“I am not loveable”: Laurence Harvey and the performance of self-presentation

“Someone once asked me, ‘Why is it so many people hate you?’ and I said, ‘Do they? How super!’ I'm really quite pleased about it.”

“Someone once asked me, ‘Why is it so many people hate you?’ and I said, ‘Do they? How super! I’m really quite pleased about it.’”

Laurence Harvey fascinates me as an actor. As someone who had a relatively low-impact career (and certainly a short life, dying age 45), his acting continues to inspire a remarkable level of divisive responses among film people™. I have never quite been able to figure out exactly why, but it does seem rather instinctual. And, I am not usually one to wade into film people™ fights without a firm ground. (You can find teenage me timidly acknowledging, “people either love him or hate him,” in a review of The Ceremony.)

Nevertheless, my first instinctual response to Laurence Harvey was absolute delight. I was maybe 11 or 12, and I saw his episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. It has stayed firmly planted in my memory from the pure audaciousness. It is quite gruesome and unrepentant. Harvey plays the titular chicken farmer named Arthur, a charming but basically anti-social figure. He opens by telling the audience, smiling, “I am a murderer,” and then narrates his story. He murders his fiancé, disposes of her body in the chicken feed, raises chickens on that feed, and eventually sends some gift chickens to an investigating cop. The cop is so enamored with the taste, he asks for a list of feed ingredients. Arthur obliges, turning to the camera to state smoothly, “All but one. I left out that one special ingredient that really made it.” There is no justice and there are no consequences. (Hitchcock does offer a cheeky closing statement about the chickens growing to an enormous size and then probably killing and eating Arthur.)

I was transfixed. His character, and the story, were certainly misogynistic (a common characteristic across many Harvey roles), but there was something that intrigued me: the utterly manufactured façade of a self-image he projected.

Around the same time, I unintentionally saw his episode of Columbo (released in 1973, just a few months before his death): he played an emotionless chess freak murderer. In this, his character is once again set apart from natural and expected human warmth and emotion. I said, “Well, well, well. Tell me more.” (Let us not delve into my childhood psyche nurtured on too much Hitchcock and Columbo, and the Beatrix Potter story in which Tom Kitten is almost turned into a roly-poly pudding by giant rats.)

From then on, I kept an eye out for Laurence Harvey (carefully learning, with a couple missteps, to differentiate his name in a cast list from that of the viscerally terrifying and despicable presence of Lawrence Tierney). What he had onscreen, I could never quite articulate in my blogging youth, but I understood it and was drawn to it.

His screen persona was always openly enigmatic. He never tried to hide the fact that he was hiding—hiding his true self; his true feelings.

I have always connected his depiction of masculinity with that of Steve McQueen actually. McQueen is held up in popular memory as some icon of masculinity in the same limiting and distorted fashion that Marilyn Monroe is held up as an icon of femininity. Of course, they were actually both much more—and infinitely more complex—than the shallow containment allows (more on the glorious Monroe another time).

McQueen’s depiction of masculinity is far more complicated (and interesting) than his popular legacy would suggest, and far more aligned with Harvey than immediately obvious. Just as Harvey’s characters were often steeped in misogyny, McQueen’s were often violent—uncomfortably so. But also fractured. As if the confidence to live and express himself only worked in a narrow, tightly-controlled sphere, and he better not say too much or change his ways too much—or everything might disintegrate.

McQueen’s characters distracted us from their internalized self-doubt with an erected façade of coolness. He looked cool, and did performatively cool things, and never said too much—so how could we say he was anything but supremely confident himself? The cracks showed through though. (And his own pal James Garner called him an “insecure poseur” in real life, which is blatant Aries v. Aries violence but I’ll allow it.)

Why have I taken a detour through McQueen to talk about Harvey? I think they both spent their short careers depicting unsafe men: men who correspondingly never felt safe themselves to just be. McQueen covered his characters’ fractures with uncannily good film choices and an ability to project coolness. Harvey never even tried to play his characters as anything but self-loathing.

in his directorial debut The Ceremony (1963)

Laurence Harvey played roles of disliked men; broken men; loathsome men. To them, he gave the brutal honesty of self-doubt and self-loathing, often coupled with the inability to articulate these feelings—or even to fully understand the feelings for themselves.

