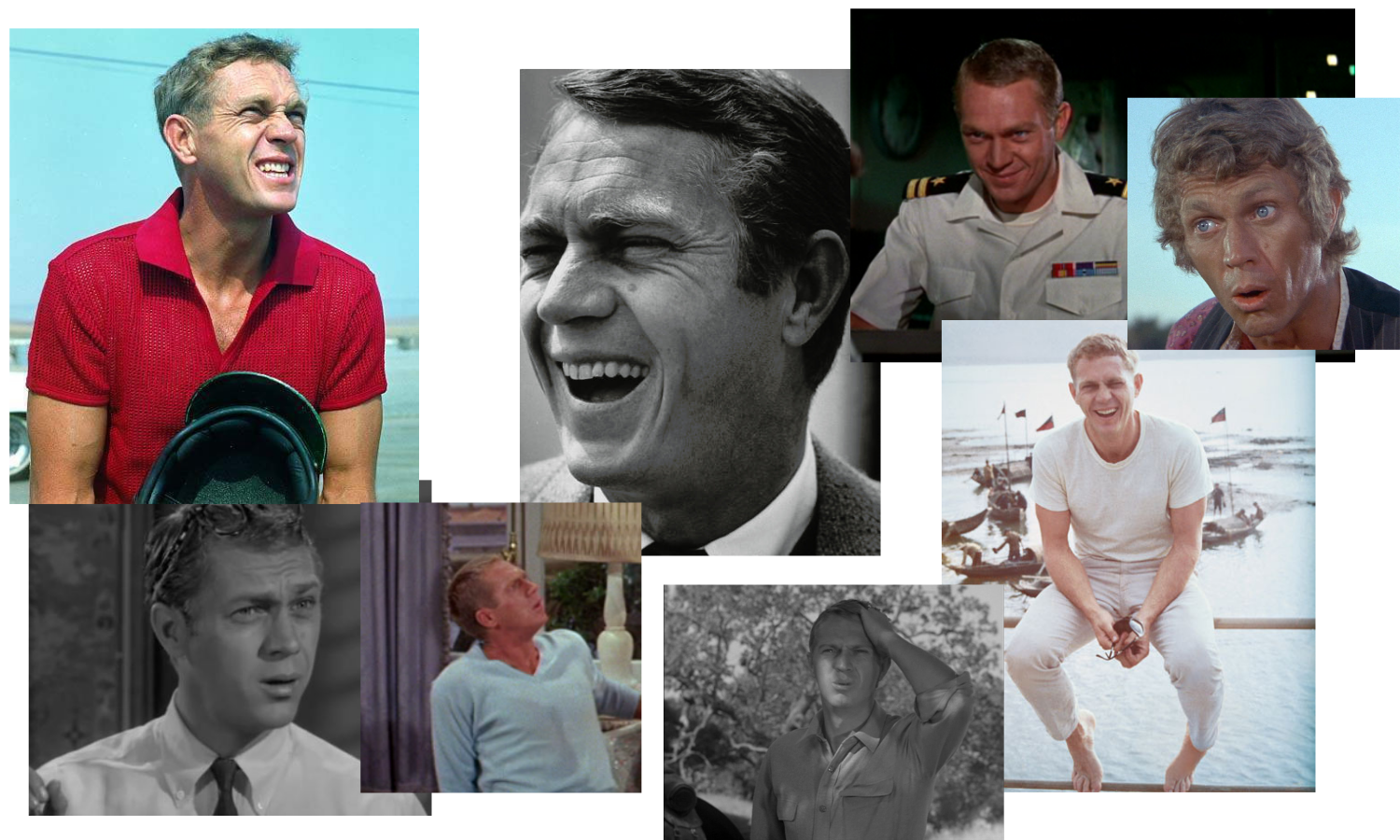

Steve McQueen, Cinema Goofball

Popular culture remembers Steve McQueen as the King of Cool, a paragon of stoic masculinity, a laconic man of few words and fewer emotions. But, what of the other side of Steve McQueen’s on-screen persona?

Popular culture remembers Steve McQueen as the King of Cool, a paragon of stoic masculinity, a laconic man of few words and fewer emotions. The remembered idea of him is two-dimensional, and–as a marketing scheme–highly successful: his name appears regularly in the lists of the most profitable dead celebrities. He is an image: stern, unflinching, immovable, untouchable. He doesn’t crack under any pressure, just like a Tag Heuer watch. He is “The Absolute Man” according to the vodka brand.

But, what of the other side of Steve McQueen’s on-screen persona? Not the vroom-vroom car chases and cool sunglasses and dialogue-free scripts. Not the decades of co-optive advertising. The other side: the much-maligned (but much-beloved-by-me), entirely uncontained, earnestly unsure total goofball.

I came to Steve McQueen early in life. He is my oldest brother’s favorite. Five years older than me, this brother always had a Steve McQueen movie playing, or a DVD lying about. My understanding of McQueen was formed first by the television series Wanted: Dead or Alive. And yes, he does play a cool loner bounty hunter traveling through the American settler west of the 1870s. But, his Josh Randall is also deeply connected to the people he meets along his travels, always getting involved, solving troubles, and occasionally forced into absolutely wacky shenanigans.

