper at a hint of chaotic good)

This is true even if you watch his early cinema work in England when he was more than once cast as some sort of charming rapscallion, life-of-the-party (perhaps more in line with his public self: a jet-setting, stylish Elizabeth Taylor BFF who managed to clash with seemingly every single introverted/subdued/serious actor he ever worked opposite). It is wild to see him play characters like the scamming talent agent in 1959’s Expresso Bongo (a fever dream of a film co-starring my very lively personal fav Sylvia Syms): a character who is likely intended to be seen as a troublemaker, but a fun one—yet in Harvey’s hands comes across as a somewhat unhinged menace.

This character type is a menace! It’s the archetype selfish conman who is always making plans to make money and treats the woman who loves him like trash while he’s bouncing off to another probably illegal scheme. Cinema is rife with them. Often, they’re a lot of fun to watch. Other actors use their own reserves of personal charm to smooth the rough edges; to make these loathsome men appealing. Instead, Laurence Harvey barrels full-throttle into forcing a response like, “god, there is no way I could spend more than two minutes with this person without screaming aimlessly in rage and frustration.”

In Darling, he’s enigmatic and absolutely without empathy. Both he and Dirk Bogarde play the male foils to Julie Christie’s incorrigible Diana Scott, but Harvey’s openly shallow work contrasts with Dirk Bogarde’s deeply shaded performance. Harvey offers no depth of emotion or feeling. It is obvious that his character is merely a shadowy projection. He makes no effort to humanize. He has built a blank façade. Harvey plays him as a compelling snake with no plans to warm up. Christie and Bogarde play people who cause varying degrees of harm through selfish pursuits, but the hook is that they do want to be happy, to be fulfilled, to be loved. Harvey’s Miles Brand shows no such desire—only a twisted, lightly-smiling desire to have control and power.

What is self-presentation if not an external action of innermost power and control? To dissect our own self-presentations is to ask questions: How do we see ourselves? How do we want to be seen? Every performer deals extensively in self-presentation. It is quite literally in the job description (I have now written “self-presentation” so many times it has lost all meaning and I am unsure how to pronounce it out loud anymore). But, few performers have ever made as much a concerted effort in pointing out the façade as Laurence Harvey did in his work. Is it damning him with undeserved praise to say that your loathing is what he expected? Yeah, his performances of being human register as somewhat cold, bleak, and out-of-step with any semblance of communal feeling. god knows, the cruel and cold male anti-hero concept is so dull and predictable (and always has been). I am not here to gas up that.

I am interested in the idea of that façade—the tightly controlled self-presentation—as a concealing act of self-protection.

“I’m a flamboyant character, an extrovert who doesn’t want to reveal his feelings.”

What happens when a flamboyant character (just look at his signature hairstyle—out there looking like a dandy from an earlier century), an extrovert who doesn’t want to reveal his true feelings, directs his first film?

You get The Ceremony (1963), a deeply idiosyncratic, stylized film that reveals many, many feelings. It is structured madness; structured chaos. The staging and shots are both uncluttered and extreme: purposefully drawing attention to themselves. Emotions are kept close inside with delicate facial expressions—and then exploded with full-body, uncontrolled movement.

I may be outing myself as a pretentious weirdo, but this is truly a favorite moment in cinema for me. There is a discomfort that comes from watching people let their bodies feel in outrageous waves.

This is a scene between Harvey, who has just escaped prison, his girlfriend Sarah Miles and younger brother Robert Walker Jr.