His most famously remembered role today is probably Raymond Shaw in The Manchurian Candidate, but it is both typical and atypical Harvey. Typical, in the sense that his character is pretty universally disliked by all the other characters for much of the film, and also his emotions are tightly controlled, cold, and hardened. But, atypically, Raymond Shaw can articulate what he feels and understands about himself. He just has to get a little drunk first to say, “I’m not lovable. Some people are lovable, and some people are not loveable. I am not lovable.”

In his characters, he captured the angsty longing of James Dean, but without the openness; without the bare emotions; without the yearning reach toward other humans. As a teen Dean devotee, my innate alignment with Harvey’s work makes perfect sense to me. It appeals to the unconfident child with plans to show themselves to the world within a carefully chosen and constructed presentation.

It is a tricky business transposing screen persona over a fully-formed human person—and I really try to steer away from that in the general sense (*everyone ever trapped in a text thread while I discuss my favorite performers is now laughing heartily at this statement*). I do not know enough about the short life of Laurence Harvey to exhaustibly essay on it, but all due consideration to the death of the author, I can tell you why his screen persona—which often slotted in with his projected public persona—compels despite its carefully structured coldness.

His Joe Lampton in Room At the Top is fully concerned with the work of self-presentation. How can he react to the trauma and pain of life in a way that gives him strict control and power over his image to others? Of course, in this film, his image control is primarily routed through destructive and deeply misogynistic interactions with women. The self-loathing is strong here, and so is the childhood trauma. (He even steals a beat from James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause writhing-in-turmoil-with-a-toy-in-the-street performance near the end of the film.) The story concerns itself with the catastrophic ills of classism, and wealth’s casual habit of ignoring, dismissing, and then crushing to dust any would-be rebels in the system. Truly, an evergreen subject.

I recently rewatched this for the first time since my own angsty teens, and I was struck pretty much the same: adoration for the resolute clarity Simone Signoret gives her Alice, and a resigned *yikes* floating in the general direction of Harvey’s messy, messy Joe.

Joe is truly so very unlikeable in his attempts to beat his oppressors by becoming them. Harvey’s performance here works as a sort of thesis for his entire career of characters: resolutely individualistic, powered by self-loathing, somewhat irredeemable, yet still lit with a spark of uncanny energy. In every film, he was never anything less than calmly chaotic.

(his characters can oscillate between chaotic neutral and chaotic evil—but rarely even begin to whisper at a hint of chaotic good)

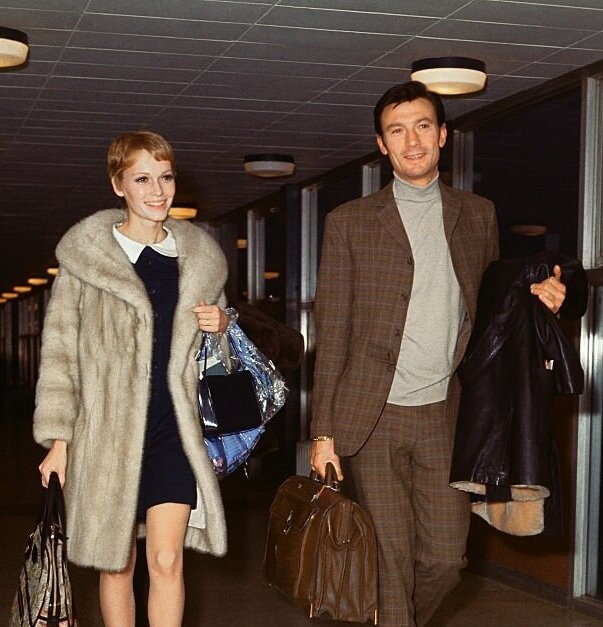

This is true even if you watch his early cinema work in England when he was more than once cast as some sort of charming rapscallion, life-of-the-party (perhaps more in line with his public self: a jet-setting, stylish Elizabeth Taylor BFF who managed to clash with seemingly every single introverted/subdued/serious actor he ever worked opposite). It is wild to see him play characters like the scamming talent agent in 1959’s Expresso Bongo (a fever dream of a film co-starring my very lively personal fav Sylvia Syms): a character who is likely intended to be seen as a troublemaker, but a fun one—yet in Harvey’s hands comes across as a somewhat unhinged menace.