Burned into my memory, is an episode from the final season released in 1961, titled “Baa-Baa.” Josh Randall is sent in search of a lost pet sheep, there’s a singing chorus, montages of him chasing sheep over hills, and pratfall face grimace combinations not seen since the days of Cary Grant flying through Arsenic and Old Lace. That is my enduring image of Steve McQueen: flailing and just a little earnest.

I have written bits and pieces before about Steve McQueen’s depiction of masculinity. It fascinates me. It never seems to me to be the confident, unbreakable idea that endures from his most famous roles, but in actuality rather fractured and unsure, as if he was precariously holding himself together. Often the only outlet of emotions in these performances is violence. Once stardom took hold, there was an increasing unwillingness on-screen to divert from tightly-contained emotions and limited dialogue; almost as if to open himself up at all would be the end of his control.

This is a marked difference from some of the other enduring cool guys of the era, like Sidney Poitier, Toshiro Mifune, or James Garner. Their self-confidence felt entirely real and fully true to themselves in every kind of film or performance. James Garner was good pals with Steve McQueen, but also had this to say in The Garner Files, “He was a movie star, a poser who cultivated the image of a macho man. Steve wasn’t a bad guy; I think he was just insecure. … Deep down, he was just a wild kid. I think he thought of me as an older brother, and I guess I thought of him as a younger brother. A delinquent younger brother.” (Note: This is also what happens when you put two Aries together, I say as an Aries.)

That delinquent younger brother energy is a dominant theme in all of Steve McQueen’s “b-side” films: those films that do not comfortably fit into his steely iconography, and are left out of all the advertising and the cool montages.

Steve McQueen’s best performance comes in one of these films, Love with the Proper Stranger (1963). A romantic drama permeated with sweetness, it is McQueen’s softest role. His co-star Natalie Wood is glorious, confident, and self-assured even while her character is facing extraordinary fears and pressures. McQueen plays his character hesitant and awkward. He is a cool-cat jazz musician who trips over and mumbles his words and hunches and slouches his body. The finale of the film is the ultimate goofball gesture–and stunningly earnest.

Sometimes, Steve McQueen’s ventures into goofball territory are far less earnest. The Reivers (1969) is a film I would charitably describe as YIKES (but what a supporting cast! Rupert Crosse! The great Juano Hernández!). It is also a strange amalgamation of his competing film energies. There is the obsession with a car and emotions processed via violence (particularly directed at women), but there is also slapstick slipping in the mud and very big reaction faces. There is an internal battle for his performance soul warring throughout this film, and violent goofball is not really a comfortable spot to land.

Critical and public appraisal of McQueen’s ventures outside his narrow sphere has never been laudatory. Anything he did that came close to comedy has been thrown out in confusion with a note that it is “really not his thing.” Yet the problem with The Reivers is not the earnest comedy, but the elements of coldness and violence. Steve McQueen’s image sells luxurious watches under the promise that he doesn’t crack under pressure. Ice cold silence sells. Flailing limbs and high-pitched scrambling does not sell vodka--apparently!

Yes, the time has finally come to talk about The Honeymoon Machine (1961). This movie is bonkers, but with that impeccable internal logic that makes 1960s comedies run so smoothly in their own wild realities. It is also peak goofball McQueen. As a scheming sailor with a plan to game the roulette wheel in a Venice casino using a naval computer, he talks extraordinarily fast–often at a high-pitched squeak–and says more words than most of his other films all put together. He stumbles and trips and sways. He is a delight. He hated it.

He walked out of the first preview, and said he would never work with MGM again.

I think it is one of the most endearing McQueen performances. To watch him play a James Garner comedy role without James Garner levels of self-assurance is such a feat of sincere effort. He pulls it off too, because it is all McQueen. He may be playing a zany goofball, but the threat of violence feels ever-possible as he hops about manipulating everyone around him and talking about Nietzsche.

I love Steve McQueen’s on-screen work. 12-year-old me somewhat unconsciously attempted to model my stride on his after watching that long opening shot of him walking down the street in The Cincinnati Kid. His Vin in The Magnificent Seven is one of my favorite characters dear to my heart. His work as Sweater Detective in Bullitt is an aesthetic triumph. Wanted Dead or Alive fills my soul with joy (and I once wrote a piece about its fashion when I was 17). That episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents where he bet Peter Lorre his finger is a lesson in building tension in 25 minutes (I also love that episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents where he is a goofball Martian).

But, my understanding of Steve McQueen is not an image used to sell watches and vodka and cars. My Steve McQueen does sometimes crack under pressure. Sometimes, Steve McQueen was bold, violent, cold, angry, and harsh–causing pain that ripples. Sometimes, Steve McQueen was fractured, unsure, flailing, earnest–looking for a safe route to just be. Sincerity even in its tiniest measure is a hard-won human triumph! Long live the sincere goofball cinema of Steve McQueen! (Maybe don’t watch Soldier in the Rain though.)

originally published on The Classic Film Collective on 01/10/2022.