This character type is a menace! It’s the archetype selfish conman who is always making plans to make money and treats the woman who loves him like trash while he’s bouncing off to another probably illegal scheme. Cinema is rife with them. Often, they’re a lot of fun to watch. Other actors use their own reserves of personal charm to smooth the rough edges; to make these loathsome men appealing. Instead, Laurence Harvey barrels full-throttle into forcing a response like, “god, there is no way I could spend more than two minutes with this person without screaming aimlessly in rage and frustration.”

In Darling, he’s enigmatic and absolutely without empathy. Both he and Dirk Bogarde play the male foils to Julie Christie’s incorrigible Diana Scott, but Harvey’s openly shallow work contrasts with Dirk Bogarde’s deeply shaded performance. Harvey offers no depth of emotion or feeling. It is obvious that his character is merely a shadowy projection. He makes no effort to humanize. He has built a blank façade. Harvey plays him as a compelling snake with no plans to warm up. Christie and Bogarde play people who cause varying degrees of harm through selfish pursuits, but the hook is that they do want to be happy, to be fulfilled, to be loved. Harvey’s Miles Brand shows no such desire—only a twisted, lightly-smiling desire to have control and power.

What is self-presentation if not an external action of innermost power and control? To dissect our own self-presentations is to ask questions: How do we see ourselves? How do we want to be seen? Every performer deals extensively in self-presentation. It is quite literally in the job description (I have now written “self-presentation” so many times it has lost all meaning and I am unsure how to pronounce it out loud anymore). But, few performers have ever made as much a concerted effort in pointing out the façade as Laurence Harvey did in his work. Is it damning him with undeserved praise to say that your loathing is what he expected? Yeah, his performances of being human register as somewhat cold, bleak, and out-of-step with any semblance of communal feeling. god knows, the cruel and cold male anti-hero concept is so dull and predictable (and always has been). I am not here to gas up that.

I am interested in the idea of that façade—the tightly controlled self-presentation—as a concealing act of self-protection.

“I’m a flamboyant character, an extrovert who doesn’t want to reveal his feelings.”

What happens when a flamboyant character (just look at his signature hairstyle—out there looking like a dandy from an earlier century), an extrovert who doesn’t want to reveal his true feelings, directs his first film?

You get The Ceremony (1963), a deeply idiosyncratic, stylized film that reveals many, many feelings. It is structured madness; structured chaos. The staging and shots are both uncluttered and extreme: purposefully drawing attention to themselves. Emotions are kept close inside with delicate facial expressions—and then exploded with full-body, uncontrolled movement.

I may be outing myself as a pretentious weirdo, but this is truly a favorite moment in cinema for me. There is a discomfort that comes from watching people let their bodies feel in outrageous waves.

This is a scene between Harvey, who has just escaped prison, his girlfriend Sarah Miles and younger brother Robert Walker Jr.

There is a line near the end of this clip that hits at one of Harvey’s themes in the film. He is specifically referring to the brutality of prison on a person’s spirit (side-note: abolition now!), when he talks of being reduced to the shadow a man.

“In there, I had time to think. I had never really taken the time to think before. What was I trying to prove? Where did it go wrong? And then I realized that it was too late. I was going to die knowing that I hadn’t lived. Do you understand what I’m trying to tell you? They try and reduce you into a shadow of a man. Your body begins to feel as if it doesn’t belong to you. Eating and eliminating. Detached. Your arms and legs begin to feel as if, as if they’ve been sewn on. Don’t think. Don’t feel. Flesh. Nothing. And you begin to believe it.”

While specifically a reference to the prison experience, it is also representative of some of the overarching themes (it can get a bit opaque and metaphorical in this film: just the way I like my pretentious cinema yum yum delicious) of power and control: who has control? how is power used? what makes a person human? how is each person’s humanity to be protected or destroyed?

To feel, as a person, like nothing more than a shadow—nothing more than flesh—is a grievous pain. Loss of autonomy is a grievous pain.

How do we see ourselves? How do we want to be seen? … How do we protect ourselves? How do we construct an image that cannot be breached? If we project coldness and inhumanity, do we save ourselves like the weakest prey puffing up before a predator? If we are sure we’re unlovable, can we say that being loveable is not the point?

Laurence Harvey’s canon of performances is filled with characters certain of their unlovability, and just as quick to present as unlovable in turn. Quick to project a self-image that prizes control and individual autonomy over relationship and community.

I think feeling loveable or not loveable is a universal human concern. It certainly looms quite dominantly when we’re young figuring out how to be. It has always explained to me why Laurence Harvey’s work compelled me. It said, "Build up your barriers! You’ll never be broken! (also you’ll never be happy!)”

Fortunately, I was also compelled in my formative years by two other male figures on my TV (look, I was homeschooled in the woods—I didn’t really see other adults except from my media): John Cassavetes and Mr. Rogers (honest to god, someday look for my comparison post about these two that’s been sitting as a draft since December).

Cassavetes: “And I don’t think a person can live without philosophy. That is, where can you love? What’s the important place where you can put that thing—’cause you can’t put it everywhere, you’d walk around, you gotta be a minister or a priest saying, ‘Yes, my son,’ or ‘Yes, my daughter, bless you.’ But people don’t live that way. They live with anger and hostility and problems and lack of money—with tremendous disappointments in their life. So what they need is a philosophy, what I think everybody needs, in a way, is to say, Where and how can I love, can I be in love so that I can live—so that I can live with some degree of peace? You know?

And I guess every picture we’ve ever done has been, in a way, to try and find some kind of philosophy for the characters in the film. And so that’s why I have a need for the characters to really analyze love, discuss it, kill it, destroy it, hurt each other, do all that stuff—in that war, in that word-polemic and picture-polemic of what life is.

And the rest of the stuff doesn’t really interest me. It may interest other people, but I have a one-track mind. That’s all I’m interested in, is love. And the lack of it. When it stops. And the pain that’s caused by loss or things taken away from us that we really need.”

Mr. Rogers: "Love is at the root of everything, all learning, all relationships, love or the lack of it."

I did not start writing this post intending to end up with Mr. Rogers at the finish, but I cannot say I am too surprised either. I did start writing this wanting to articulate why Laurence Harvey’s work meant something to me at my most impressionable ages. Truly what does a performer dead more than twenty years before I was born have to say through their film roles to a youth in the mid- to late-2000s if not, “Here is one way to live. You’re not gonna like it. But you’re gonna understand it anyway. Deeply understand it.” An extrovert who doesn't want to reveal their feelings? COULDN’T RELATE. I’M UNKNOWABLE! I’M UNKNOWABLE! (I scream into the void while absolutely oversharing, hence this very post on my own blog).

It is hard being human. It is hard to be human with other humans. It is hard to know yourself. It is hard to express yourself. What Laurence Harvey did with his work was to show the excruciating effort it takes to master an “unbreakable” self-presentation, and the open wound of making yourself invulnerable. The call of the void whispers that invulnerability is power, but the truth is in relationship and community with each other. <3

Please clap for the tremendous amount of self-restraint it took to not embed this clip of Daniel Tiger singing about being a mistake at the end of my post and thereby completing the parody of myself that is all this. Disgusting!

Also, this post is dedicated to Emmy—whose recent discovery of Laurence Harvey set me off on this journey down the old memory lane.

And, also to Kate—whose dedicated refusal to appreciate Laurence Harvey inspired many teenage Blogger/Twitter/Tumblr feuds on Friday nights.